|

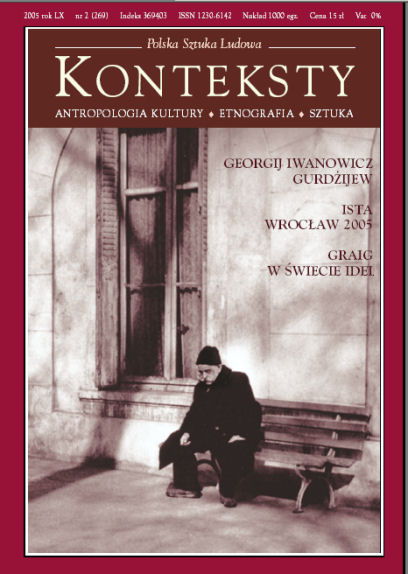

Special Section on G. I. Gurdjieff and

His Teaching Edited by Grzegorz Zió³kowski, Consulted with Tilo

Ulbricht, in Collaboration with James Moore

In his General Introduction Peter

Brook explains the motives for publishing in „Konteksty” a

section devoted to G. I. Gurdjieff and his teaching: „In November

2001, The Grotowski Centre in

Wroc³aw

organised a special seminar to enable Polish students and thinkers

to acquaint themselves with a vast subject – the teaching of

George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff. The considerable interest that the

three days of meetings and discussions aroused led to a powerful

wish to understand the subject more fully and more deeply. This

issue of ’Konteksty’ is a first attempt to respond to this

demand. It brings together the experiences of many who have devoted

a considerable part of their lives to following the Gurdjieff

teaching”. Gurdjieff was a „Greek-Armenian spiritual teacher who

remains an enigmatic figure and an increasingly influential force in

the contemporary landscape of new religious and psychological

teachings. […] He brought to the West a comprehensive model of

esoteric knowledge and left behind him a school embodying a specific

methodology for the development of consciousness”, Michel de

Salzmann writes in a biographical note included in the selection. [More

information can be found at the web-sites of The International

Association of Gurdjieff Foundations (www.iagf.org) and of Gurdjieff International Review (www.gurdjieff.org).]

The articles are grouped in six sections: Reception, Towards the Essence, Teaching, Belzeebub and

Movements, Gurdjieff –

the Man, and Bibliography. In the first

section, Grzegorz Zió³kowski writes about how little Gurdjieff

teaching is known in

Poland

. The situation is only now beginning to change – the first Polish

group supervised by a qualified teacher has been recently formed.

The author underlines that in

Poland

interest in Gurdjieff is mostly (but not exclusively) due to Jerzy

Grotowski for whom Gurdjieff constituted an important reference

point since the late 1970’s.

The second part is a collection of

texts based on speeches delivered at the „Towards the Essence”

conference organised by the Grotowski Centre in

Wroc³aw

(2001). For Peter Brook, James Moore, Laurence Rosenthal and Tilo

Ulbricht an encounter with Gurdjieff’s understanding formed a

central axis of their lives. In their capacities as a theatre and

film director (Brook), a writer (Moore), a musician and composer (Rosenthal),

and a scientist (Ulbricht) they present their own essential

perception of what this teaching means today. The third part, Teaching,

expresses the opinions of those who worked with Gurdjieff directly

and of the „second generation” of his pupils – as in the case

of James Moore and especially Jeanne de Salzmann; it is on her

shoulders that Gurdjieff placed responsibility for a continuation of

his work. Her guidance made it possible to develop and expand

Gurdjieff’s teaching and to draw together many of his pupils and

separate groups. She also supervised the translation and publication

of Gurdjieff’s written works. Over

a period of forty years, Jeanne de Salzmann worked tirelessly with

her pupils to preserve and transmit the exercises and dances

originally taught by Gurdjieff. Her First Initiation is a pitiless critique of those human beings who in

reality ‘are not what they believe to be.’ Only the acceptance

of this idea and observation without preconceptions can place women

on the path leading towards truth – Jeanne de Salzmann firmly

states. Thomas de Hartmann and P. D. Uspensky also belong to those

who met Gurdjieff (already in pre-revolutionary

Russia

) and collaborated with him. The former helped Gurdjieff to

translate his musical ideas into actual notes on paper. „De

Hartmann’s musical credentials were impeccable”, Rosenthal

writes. „He had studied at the Moscow Conservatory with the

well-known Taneyev, as had his contemporaries Rachmaninov and

Scriabin. He became not only Gurdjieff’s lifelong disciple, but

also his devoted collaborator, dedicating his deep musical

sensibilities to the realisation of Gurdjieff’s musical ideas”.

„Uspensky will be chiefly remembered for In Search of the Miraculous, published posthumously in 1949 and later in several

foreign languages under the title Fragments of an

Unknown Teaching. This work is by

far the most lucid account yet available of the teaching of G. I.

Gurdjieff, and it has been a principal cause of the growing

influence of Gurdjieff’s ideas”, John Pentland adds in a

biographical note on the Russian philosopher and thinker. The

section contains fragments of their principal books: De Hartmann’s

Our Life with Mr Gurdjieff, written with his wife, Olga, and Uspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous (a selected fragment focused on remembering oneself).

Texts by Michel de Salzmann and Henri Tracol, which come next in

this section, concentrate on different aspects of the teaching. De

Salzmann’s article: Seeing: The Endless Source of Freedom, which demonstrates the psychological background of

the author, puts emphasis on the quality of seeing: „As one begins to realize that

the fundamental aim is to become aware of the whole of oneself, then

the sacred quality of ’seeing’ becomes as important as what is

seen, and a balance begins to appear „. It should be highlighted

that from 1990 until his death in August 2001, Dr. de Salzmann

directed the network of Gurdjieff foundations, societies, and

institutes around the world. In his Remembering Oneself Henri Tracol,

President of the Gurdjieff Institute in

France

, evokes Gurdjieff’s lucid remark: „When you remember oneself,

what exactly is it that you remember?”. His text testifies to the

multifaceted questioning conducted by the author. In a chapter

entitled The Revelation in Question from the biography Gurdjieff: An Anatomy of a Myth James Moore pauses in his narrative on Gurdjieff’s life to present his

teaching as a multilevelled structure encompassing not only the

totality of human existence but also cosmology and a vision of the

entire universe. „Gurdjieff’s ideas and methods, in all their

breathtaking scope, are constellated around the idea of conscious

evolution”, accentuates the biographer. He concludes his

exhaustive account by declaring that „If this man cannot be

understood without his teaching, neither can the teaching be

understood without the man”. Gurdjieff’s teaching is transmitted

directly by his disciples and followers whose working tools include

the writings of their master and special gymnastics known as

Movements. A distinctive place among the books written by Gurdjieff

is reserved for Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, first published in English in 1950, i. e. a year

after Gurdjieff’s death. It is, as Michel de Salzmann notices, „an

unprecedent vast and panoramic view of man’s entire life on Earth

as seen by beings from a distant world. Through a cosmic allegory

and under the clock of discursive anecdotes and provocative

linguistic elaborations, it conveys the essentials of Gurdjieff’s

teaching”. The next section focuses on the word and the dance as

the vehicles of teaching, and includes texts by Henri Tracol (Thus Spake Beelzebub), who together with Jeanne de Salzmann worked on the French edition of Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, and by Joanna Haggarty (Some Aspects of Movements) and Pauline de Dampierre (The

Role of Movements) who taught the

sacred dances for many years. The section on Gurdjieff – the Man encompasses a

short comprehensive biographical text by Michel de Salzmann, written

for Mircea Eliade’s The Encyclopaedia of Religion, and three testimonies by Gurdjieff’s pupils from

different periods. In Boyhood with

Gurdjieff Fritz Peters, a boy when he met

Gurdjieff in Prieuré (south of

Paris

) during the 1920s, describes how strongly the master emphasized

incessant work on developing one’s self. Tcheslaw Tchechovitch’s

vivid evocation (The Dvadsatniki) of Constantinople in 1921, when the town teemed with refugees from the

Bolshevik revolution in

Russia

, shows the importance attached by Gurdjieff to the fact that those

around him were responsible human beings capable of overcoming

obstacles created by historical turmoil. Henriette Lannes in To Recognize a Master,

addressed to Gurdjieff’s pupils in 1957, on the eighth anniversary

of his death, evokes the impact of the master’s force which she

experienced in direct contact with him during the 1940s. True

teaching is validated by the quality of the teacher’s presence.

The selection ends with the editor’s bibliography of sources on

Gurdjieff in Polish and with text of Michel de Salzmann. This view

is further enhanced by Michel de Salzmann in his valuable guidelines

to those readers who can easily become lost in the abundance of

Gurdjieff literature. In the closing section devoted to written

sources De Salzmann stresses „the awakening power emanating from

his [Gurdjieff’s] presence” and points out that „All those who

approached him were marked indelibly by the experience”, adding

that „A definitive characteristic of a living teaching or

’way’ is that it cannot be found in any book”. He acknowledges

however that some books can be helpful as support while working on

one’s self, as well as that „testimony is a necessity”. His

sober remarks on the position of the written in understanding

Gurdjieff’s teaching can be revealing especially for those who

tend to confuse definitions with the living process of transmission.

14th Session of ISTA

The

Wroc³aw

session of the International School of Theater Anthropology (ISTA)

was held on 1-15 April 2005. The author of the project was Eugenio

Barba, director and head of the forty years old Odin Teatret

company, which every few years gathers in assorted places all over

the world a group of researchers dealing with the theatre in order

to jointly delve into the secrets of the art of acting. The prime

objective and premise of the functioning of ISTA is an extensive

theoretical and practical study of the manners of creating a

theatrical spectacle. Barba and his coworkers try to capture the

essence of the origin of that which may be described as the

phenomenon of theatrical qualities by applying scientific research

methods and so-called theatrical quests. The articles entitled „ISTA-

Wroc³aw

2005”

document the workshops, spectacles and lectures which comprised this

year’s session, enhanced with an attempt at a meta-reflection on

the meaning and premises of the Barba project in general.

Henryk Jurkowski

Craig in the World of Ideas

This summary of the book Œwiat Edwarda Gordona Craiga. Przyczynek do historii

idei (The World of Edward Gordon Craig. A

Contribution to the History of Ideas, in print) contains numerous

statements fully documented in the publication. The author embarked

upon a verification of many of the terms proposed by Craig, i. e.

the theatrical artist. Contrary to commonly held views, Craig did

not ascribe it to the director, but had in mind an authentic artist,

regardless whether the latter fulfilled the functions of the author

of the staging, the director or merely the stage designer. The

aversion expressed by Craig in relation to ready texts (e. g.

Shakespeare) was the outcome of the same premises – an „artist

of the theatre” should mould his output from the beginning to the

very end. Craig regarded the work performed by painters and graphic

artists, who decided about every detail, as exemplary, since it

involved selecting the material over which they subsequently

dominated. This approach proved to be a source of conflicts between

Craig and genuine actors, by no means complaisant. Naturally, he

appreciated outstanding actors, capable of transforming their

personality and body. Nonetheless, he envisaged the possibility of

creating a theatre which would apply assorted means of expression.

In 1905 he planned to open the International Uber-marionette Theatre,

with a seat in Dresden. The withdrawal of promoters compelled Craig

to focus on his conceptions by conducting a theatrical laboratory

and school in Florence. This was the period of the origin of his

first (unpublished) texts reflecting his interest in the theatre of

the ritual and the mystery play theatre. It was also at that time

that Craig presented his famous essay The Actor and

the Uber-marionette, issued in the

debuting periodical „The Mask”. This was not merely an attack

launched against the egoism and mediocrity of the art of acting, but

a manifesto in favour of the theatre of the ritual, inspired by

publications about the primeval religious rites of India. It was

also a demonstration in favour of the plastic arts theatre, which

placed the dynamic plastic metaphor in the forefront. Craig

transferred elements of this approach to his scenarios intended for

the puppet theatre. His reflections on the theatre (with a

predominance of objective elements over subjective ones) remained

influenced by Nietzsche, from whom he also probably fostered the

term „uber-marionette”. This was not the only inspiration! He

also borrowed animosity towards

realism and the social service of the

theatre, which is not to say that he did not support social

solidarism and even state institution benefits for the sake of...

the theatre. Neglected by the British theatrical milieu (throughout

his whole life Craig dreamed of being appointed director of an

English theatre) he valued all signs of recognition by fascist Italy,

Soviet Russia and even the victorious Third Reich in occupied Paris.

E. G. Craig was a complicated man, frequently inconsistent and naive;

at the same time, he remained a creator gifted with extraordinary

imagination, whose impact upon the twentieth-century European

theatre appears to be still insufficiently studied.

Henryk Jurkowski

The Art of Acting as an

Expression of Philosophical Dualism

In order to resolve an inquiry into

the character of theatrical mimesis the author examined all the „mimetic”

impulses which constitute either a certain context or the sources of

theatrical performance. The text starts with a reflection on the

conception proposed by Huizinga, i. e. to treat playing in general

as a source of human culture (homo ludens). This introduction is the reason for an analysis of children’s games,

whose point of departure is the activity of an infant who, deprived

of the mother’s breast, tries to dominate the objects which

replace it. In this manner there opens up a domain of psychological

analyses which lead to the notion of art according to Freud, Jung

and, predominantly, Nietzsche. All these authors perceived art as a

phenomenon of the objectivising „I” which, in the opinion of

Jung, produces myths and thus parallel worlds in a confirmation of

man’s inclination towards mimesis, mentioned already by Aristotle.

The existence of the phenomenon of mimesis is also attested by

contemporary anthropological research which, following the example

of James Frazer, acknowledges that mimesis possesses magical and

pragmatic functions. Michael Taussig drew attention to mimesis

conceived as a manner of existing with the Others, which implies the

multi-functional nature of emulation. Otherness possesses also a

specific internal dimension, disclosed in the use of persons

deformed mentally or physically as representatives of supernatural

forces. Such an attitude yielded the inveterate tradition of the

mythical jester, whose functions were subjected to assorted

transformations, and provided an example of the presence of mimesis

upon the borderline of reality and daily life. A distinct issue

involves the application of the mask as a likeness of the Other, to

be tamed and taught how to establish contact. In classical tragedy

the image of the Other persisted up to the time of pertinent

critical reflection, as in the case of every depleted myth. In the

theatre, the mask lost its sacral functions, making way for the

human actor, a fact which evoked a new situation. As a rule,

psychologists associate the act of creativity with echoing the

divine act of creation. The actor is deprived of such opportunities,

since he is not a substance that could exist beyond him. (The only

exception is the puppeteer who employs artificial substance). The

ensuing complicated situation demands that the actor define the

degree of his involvement in creating the depicted world. One could

say, therefore, that the actor (or the performer as such) enjoys an

extensive scale of possibilities defined by a chance for a dualistic

or monistic conception of the world. The former vision originates

from Plato, and claims that all that which we produce is a

reflection of the world of ideas. The actor’s role and his

impression of a character in a play correspond to this approach. The

monistic vision based on Fichte’s idealism, which assumes that the

source of all phenomena lies in the uniform spiritual „I”, makes

it possible for the actor to regard himself to be the gateway and

path towards becoming acquainted with the world. The dualistic

vision in the actor’s performance is confirmed by the metaphors

devised by Diderot, Antoine, Mikhail Chekhov and, naturally, Brecht.

The monistic vision springs from the deliberations of Artaud, the

„Living Theatre” and Grotowski. The whole issue, however,

becomes even more complicated in a situation when the initiator of

the conception of the actor’s performance is the director, and

especially when he treats the thespian as material for his own

visions (Kantor). In those cases, the dualistic visions harboured by

the director (I, the creator – they, the actors, my material

creation) does not have to concur with the stance of the performers

who find their own justification for the situation in which they

found themselves. These are the complications in the existence of

mimesis which one simply cannot foresee.

|