|

2006 (rok LX) |

Summaries: |

|

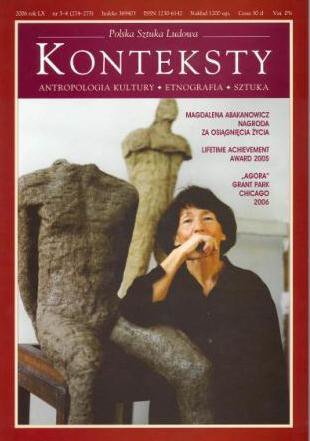

Zbigniew Benedyktowicz Why Abakanowicz? The answer to the

titular question (and the reason for the publication of this issue)

is obvious. In the autumn of 2005 Magdalena Abakanowicz received the

highest prize awarded to living sculptors by their milieu – the

highly prestigious International Sculpture Centre’s Lifetime

Achievement Award, presented in

The art of Magdalena Abakanowicz possesses its own profound

anthropological, symbolic and universal dimension. In this fashion,

the presented issue, thanks to the collected texts interpreting her

works and the statements made by the artist herself, has become a

significant part of a series of our most recent fascicles on the

anthropology of the image. It also situates itself in the very

centre of our anthropological discussion. Suffice to mention the

realizations of various Abakanowicz projects introduced into the

landscapes of Tuscany, Japan and Lithuania, and more broadly:

Europe, Asia, Australia, and America, to immediately ask about the

way in which this art, so deeply embedded in the individual

experiences of its author and so closely connected with local

culture and experiences, manages to produce such a response among

other cultural environments. If the essence of anthropology lies in

dialogue, then the works of Magdalena Abakanowicz fully deserve to

be described as anthropological art, not merely due to their

dialogical character. Their force also lies, as the authors of many

of the presented texts noted, in

”The validity of the universal view has been challenged and

in many ways stripped of its pre-eminence in recent decades.

Critical theory has deconstructed the universalizing impulse,

revealing it as generalizations of implicit colonialist arrogance.

Culturally specific, site specific, locally specific, community

specific: these are the terms that have come into use to

differentiate peoples, their cultures and their aesthetic

sensibilities. We have recoiled from the “universal” as a functional concept in our multicultural, pluralistic world. Yet some

artists – of which Abakanowicz figures among the very few of our

time – remind us that “universal” is not a passé notion

but an idea essential to the understanding of our humanity. In

revealing the aspects we share, the artist plays a critical role in

society. Through the singular example, Abakanowicz speaks of all in

the genus. A drawing of a flower is never of a particular plant,

just as each of the Faces (1981) in her earliest cycle of

major drawings are never portraits. Rather, the content of her

flowers is of indisputable universal relevance: birth and death,

pain and suffering, endurance and

The editors express their gratitude to all the authors of the

collected texts and the photographs, as well as the publishers whose

consent to include original versions of the texts and their

translations into Polish and English has greatly contributed to the

appearance of this issue. Special thanks go to Danuta Wróblewska

and Wies³awa Wierzchowska for their inspiration and initiative, and

to Ms Katarzyna Staniszewska and Artur Starewicz for their valuable

editorial cooperation.

|