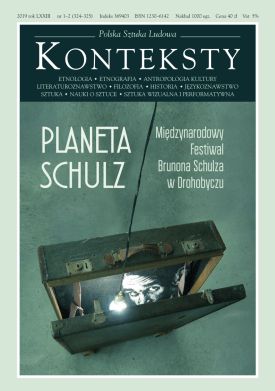

Issue 2019/1-2 (324-325) - Planet Schulz - VIII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz, Paweł Próchniak, Wiera Meniok, Grzegorz Józefczuk | Planet Schulz in the SchulzFest Cosmos. Conversation about the International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobycz | 6 |

| Władysław Panas | Lesson Given by Professor Arendt  | 19 |

This article deals with “Professor Arendt” – one of the protagonists of Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) by Bruno Schulz. Władysław Panas indicates that the Professor is not only a specially distinguished dramatis persona within the construction plan of the story but also an exceptional character in entire Schulzian prose, since he is the only mentioned by name whom Schulz transferred into his prose from the actual reality of Drohobycz. The first part of the article presents historical-biographical findings concerning Adolf Arendt – a teacher of drawing at the Drohobycz secondary school. Władysław Panas goes on to present an interpretation passage placing Professor Arendt against a wide backdrop of “nocturnal painting” and “graphic nocturnes”; by making use of of the strategy of “anagrammatical-hypergrammatical” analysis (inspired by notes by Ferdinand de Saussure on anagrams, anaphones, and hypergrams) he shows the structural relation between Arendt and Rembrandt and – more extensively – links the manner in which Schulz comprehended art and the vision of art present in his oeuvre. | ||

| Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak | Drohobycz, or the World  | 32 |

The article discusses and characterises the manner of perceiving Drohobycz inscribed in the works of Bruno Schulz. Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak recalls that the home town of the author of Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) plays a key role in his imaginarium, while the focus accepted by the artist is the reason why in his literary and visual art works Drohobycz appears as a “concrete place on Earth” (with recognisable topographic and architectural elements of reality) and, at the same time, as a space of creative imagination. It is precisely the latter – as the author of the article demonstrates - that processes the visible world and deprives it of reality, additionally placing upon its objective reality a filter of individualised sensitivity while, at the same time, reaching the real subsoil of visible reality, its invisible “bastion”. According to the interpretation proposed by the article the perception of Drohobycz suggested by Schulz possesses its imperceptible antecedents in the impact exerted by the spiritual and artistic aura of a town that co-created the culturally diverse milieu of painters connected with Drohobycz - widely portrayed by the author - and in various ways conceiving its iconographic “form of existence” (i.e. Leopolski, the Gottliebs, Lilien, Weingart, Stupnicki, and Lachowicz). | ||

| Igor Meniok | Brilliant Epoch, What Can I Say… Excerpts of Conversations and Notes  | 43 |

Excerpts of conversations and notes dedicated to Bruno Schulz by Ihor Meniok, co-founder of the International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych. | ||

| Paweł Próchniak | Bianka’s Villa. Short Guide to Drohobycz for the Friends of Władysław Panas - a Note | 45 |

| Władysław Panas | Bianka’s Villa  | 46 |

The article concerns “Bianka’s residence” – an important construction element of Wiosna (Spring), a story by Bruno Schulz and, simultaneously, one of the most prominent elements of this artist’s imaginarium. Władysław Panas analyses and interprets the “Bianka’s villa” motif, its structural and semiotic properties and inner-textual determinants, as well as those contexts belonging to it whose impact models to the greatest extent the semantic potential of the motif subjected to analysis. The crucial role in the research and reading strategy chosen by Panas is played by references to painting and - indirectly – to the reality of Drohobycz; the leitmotif of the presented deciphering is the multi-form presence in the story of “whiteness” (spanning from “whiteness” inscribed in the name: ”Bianka” to the iconic-chromatic value of “white” elements of the depicted world in Wiosna). | ||

| Paweł Próchniak | Warp. Sketch to a Portrait of Władysław Panas  | 53 |

An outline of a portrait of Professor Władysław Panas – scholar and man of letters. His accomplishments as one of the most outstanding Polish semioticians and an observant and thorough interpreter expanded the potential inherent in the structural-semiotic method. Furthermore, Panas’ writings accommodate intuition, maintaining that in the humanities style (the very manner of conducting a discourse) possesses not only rhetorical merit, but is also a prominent research instrument, which aligns itself with the cognitive force of the metaphor and thus allows cognizant thought to operate on the borderline between art and science. Panas is a sophisticated theoretician of literature and a brilliant interpreter of literary works. At the same time, he deals with the semiotics of the temporal-spatial dimension of culture. This is the reason why he reads literary texts in their complex links with the texts of space and its symbolic tissue. This is true in particular of his approach to the oeuvre of Bruno Schulz and Józef Czechowicz (to whom he devoted a major part of his considerations) and the hometowns of both authors: Drohobycz and Lublin. The author of the presented article lists Panas’ most important research achievements and writings, indicating that the cognitive dimension of his work is closely connected with an existential counterpart, while the cognitive ambition out which this accomplishment arises is also that of cognizant imagination and its striving towards a restitution of sense inscribed into human reality and, more widely, into the world and its existence. | ||

| Wiera Meniok, Igor Meniok | Will Not Allow Us to Lose Our Way in Schulzian Space  | 57 |

Recollection of Professor Władysław Panas. | ||

| Leonid Golberg | Memory and Gratitude  | 59 |

Recollection of Professor Władysław Panas. | ||

| VIII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych, 2018 | ||

| Adam Zagajewski | Towards Drohobycz  | 61 |

Tragically, Bruno Schulz died before he could draw artistic conclusions from the cruel hunt known to history – and whose victim he became. On the other hand, it is a good thing that his pre-catastrophe writings allow us to better comprehend just how radical was this tragedy. The visual material at present at our disposal – the food for our imagination and school aids, which could make it easier for us to understand the nature of life in shtetls scattered across provincial Poland – is extremely modest. As a rule it involves only black-and-white photographs showing poverty, emaciated horses pulling primitive carts, old women wrapped in scarves and shawls, humble and, as a rule, wooden houses or cottages, geese condemned to death and carried to markets, barefoot children running and playing in sand or mud, and old men resting on benches. Sometimes, there are also brief snatches of a documentary film. Was Drohobycz too the site of geese, scraggy horses, and carts? Probably. Did Drohobycz differ from other small towns? Perhaps not. Schulz’s prose does not transpire exclusively in Drohobycz but in all the places of residence of more and less pious Jews. This is by no means a black-and-white prose. | ||

| Sjón | Cinnamon with Ice. Adventures of Bruno Schulz in a Land Where a Day Is Four Hours Long  | 64 |

Light. This is the first word that comes to my mind whenever I reflect on Bruno Schulz. The word itself, its literary connotations and, at the same time, a natural phenomenon. An endless games played by different lights, starting with the golden days of late summer, the obscurity of attics and closed sideboards, the darkness concealed within an abandoned woman’s glove, and glimmering glass jars full of condiments – endless variants of words describing the entire spectrum of those states. In addition, there is the manner in which they become intensified or splintered by fiery sparks and cool shadows. This is the first thing I recall when my mind becomes connected with an area that stores the earliest and, at the same time, the most recent recollections of reading Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) and Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą (The Hourglass Sanatorium). | ||

| Bruno Schulz: Philosophy, Poetics and Other Perspectives of a Place | ||

| Piotr Śliwiński | Phantom Calligraphies: Schulz – Wat – Różewicz  | 68 |

The article concerns the application of the ”calligraphy” motif in the writings of Bruno Schulz, Aleksander Wat, and Tadeusz Różewicz. All three men of letters – belonging to “the nation chosen for the Holocaust” – share the secondary, the incidental, and the indigenous, which, however, do not anchor and obliterate the awareness of a deprivation of values offering support. At the same time, the authors in question belong to the “category of observant participants”, who due to their presence in time and place open up spaces of stirring and terrifying conjectures, although, at the same time, they are witnesses and victims of the grim literal quality of history. All these features are concentrated in the motif of calligraphy (the calligraphy quality, line, contour, outline, relief, shadow), which appears in important fragments of works by Schulz, Wat, and Różewicz. The particular prominence of “calligraphy” is indicated by Bruno Schulz’s Wiosna (Spring). Here, the concept refers to the expressiveness of the image and, simultaneously, to the uncertain ontology of the presented phenomenon. Calligraphic perception, therefore, strives towards capturing the distinctive contour and the mysterious essence of things – it is a description of existence based on metaphysical intuition. The author of the article is interested in the copresence of the calligraphy quality and illegibility (elusiveness, undesirability) as well as in calligraphy taming the spontaneity of writing, imposing a form, granting shape and, at the same time, indicating that writing always possesses some sort of a dark side, inaccessible to the eye. In this manner, calligraphy accentuates the incompleteness of cognition and the inexpressibility of experience, while simultaneously suggesting that the calligraphic form – by storing within the intimacy of the act of writing – indicates the presence of something that guides the hand engaged in writing (this, in turn, implies the possibility of the existence of a metaphysical source and evokes that the search for truth does not have to be treated as a futile effort). Śliwiński interpreted selected fragments of prose by Schulz and poetry by Różewicz and Wat, and indicated in close-ups that the calligraphic image of works by these authors is not merely a con tour of experience and cognition, and does not only touch directly “the night of existence”, but also enters into a relation with the problem of the presentation and creation of the world prior to and after a catastrophe (including: before and after the Holocaust); the passage (outlined in the article) concerning the intuition and strategy of three writers resorting to calligraphy runs a course spanning from the premonition that “the blood of mystery”, whose “dark fluid” originates from the “night of existence”, circulates in an artwork (Schulz), followed by the pursuit of literature, which consists of listening closely to the silent “night of the world and experience” (Wat), all the way to the writer’s recognition of the paradoxical void inhabited by death (Różewicz). A comparison of fragments of Schulzian prose and poems by Wat and Różewicz thus serves not exclusively a demonstration of the vitality of certain motifs (writing, contour, chiaroscuro), but, first and foremost, is to disclose the process of filling the “other side” with increasingly dark content: unconceivable sense (Schulz), endless pain (Wat), and omnipresent death (Różewicz). | ||

| Jerzy Jarzębski | Power and Revolt  | 75 |

An essay dedicated to the motifs of power, obedience, and rebellion against the latter in the prose of Bruno Schulz – from the Father character and that of God to political authority from the period in which Schulz wrote his texts. | ||

| Stanisław Rosiek | Clichés of Phantasms. Introduction to Reading “Xięga Bałwochwalcza”  | 80 |

Was Xięga bałwochwalcza (Idolatry Book) at the onset of the artistic path pursued by Bruno Schulz? The small number of the artist’s preserved works from the first stage of his œuvre makes it impossible to solve this question. Even if Xięga bałwochwalcza does not include everything it certainly contains much of that, which we come across (or not) later in a developed or transformed form, albeit at times also deeply concealed and disguised in his entire œuvre, including literary works. It is thus necessary to start with Xięga bałwochwalcza. There is no better road leading to Schulz’s literary world. The problem lies in the fact that Xięga bałwochwalcza is not an orderly work. Nor is it completely present in the domain of culture. A copy encompassing all works does not exist (never existed?). Schulz treated on-the-spot configurations totalling more or less twenty graphic works selected from amongst 29, which upon each occasion he placed in a portfolio specially prepared for this purpose. Xięga bałwochwalcza is a work in motion – scintillating, with an ultimately undetermined configuration and unknown composition. While working on Xięga Schulz – no one knows why and in what way – resorted to the cliché-verre graphic technique that does not involve paint and a printing press but light, which by penetrating a negative manually prepared on a glass pane, draws on positive paper traces initially invisible and then chemically developed. With metaphorical exaggeration one might say that this is the black light of the phantasm. Xięga bałwochwalcza is a collection of curious photographs of the artist’s gloomy interior and his concealed desires – private phantasms. His work, however, does not end at that exact moment. Sometimes the artist retouched the copies. Such secondary operations correct the visual presentation of the phantasm in time, when it suspends (or ultimately loses) its power. Holding the retouching instruments Schultz often entered the sphere of presented appearances. Now, creative activities, whose object was the negative, recommence on the positive print. The extent to which the changes performed at this stage could take place is demonstrated by a Cracow copy of a graphic work: Procession, in which the central figure of the adored female changes her appearance. | ||

| Józef Olejniczak | The Schulz Heritage  | 88 |

An attempt at pondering the phenomenon of the reception of the Bruno Schulz œuvre and, at the same time, of the vitality of Schulzian tradition in contemporary culture. While deliberating on the “Schulz heritage” the author indicates the prime features of Schulz’s writings, which ensure that his stories are constantly interpreted anew while researchers, critics, and simply readers (whom the author of the presented sketch calls “The Schulz Order”) discover ever new meanings and senses rendered topical. Among the most important features of this œuvre Józef Olejniczak lists the following: 1. An original manner of moulding the narrative oscillating between myth and contemporary plot; 2. Shaping the auteur subject on the borderline between autobiography and self-portrait; 3. The originality of the depicted world, the representation of the real/oneiric/mythical/ simulacral and its dynamic disclosed in the metamorphoses of characters and protagonists; 4. The presence of psychoanalytical problems: the Father, the Oedipus complex – the conscious / subconscious / unconscious; 5. The presence of problems associated with sexuality (the body – Adela and Bianka – bliss – suffering – alienation – death); 6. Multiculturalism (Polish – Jewish – Christian – Greek – Central European – Modernist); 7. The presence of the motif of the town-labyrinth; 8. Intertextuality comprehended also as relocation between linguistic and visual-art texts; 9. The presence of a theme referring to Old Testament tradition and associated with the writ, the Book, the first word, genesis, and the “mythisation of reality”. The author recalls the person of Bruno Schulz, demonstrates the latter’s topicality outlined in Dziennik by Witold Gombrowicz, and notices the concurrence of the images of Western Galicia from Schulz’s stories with those in prose by Joseph Roth. At the end of the sketch he suggests interpretations of poems and essays by the contemporary Ukrainian author Serhiy Zhadan as homage paid to the vision of Drohobycz (Drohobych) created by Schulz. | ||

| Paweł Próchniak | Fold, Tuck. On One of the Interweaves of Motifs in Manekiny by Bruno Schulz  | 95 |

The bird motif in Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) resounds the strongest – in assorted manners and according to different rights – in three stories: Ptaki (Birds), Wichura (Gale), and Noc wielkiego sezonu (The Night of the Great Season). A reflection of the “bird event” plays an essential role also in the cycle created by Manekiny (Mannequins) and three parts of Traktat o manekinach (The Treatise on Mannequins), where – similarly as in other links of this volume – the bird motif is harmonized with that of the nocturne. The author of the presented text is interested in this harmony and the “principle of the negative” governing it and based on an interference of reverse supplements due to which the narrative “tucks” and “folds” are arranged in a palette – providing much food for thought – of the stirrings of metaphysically attuned imagination. | ||

| Dariusz Czaja | Schulz’s Mytho-logique. A Reconnaissance  | 100 |

Much has been written about the myth in Schulz’s œuvre. The affiliations of his conception of the myth and the proposals of twentieth-century theoreticians of myths have disclosed Schulz’s creative borrowings from sophists (Karl Kerényi) and men of letters (Thomas Mann). The author proposes deciphering Schulz’s visionary essay: Mityzacja rzeczywistości (The Mythisation of Reality) from two insufficiently defined perspectives: the relation between the myth and science as well as the future of the myth. Seen within this context the Schulz text proves to be completely contemporary and precedes by several decades the diagnoses of the philosophy of science (Enzensberger) and hermeneutics (Gadamer). | ||

| Jacek Maria Kurczewski | Schulzian Sociology – a Sketch of the Problem  | 108 |

This article undertakes a reconstruction of Schulz’s literary œuvre as the sociology of the Umwelt, the world surrounding it. The author claims that the artistic work performed by Schulz is at the same time sociological, i.e. a departure from the egocentrically experienced world for the sake of a world of intersubjectivity, i.e. the Town generated by Schulz’s experience of Drohobycz. This is by no means a socio-graphic description of Drohobycz, but a theory of the Town proposed by the narrator. Starting with the child’s room it encompasses the whole family Home-Shop together with the structure of family and servant dependencies defined by gender and age; subsequently, it involves the entire Town and, finally, the World associated with the outer Universe – the source of war and revolution spreading to the Town. Earlier, the World introduced the Town to the industrial revolution, which shattered the traditional trade ethos up to the dominating in the Town. The Town’s social life possesses its institutions, e.g. the Barbershop, the Cinema, the ladies Café, and the men’s Restaurant, which are the object of Schulz’s sociological micro-studies. It also contains various social loops, such as a fire brigade or the upper stratum of the Jewish tradesmen, but also assorted varieties of the crowd: the throng engaged in trading, the crowd of passers-by, or the revolutionary multitude. Social life is not a steady state because together with its natural environment it is subjected to the constant oscillation of the seasons of the year and the time of day and night. Schulzian egocentric sociology lacks society and involves the world of life and social life, which oscillates and artistically dominates in different rhythms but in accordance with Schulz’s subjective reality. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | Hah! Schulz? Place of Invention and Fuss with the Myth of a Place  | 117 |

The author stressed the existence of a legion of the Bruno Schulz character, whose stories give rise to the incessant curiosity of the theoreticians and historians of literature, with the latter presenting increasingly new interpretations of Schulz’s prose. The same is true of the writer’s biography, brimming with unclear moments. Gregory Józefczuk suggests that this multitude of interpretations, which testifies to the success and global popularity of Schulz, simultaneously influences the first experience of reading his prose and contact with it. Direct contact with the author’s linguistic imagination is disturbed by interpretations, with the biographical context of the Schulzian oeuvre being most susceptible to interpretation corrections and surmises. | ||

| Marek Tomaszewski | Bruno Schulz and the Geography of the Artistic Milieus of His Epoch. The Relation between the Place and Visual-art Activity Along the Eastern Borders of Europe  | 123 |

Did Schulz belong to a certain milieu, which concentrated the strivings of a group of artists working in a certain delineated geographical region? Portraits and self-portraits, illustrations to own stories, drawn sketches to unwritten prose, notes marked with erotica – those vividly differentiated formulas of artistic expression do not facilitate the research pursued by critics. Apparently, Schulz found it less of an effort to create visual-art works than to write. Nonetheless, this does not signify universal triumph and recognition; to the last days of his creative life Schulz, already an acknowledged man of letters, cherished unfulfilled hope for artistic success. Upon numerous occasions he expressed regret that he was incapable of mastering the art of woodcutting. As a graphic artist, illustrator, and draughtsman he concentrated on his world of the imagination and tended to avoid participating in programme disputes. In the course of several decades there appeared numerous publications analysing Bruno Schulz’s attitude towards art. In Poland interesting interpretations were offered by Jerzy Ficowski, Małgorzata Kitowska-łysiak, Krystyna Kulig-Janarek, and Irena Kossowska and in France by Serge Fauchereau. In this essay Marek Tomaszewski wishes to delve into the character of Bruno Schulz’s artistic debut as a graphic artist and draughtsman within the range of a local milieu typical for ethnic and cultural differentiation, as well as to follow his artistic path and wide gamut of social life connections. It is a known fact that Schulz’s artistic Modernism assumed form, i.a. under the impact of East European Jewish avant-gardes, which could have won the recognition of the debuting artist from Drohobycz. Who were the artists with whom Bruno Schulz exhibited his graphic artworks? What is the relation between this period of strenuous although much censored (in the case of Schulz) artistic activity and reviews written by the author of Sklepy cynamonowe in “Przegląd Podkarpacia” at the end of the 1930s, dealing with such artists as Ephraim Moses Lilien or Feliks Lachowicz? Who belonged to the closest group of Schulz’s artist friends? In this essay Marek Tomaszewski attempts to resolve precisely those and other questions. | ||

| Tomasz Bocheński | Metamorphosis as Interpreted by Schulz  | 129 |

The author of this essay analyses fundamental categories applied by Schulz: humour, metamorphosis, and matter conceived as forms of the dialogue, which comprises a dispute involving two ways of seeing matter: contemporary and regressive. Modernity, which aims at describing, naming, and evaluating things, tackles regress striving towards life, creativity, and the poetic nature of matter. Ironically and with perverse humour Schulz evoked voices assessing the creative undertakings of the Father in order to defend his own right to a creative transformation of things, to metamorphosis. Tomasz Bocheński interpreted the latter in Schulz’s œuvre as the metonymy of creativity and creative existence. | ||

| Lajos Pálfalvi | Poetics of a Small Town  | 138 |

In her monograph Agnes Klára Papp analysed Hungarian prose from the last century by resorting to the methods of geopoetics and placing strong emphasis on the theme of the province. Hungarian classics created a sui generis anti-myth of a small town conceived as the reverse of the experiences of the modern subject. The extraordinary character of the small town created by Schulz could be captured by confronting this world with realistic depictions. Apparently, Schulz’s Drohobycz is not at all provincial and in certain respects even resembles to the eternal city described by Yuri Lotman. The protagonists are already prepared for the coming of the Messiah and almost welcome Him. Moreover, the centre of the town comprises a certain “metaphysical junction”, with the lower world joining the upper one. This Drohobycz crosses the boundaries of provincial existence not solely in an esoteric fashion. By way of example, images of modernisation and changes of manners and morals in Ulica Krokodyli (Street of Crocodiles) still provide material for sociological interpretation. | ||

| Stanley Bill | Schulz’s Weeds  | 142 |

The world created by Bruno Schulz is full of plants: in his stories we frequently come across descriptions of assorted vegetation and extensive metaphorics based on botanical comparisons. Already the great ingenuity of Schulzian language suggests the lushness of plants. At the same time, Schulz described the origin and structure of history and myths with the intermediary of the same metaphorics. According to this conception his stories constitute precisely regrowth, regeneration, “new greenery” or “green coating” rejuvenating the branches of old myths. Schulz’s imagination is profoundly botanical. The author of this essay concentrates on a specific variety of omnipresent plants, i.e. weeds. Weeds – or wild growing plants in a wider sense – play a specially important part in the world of Schulz’s stories by representing the unusual “fertility” of vegetation and mindless life in its purest form. Within the range of the town, where the plot of the stories as a rule takes place, this impersonal form of life comprises the decisive majority of the described plants, both literally and metaphorically. Moreover, in the world depicted by Schulz weeds possess a specifically significant ontological status because they grow along an uncertain borderline between culture and Nature. On the one hand, weeds do not belong to the world of human forms albeit, on the other hand, they are not part of wild Nature. In Schulz’s stories – just as in extra-literary reality – weeds blossom and develop best of all in courtyards and garden flowerbeds, on walls and roofs, and in streets and roadside ditches. They need people and their activity. Weeds are not only opponents of created forms of human culture but to a certain degree they are its products. In this sense they are archetypical beings of Schulz’s borderline between wild matter and human form. | ||

| Jurko Prochaśko | Sphinx in a Labyrinth. Walter Benjamin and Bruno Schulz in Search of a Lost Childhood  | 147 |

The vividly diverse works by two outstanding twentieth-century European men of letters: Bruno Schulz – Polish artist and author of prose from Drohobycz, and Walter Benjamin – German philosopher, essayist, resident of Berlin and a cosmopolitan, contain numerous tangible similarities. Those “selected affiliations” are discernible primarily in reference to childhood recollections. In the case of Schulz the topos in question, which in the literature of high modernism achieved the attributes of a separate convention, revealed itself most clearly in Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) and in the case of Benjamin – in Berliner Kindheit um 1900. A comparison of these works from this vantage point is the prime interest of the presented essay. | ||

| Dariusz Wojakowski | The Construction of Urban Space in „Sklepy cynamonowe” by Bruno Schulz  | 153 |

The article intends to characterise the manner in which urban space is constructed in The Cinnamon Shops. The applied method of analysis refers to general premises of studying the unique cultural contents proposed by Clifford Geertz. The concepts accepted as points of departure for analysis include those of space formulated in humanistic geography (Yi Fu Tuan) and anthropology (Marc Augé), perceived as spatiality, place, and non-place. Analysis indicates that the Schulzian construction of town space consists of the creation of an anti-archetype of the place, which originates from the fact that the author treated features typical for space as its modality. Schulz also indicated the multi-strata nature of space built by the rules of the visual nature and changeability of perspective as well as its multi-dimensional character – the result of a modal description of the town’s features. | ||

| Żaneta Nalewajk | The Place of Nature, the Nature of Place – Schulz and Goethe  | 161 |

The main goal of the article is to present the parallels between Goethe’s idea of plant and animal morphologies presented in his works (i.a.:Vorarbeiten zur Morphologie) and poems (such as Metamorphosis of plants, Metamorphosis of animals or Epirrhema) and Schulz’s conception of matter formulated in The treaty on mannequins and other stories from the volume The Cinnamon Shops and the text stylized on the letter entitled To Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. The authoress also analyzes a paradoxical way of description specific not only to the matter created by Schulz but also to Goethe’s nature shown by Georg Christoph Tobler in the aphoristic poem entitled Nature written after his many conversations with the author of Faust. | ||

| Jurko Prochaśko | Why Vogel? | 167 |

| Debora Vogel | Streets and Sky  | 168 |

Fragment from the volume: Akacje kwitną by Debora Vogel (1933) together with comments by the translators of her texts into Ukrainian and Japanese. | ||

| Ariko Kato | Translating Acacias Blooming by Debora Vogel into Japanese: Temptations and Hardships  | 169 |

This paper outlines the significance of Debora Vogel’s prose in 20th century modernist literature. Additionally, referring to my own experience of translating Vogel’s Acacias Blooming (published in Yiddish in 1935 and Polish in 1936) from Polish and other works from Yiddish, this study explores the characteristics of Vogel’s prose through her original concept of the “montage” as a literary genre, as well as the similarities in literary and artistic concerns between Vogel and Bruno Schulz. First, this study suggests that Debora Vogel, a Yiddish modernist writer who was rediscovered in the mid-2000s and who contributed to modernist Yiddish magazines published in the US, is a key figure in the reevaluation of the modernist movements of Central and Eastern Europe. Vogel’s choice of Yiddish, a language of diaspora that was not her native tongue, enabled her, living in Lviv, the “periphery” of modernist literature and art, to join the forefront of modernist literature flourishing in major cities like Paris, New York or Berlin. Second, by describing the characteristics of Vogel’s prose and her concept of “montage,” this paper explains the difficulty of translating her prose into Japanese (for example, her frequent use of conjunctions like “and” and “but”). Third, this paper identifies similarities in the literary and artistic concerns of Vogel and Schulz as well as their different approaches: first, they attempted to blur the traditional boundary between visual art and literature, and second, they objected to the poetic language proposed by Tadeusz Peiper. Finally, this paper summarizes the current trend in the study of Polish interwar literature in which interwar Polish writers like Vogel, Schulz, or Bruno Jasieński, who were bilingual or multilingual, have become key figures in the present day reevaluation of the modernist maps of the 20th century. Their activities reached beyond the boundaries of language and country, therefore, by searching for the materials written by or on these writers in languages other than Polish, we can discover new networks and extensions of European modernism. | ||

| Ariko Kato | Stamps, Map, and Ruler. The Bruno Schulz Postcolonial Vision | 175 |

| Hana Nela Palková | The Schulzian Księga as a Mysterious Place  | 179 |

This article is based on a thesis maintaining that the text in such initiation works as Schulz’s Księga is conceived as a place containing a holy esoteric secret. In accordance with the French theory of the novel the author of this article conducts upon the example of Schulz’s stories an analysis of the term: mise en abyme, i.e. a book perceived as specific space created within the range of the literary text. Two varieties are distinguished: the self-reflective text, which is its own theme (the topos of the text-town or the book-labyrinth), and narration, within whose range the text revolves around its axis (the cyclical structure of Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą). Finally, Hana Nela Palková refers also to the idea of the Schulzian Księga / Book as the Talmud. | ||

| Agnieszka Giszterowicz | Paths of Familiarity with Schulz’s Accountancy  | 182 |

An article dedicated to accountancy present in the works of Bruno Schulz – the sort of accounting described by J.W. Goethe as “one of the most beautiful discoveries of the human spirit”. A study of Schulzian dylogy and works by the interpreters of his œuvre, an analysis of concepts borrowed from economic sciences and accountancy, and an analysis of the accomplishments of theoreticians within the range of this science create a set of instruments that make it possible to resolve the question concerning the impact exerted by accounting on the protagonists of the Schulzian dylogy. Can accountancy be perceived as a sui generis causal power thanks to which (instead of: despite which) Jakub / Jacob underwent spiritual experiences? In order to grant accountancy the function of a portal leading to spirituality it is necessary to alter the perspective of perceiving this science and to create for it a place in metaphysical space, art, Goethean polarity, etc. The most recent achievements of researchers representing this particular domain create such an opportunity. | ||

| Henryk Siewierski | The Motherland as Bruno Schulz’s “Fragment of a Larger Whole”  | 194 |

“Fragment of a larger whole” is a footnote, which Schulz placed at the very beginning of his story: Ojczyzna, published in the 59th issue of “Sygnały” (1938). Although nothing appears to indicate that this footnote was to refer to the very conceit of the motherland its possible ambiguity makes it possible to understand the titular concept as part of a larger and more complex whole. With total premeditation the author referred the word: “homeland”, which the Schulzian protagonist does not use to describe his native land, to the town of exile situated on this antipode. Since it was exactly in this work that Schulz constructed a narration whose very title indicates an intention to write about the motherland and to render the latter a prime theme, as has never been the case in his works, and although already its first reading might astonish and not correspond to the reader’s earlier moulded visions, it is worth listening in good faith to what the narrator and, simultaneously, the protagonist has to say and to ponder which “larger whole” could become the motherland in this story, one of Schulz’s last. | ||

| Katarzyna Warska | Schulz as Seen by His Male and Female Pupils. Putting the Archive of Reminiscences in Order – a Summary  | 197 |

The author of this article presented her plan aimed at introducing order into the scattered archive of recollections about Bruno Schulz pursued upon various occasions by his pupils. In doing so she proposes a characteristic of documents and brings the reader closer to the difficulties they pose for the researcher. She also takes this opportunity to review the information that can be obtained by embarking upon the laborious task of studying the discussed material. | ||

| Mark Golberg | Borderline. Gratitude. Warning  | 203 |

The oeuvre of Schulz is a polycultural phenomenon containing living traditions of Polish literature spanning from Adam Mickiewicz to the young Poland period. The author’s strong ties with Drohobycz are also supposed to recall the impact exerted upon him by Ukrainian culture and the typological convergences of his works with Ukrainian lyrical poetry, i.a. that of Vasyl Stefanyk. Finally, Schulz was brought up in a Jewish family, was familiar with Jewish rites and customs, and never forgot his Jewish descent - traits of Jewish mentality are vividly discernible in his writings and reside in their profound structure and sub-text. We encounter in Schulz’s oeuvre numerous reminiscence of world literature - from antiquity and the Bible to contemporary authors. These are signals of a prolific dialogue conducted with the literature in question. Schulz referred to the Romantic poetics of a two-world: a dull provincial small town assumed the form of an extraordinary realm of dreams, and the visible material quality of things reveals their profound essence and deeply hidden poetry. Such poetics of the Schulzian two-world is close to the creative quests of German Romanticism, especially Jena Romanticism and Hoffmann, and becomes embodied in the mythologisation, stylistics, and architectonics of works written by the author of Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą (The Hourglass Sanatorium). The Bruno Schulz dylogy is an entity bonded by the narrator who possesses all the properties of a lyrical subject and actually is such a subject prone to contemplation and self-reflection; already these traits allow to state that Schulz’s prose is lyrical. Moreover, the leading role in Schulzian narration is played not by external events, but by a reflection of the inner life of the subject, deliberations, and lyrical landscapes. Schulz was capable of perceiving in every detail of life something concealed behind empirical reality, and saw the transcendent and transcendental in everything. His world is thoroughly metaphorical since in it the metaphor is not an artificial setting of the story but a manner of thinking; it is not a hidden comparison in the Aristotelian meaning of the term but a transformation of reality, the creation of new worlds. The writer’s presented world is tantamount to the unity of poetry, myth, and philosophy, and in it philosophical features cease being abstractions but assume the form of fascinating images, thus building the foundation of a poetic perception of the world. Schulz’s works contain a great potential opening up assorted interpretations and, at the same time, causing their conflict. The most correct approach to an interpretation of his writings appears to be a combination of hermeneutic, phenomenological, historical-comparative, and fictional approaches; treating culture as a palimpsest and a theory of intersexuality will prove to be rather ineffective. The Schulzian oeuvre, emergent on the borderline of cultures, carries enormous spiritual energy. Schulz is indispensable for our times and, simultaneously, his fate is a warning and a call for watchfulness and respect for people and nations. | ||

| Wiera Meniok | Spring Mists in Drohobycz. A Farewell to Alfred Schreyer  | 209 |

A farewell to Alfred Schreyer – Bruno Schulz’s student, violinist, and resident of Drohobycz. Vera Meniok writes: ”An entire epoch, whose devoted witness was Alfred Schreyer, departed together with him as did the subtle and profound truth of the existence of a person with an immense will to live, possessing an extraordinary skill of stirring joie de vivre and telling about a different life – an increasingly absent world”. | ||

| Ostap Sływyński | Recreating a Brilliant Epoch  | 211 |

Reflections of a participant of the International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobycz. | ||

| Lidia Wiśniewska | Cinnamon Shops and Others in View of the Myths of God and Nature  | 213 |

The article “Cinnamon Shops and Others in View of the Myths of God and Nature” evokes Northrop Fry’s “completeness” applied to those literary works whose formal qualities are beyond explicit type or genre qualifications, proposing a thesis that Schulz’s works also use the completeness of the myths of God (One Form as absolutisation of time, Emptiness as negative space) and Nature (Fullness and Protounity as absolutised space and Chaos as negative time) or similar paradigms (rectilinear time, hierarchical space in linear paradigm, and the coincidentia oppositorum – based space and circular time in circular paradigm). Such a thesis is justified by a motif of a shop occurring in the two series of stories (and forming anti-fictional whole subcutaneously). The Father (called Jacob in the first cycle) and the son (called Joseph N. in the second part) represent two sides of the shop, appearing as a seller and a buyer. The selling father represents the myth of God in the Night of the Great Season due to spiritual creativity, making him resemble Yahweh, and in the Dead Season, by obeying the rules of a specific merchant-knightly order, which assimilates him to a scorpion. In both cases, the other characters, including the mother, are essentially situated on the myth of Nature’s side. However, in the first cycle of the stories (The Visitation, Birds), the aging father is gradually taking the side of the myth of Nature, immersing into its inner dimension (holes in the earth, its own viscera, the labyrinths of its mind) and confronting himself with Yahweh as well as with the mother, who now takes the side of the myth of God, its consciousness and laws. When, in the story Cinnamon Shops, the narrator presents him as living in the circular time and dead in the linear time, the father stubbornly intends to restore linearity thanks to the shop. Finally, “the ultimately dead” father, presented as a boiled scorpion, escapes from the disruptive reality (shop, house, mother, servant) and the myth of Nature, being the only one who is consolidated and established, and thus included into the myth of God. In contrary to his father who examines the ontological dimension of the myths, the juvenile, buying son is interested in their knowledge. In the first cycle, in Cinnamon Shops and The Street of Crocodiles, he tries to reach the erotic knowledge: however, the ecstasy of the romantic night finds its negative reflection in the image of eroticism, its pollution and shallowness, which is incorporated into a destructive and creative duality of the myth of Nature. In The Hourglass Sanatorium, tired of the circular time intricacies, the son yearns for a new, pure rectilinear time but he also sees its threats: the idea of rectilinearity as idée fixe of being perfect makes people automatic machines and only simulates their lack of imperfection. Schulz’s works show a completeness of ontological and cognitive depictions and point to the complementarity. | ||

| Jan Gondowicz | “The Dreadful Drug of Schulzian Cinnamon”  | 223 |

An essay dedicated to the cinnamon shops present in texts by Bruno Schulz, which, as the author demonstrates, “meet the need for the exotic and dreams, thus satisfying the deficit of the wondrous so characteristic for the provinces”. | ||

| Małgorzata Fuszara | Mother, Adela and Others… Women in “Sklepy cynamonowe” and “Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą”  | 227 |

An attempt at an analysis of Schulz’s prose in a manner accepted in women’s studies and with the application of categories used in analyses of this sort. Such an approach calls for focusing on women, their experiences, and viewpoints. In addition, the analysis demonstrates primarily that in Schulzian stories women do not exist as independent subjects but are described exclusively from a man’s vantage point (the “male gaze” category) as well as from the perspective of their sexual attraction, clothes, and appearance (including a “fragmentarisation” of the female body). Such marginalisation of women and their experiences is the outcome of the then prevailing culture, while fragments of Wiosna (Spring) indicate that Schulz was aware of cultural violence present in women’s socialisation and experiences. A dominating part of his prose contains a reflection of the small-town patriarchal world in which women were not the partners of men but persons granted a subjective, subordinate, and marginal social position. Their absence as independent subjects points to “symbolic annihilation”, described in studies on gender inequality, which consists of ignoring or at the very least belittling not merely the role, experiences, and viewpoint of women but even their social presence. | ||

| Jan Gondowicz | Slender-legged Adela  | 235 |

An essay on Adela, the most curious character in Schulzian prose, who appears in as many as 19 of the 32 stories by the author from Drohobycz. | ||

| Olga Czerwińska | Intellectual Texts by Bruno Schulz as a Receptive Palimpsest  | 237 |

The unique diversification of the creative profile of Bruno Schulz generates a quest for specific criteria of evaluation aimed at those horizons, which as if provoke the artist’s un-uniform oeuvre. The idea of bringing up to date the author’s intention in the awareness of the recipient, originating from the context of the hermeneutic conception conceived by Gadamer, accentuated by Hans Robert Jausss, and developed by Wolfgang Iser and Hans Blumenberg, formed the treatment of literature primarily as a sui generis intellectual provocation: by situating the text not only within the perspective of the past but also of the future we render it to a certain extent a historical fait accompli. We measure the entire persona of the Galician author by means of separate texts, fractions of fragmentary reminiscences or correspondence; nonetheless, it is worth keeping in mind that each intellectual “text” becomes not one of the small “deaths of the author” but a special form of his transformation, preserving these ingested and accomplished earlier. The article stresses the conspicuous symphonic character of Schulz’s achievements, the organic similarity of all his multi-genre artistic works (painting and graphic art, verbal images, epistolary collections), the openness of a ”horizon” of all varieties of perspectives, which creates a palimpsest of sorts based on the inter-text and inter-media qualities. Such an approach towards the special form of Schulz’s ”artistic language” (in the widest meaning of the term) and towards describing his general poetics is quite natural. We perceive the unconditional, fanatical recreation of the world and man, which permeates all his drawings, literary texts, letters, and behaviour, and which constitutes the indivisible palimpsest of the portrait of his personality. Hence the reception of the variegated oeuvre of Bruno Schulz should be uniform - each particular text within the context of all the others – as a sui generis integral entity in accordance with the comprehension of such a paradigm proposed by Gérard Genette through the intermediary of its second degrè, containing multi-level factors. In the case of the Schulzian heritage such an approach suggests more precise connotations. | ||

| David A. Goldfarb | Schulz, Dante and Beatrycze | 243 |

| Lothar Quinkenstein | Bruno Schulz Festival 2018. Journey to Reality  | 247 |

An expanded essay-account of the VIII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobycz. | ||

| Elina Świencicka | The Philosophy of Personality in “Sklepy cynamonowe” by Bruno Schulz  | 258 |

The author deliberates on the specificity of comprehending personality in Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) by Bruno Schulz. The work in question was presented as artistic reflection on the consequences of the spiritual world of man abandoned by God. In Schulz’s dylogy we perceive the phenomenon of abandonment by God in a paradoxical manner – via polytheism revealing itself according to the principle of a negation of hierarchy. In such a situation, man resorts to a sui generis provocation of the absolute, which reveals itself in a dialogue. Bruno Schulz demonstrated how in the case of the absence of God the possibility of creating a new world and a new life spreads within matter and every person desires demiurgy. Gradually, there emerges the image of a personal world involving the existence of an eternal formation in accordance with the will of the creative personality; this formation is depicted as eternal existence. Its fabric is created by things and natural components of reality containing a distinctive spiritual essence and experiencing their separate lives. This principle expresses the unstable character of the surrounding world – its split. At the same time, the unity of life divided into numerous small lives remains essentially indestructible and unchanging in each of them. This is precisely the reason why personality becomes dispersed across the world and affiliated with natural reality. The author conceived the subject in a holistic, synthetic, and prompt reception, which produces the effect of renascence that restores the idea of omniunity rejected by rationalists. Upon the basis of an analysis of the subjective organisation of Schulz’s oeuvre the author of the article proposes a conception of the alienation of personality as a way of its self-fulfilment. | ||

| Zoriana Rybczyńska | To Come to Schulz’s Town, or on the Use of Literature as a Guidebook  | 264 |

The various human and place relationships are manifested in literary texts, performative gestures and artistic visions, in cultural practices of traveling, experiencing and acquiring space. In the article on the example of the reception of the works by Bruno Schulz and contemporary tourism and reading practices caused by it are presented considerations about these relations, creating a connective tissue of ideas, expectations and beliefs, defining the ways of reading or traveling and the meaning that we attribute to them. The space of Drohobych (Schulz's hometown) have changed, devastated after the war and transformational transitions, however, remains the reference point for the movement of our imagination, for the revelation of our literal and metaphoric epiphanies, for establishing our personal topophilic relations. Schulz's texts direct our gaze, set the interpretative frame, stimulate of our senses, and activate our empathy. Drohobycz’s visit focused by Schulz’s texts can become a disappointment, but it can discover a different dimension of traveling and reading, discovering us to new existential experience, enabling the creation of “third spaces”. | ||

| Artur Cembik | “Alongside that Hairy Rim of Darkness…”. Creation of the Nomadic Subject in “Sklepy cynamonowe” by Bruno Schulz  | 271 |

The presented text intends to present the protagonist of Bruno Schulz’s The Cinnamon Shops in relation to surrounding reality. The subject of the story, conceived as the author’s alter ego, is an intellectual nomad obliterating boundaries between the real world and the created one. According to the theory propounded by Rosi Braidotti his characteristic features include total independence and distrust of existing conventions. The protagonist’s ability to incessantly translocate himself, and his experiences of liminality are disclosed in an excess of stylistic measures and prove the author’s linguistic extravagance. The subject of the story is doomed to wander, a fact that he fully accepts by consenting to a world endlessly changing in front of the reader’s eyes. | ||

| Jana Waldhör | When Places Disappear behind Myth’s Language: the Lush Rampancy of Childhood Memory in Bruno Schulz’s “The Cinnamon Shops”  | 275 |

The paper tries to apply Walter Benjamin’s concept of memory and history, formulated in Passagen-Werk, Berliner Chronik and Berliner Kindheit um 1900, as an instrument to Bruno Schulz’s prose volume The Cinnamon Shops. Not only are there only three days in between the date of birth of these two authors, but also both became victims of the Holocaust. In spite of one being a ‘Western’ and the other being an ‘Eastern Jew’, their approach to childhood memory and their working with and on it resembles, as will be examined. Based on Walter Benjamin’s idea of history and memory, which is strongly connected to the paradigm of spatiality, the autobiographical sketches and snapshots in Bruno Schulz’s prose volume The Cinnamon Shops will be examined more closely and a topography of childhood will be revealed. By doing so, terms such as Tiefe der Erfahrung, Archäologie des Erinnerns and raumgewordene Vergangenheit, which Walter Benjamin formulated in several papers, will be revealed in Bruno Schulz’s approach to his childhood memory. The consistency of the authors’ approach with and on their childhood memories will be illustrated with two examples. Subsequently, Drohobycz, which is not only the place of Bruno Schulz’s childhood, but also operates as a place of a triple bond, will be examined in more detail on the basis of several passages in The Cinnamon Shops. Including relevant literature, such as Gaston Bachelard’s La poétique de l’espace and the use of terms such as parergon (Jacques Derrida, La vérité en peinture) and simulacrum (Jean Baudrillard, Simulacres et Simulation), Bruno Schulz’s view at the spaces of his childhood is to be substantiated. It soon becomes apparent that Bruno Schulz’s Drohobycz only exists under the danger of disappearance for two reasons: on the one hand due to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and on the other hand due to the onset of industrialization. Finally, it is Bruno Schulz’s language of myth, which, like the lush gardens in his memories, forces its way into the Galicia of his childhood and gradually makes it vanish beneath it | ||

| Magdalena Wasąg | The Imaginary Townlet. Schulz in a Letter by Alicja Mondschein-Dryszkiewicz to Henryk Bereza  | 283 |

For years Alicja Mondschein-Dryszkiewicz met important and highly regarded artists. In her correspondence with Henryk Bereza she recalled such luminaries of the world of culture and art as Witkacy, Gombrowicz, Schulz, or Hłasko. On 15 October, under the impact of reading Janusz Rudnicki’s Schulz ‘92, she wrote a letter addressed to Henryk Bereza in which she once again mentioned her familiarity with the author from Drohobycz. In doing she characterised the local milieu and the small town – Schulz’s birthplace, presenting her interpretation of the life and works of the author of Sklepy cynamonowe. These recollections supported by “narrative talent”, which according to Bereza’s assurances did not deprive the account of authenticity, sound credible. Dryszkiewicz attempted to tell Bereza an unusual and complicated biography of Schulz-the author; in her recollections she referred to Schulz’s experiences of provincial life and endeavoured to evoke the stifling atmosphere of the local ghetto. All traces recorded in this letter produce a portrait of Schulz inextricably connected with the small town – the site of his life and creative work, and the space of inspiration and longing. | ||

| Bruno Schulz: Trajectories, Orbits, Constellations and Other Spaces | ||

| Serhij Żadan | Drohobycz and Environs  | 287 |

“In Drohobych we all had the same acquaintance. His name was Schulz. Try to recall or imagine him“ - wrote Serhiy Zhadan in an essay originally published in the volume Drohobycz. Księga wierszy wybranych (2014–2016). Here, we cite also three poems from this collection. | ||

| Serhij Żadan | Three Poems from the Volume: Drohobych  | 293 |

“In Drohobych we all had the same acquaintance. His name was Schulz. Try to recall or imagine him“ - wrote Serhiy Zhadan in an essay originally published in the volume Drohobycz. Księga wierszy wybranych (2014–2016). Here, we cite also three poems from this collection. | ||

| Paweł Próchniak | “The Drohobych Book” by Serhiy Zhadan Note | 294 |

| Wiera Meniok | Twilight in Schulz and his [Schulz’s] Shadow in Zhadan  | 295 |

An important effect of the International Bruno Schulz Festival as well as an expression of Schulz’s inspiration in the oeuvre of Serhiy Zhadan, a cult Ukrainian poet and writer is a volume of his poems, Drohobych, in Jacek Podsiadło’s translation. Zhadan reads Drohobych with the “letters of cinnamon shops”, looks for Schulz’s traces in it and notices his shadow. Schulz’s shadow appears in Zhadan’s works between darkness and dawn, between sickness and recovery, between sadness and joy, and between dilemma and salvation. Drohobych will be always associated with Schulz for the author of the Drohobych volume primarily in his imagination. Schulz has become “a private history of attachment to the city” for him and offered him a special state of initiation and inspiration. Schulz’s shadow in Zhadan is either a harbinger or a trace, either expected or sought after and has epiphanical and eschatological meaning as well as twilight in Schulz’s short stories, including Spring and July Night. Twilight as well as shadow is a common place in both Schulz and Zhadan and the most unexpected and painful things can emerge from it. | ||

| Natalia Filewicz | Exhibition about Exhibitions: Bruno Schulz among Artists of His Time at the Boris Voznitsky Lviv National Art Gallery  | 304 |

The article focuses on ideas and surveys associated with the exhibition: Bruno Schulz among Artists of His Time, featured at the Lviv National Art Gallery in 2018 as part of the VIII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych. The display presented artists who together with Bruno Schulz took part in exhibitions held in Lwów in 1922, 1930, 1935, and 1940. The Gallery collections store works by almost all these artists, up to now rarely or never shown. The exhibition demonstrated the position of Schulz’s works alongside those by other artists within the context of trends of the period. The author also discovered forgotten reviews and stressed that artists on show in Lwów – of assorted nationalities and representing diverse views – shared a striving towards creative quests as well as a dramatic fate. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | VIII Festival. Artistic Dimension: Exhibitions, Concerts, Spectacles…  | 311 |

Description and analysis of the artistic events of the 8th Schulz Festival in Drohobych. | ||

| Bohdan Zadura | Revita  | 322 |

Recollections from the V and VI edition of the International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobycz. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | A Suicide, a Doctor and a Writer. Paradoxes of Stories from “One and a Half Cities”  | 325 |

The article refers to an authentic story of a suicide committed by a young Jewish woman, who on her deathbed converted to Christianity. This event roused the residents of Drohobycz – with Poles and Jews reacting differently – but did not generate an acute conflict. The daily life of those two nations living in Drohobycz was interwoven. The author treated the story as a pretext for touring the contexts of the period and the life of Bruno Schulz. This is the reason why Grzegorz Józefczuk wrote about, i.a. religious and medical authorities, leaders and the crowd, illnesses and cemeteries, oblivion and survival. | ||

| Grzegorz Gauden | Both Polish and My Adventures with Bruno Schulz  | 331 |

Lecture given in the course of the inauguration of the VII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych in 2016. Here, Grzegorz Gauden described the assorted contexts in which he enjoyed an opportunity to encounter the person and texts by Bruno Schulz. | ||

| Jerzy Kandziora | Hidden Witnesses, or What is Left in Ficowski’s Book and in the Real World After Two Friends of Bruno Schulz  | 335 |

An attempt at a reconstruction of the fate of two witnesses of the life of Bruno Schulz: the Drohobycz lawyers Michał Chajes and Izydor Friedman (after the war: Tadeusz Lubowiecki). Their reminiscences and accounts served Jerzy Ficowski writing about Schulz – the author of this study, however, indicates that they were treated in a rather selective manner. Jerzy Kandziora demonstrated that both men “played a particularly great role in the early formation of Ficowski’s knowledge about Schulz and provided him with very copious characteristics of the man of letters […]. Paradoxically, these were persons who in the main text of Regiony wielkiej herezji never appeared as authors of such extensive source accounts”. | ||

| Ryszard Nycz | Bruno Schulz: Art as Cultural Extravagance  | 341 |

Essay about extravagances presenting Schulzian texts as significant – all that “strangeness” and “oddity” typical for him. The author demonstrates that they should not be omitted in attempts at interpretations profiling the deciphering of this prose in a new, insightful, and informal perspective. | ||

| Jerzy Jarzębski | Schulz – Ironic Order and Seductive Discourse  | 351 |

An examination of key mechanisms governing the entire oeuvre of Bruno Schulz, with the article pertaining in particular to those questions of the aesthetics of the works of the author of Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą (The Hourglass Sanatorium) that are linked with an artistic creation of reality and an attitude towards the real world, inscribed into that creative gesture. Jarzębski is interested primarily in the “ironic order” dominating the world depicted in Schulzian prose. This order has an underpinning of irony and, moreover, is closely connected with “passion”, which makes its presence known in the “seductive” element of each story – a fact that Schulz understood well and in assorted ways played out artistically. The oeuvre of the author of Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) is an affirmation of order and beauty, but this is an affirmation whose tools are “the grotesque” and “laxity” (this is why in the case of Schulz beauty is closely affiliated with tawdriness and ugliness, and order – with carnival-like chaos). At the same time Schulz’s imagination often runs in a circle – from mundane order towards strange fantasticality breaking the framework of time, towards something unusual participating in some sort of an out of the ordinary order, so as to ultimately return to the order of everyday time and the mundane. In this fashion the “explosion of fantasy” and “féeries of poetry” end in “bankruptcy” and are fulfilled in a “spectacular fiasco”, which denotes a return to order and an affirmation of daily life. This whirling circle is set into motion by a dual force – gravity and irony, sensitivity to the dramatic nature of existence and the farcicality of life. The force in question is also that of spinning a story. The latter is always a form of founding the world – a recounted world gains a “putting-in-order sense”. Simultaneously, the same story is seductive and does not make pronouncements about the world but tries to win over the listener (reader); this, in turn, is the reason why it becomes a form of an ”erotic game”, active flirtation involving “the grotesque” and “beauty”, (male) “tawdriness” and (feminine) “perfection”. Jarzębski concluded: “Even if the order of the world is in some way objective, it enters into our life and begins to mean something to us together with the birth of desire – this is why Schulzian stories are in their profoundest essence spectacles of eternally vital passion”. | ||

| Roman Dzyk | Dostoyevsky and Schulz  | 356 |

The article focuses on inter-textual connections between Bruno Schulz and Fyodor Dostoevsky, a theme neglected by experts on Schulz. Upon the basis of the only mention of the Russian classic in the preserved oeuvre of the Polish man of letters Roman Dzyk proposes a methodological approach to the reconstruction of a possible inter-textual reception. This method foresees, i.a. an identification of editions of Dostoevsky’s work available to Schulz and studying the possible mediated impact of the functioning of Dostoevsky in Polish (Nałkowska, Witkiewicz, Gombrowicz) and world literature and culture (Freud). Special emphasis is placed on similarities in the treatment of the principles and limitations of realism in the case of both authors, demonstrated in their particular declarations. The Dostoevskian creative method thus reveals itself via the conception of mystical realism. In the case of Schulz analogous mystical interest comes down to mythological realism. Owing to the lucid presence of Schulz’s Doppelgänger and Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, the article outlines a perspective of a more profound inter-textual analysis, which does not restrict itself to the indicated texts. | ||

| Polina Justowa | Bruno Schulz in Russia  | 362 |

A presentation of the history of translations of works by Bruno Schulz into Russian as well as assorted cultural initiatives focused in his oeuvre, spanning from the first edition of 1989 to the present day. Official Soviet literature did allow such “strange” and “degenerate” works to speak and thus they were usually presented in all sorts of editions functioning in so-called samizdat circulation. For the first time prose by the myth-maker from Drohobycz resounded in Russian in the samizdat socio-literary periodical “Mitin Zhurnal” in 1985. The work in question was Samotność (Loneliness), translated by Olga Abramovich. In 1989 “Rodnik” (1987–1994), a Latvian-Russian periodical published in Riga, presented prose by Bruno Schulz translated by Igor Klekh. The situation improved considerably in the 1990s when was finally permitted to print and read everything. The last decade of the twentieth century produced a whole gamut of Schulzian publications conspicuous for excellent translations by the writer and poet Asar Eppel. In 1993 the Gesharim publishing house produced book versions of Sklepy cynamonowe (The Cinnamon Shops) and Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą (The Hourglass Sanatorium). After a lengthy interval, in 2011 the “Text” publishers issued the volume: Salvaged, containing all the preserved texts by Schulz translated by Asar Eppel. On the other hand, the small number of literary studies discussing the phenomenon of Schulzian prose remains thought-provoking, although in more recent years this bewildering situation is compensated by Internet publications and cultural initiatives, i.a. material available on the Radio Svoboda website prepared by the poet and journalist Elena Fanailova and a Russian version of the portal: culture.pl, performative projects (the High-heels Project by Anna Kaszuba-Dębska, on show in Moscow in 2013), an exhibition of drawings by Schulz held as part of the B. Schulz Festival (Moscow, 2018), et al. | ||

| Paweł Huelle | Four Drohobycz Poems  | 366 |

The Drohobycz poems by Paweł Huelle – one of the most outstanding Polish contemporary prose writers and essayists – are micro-essays reflecting on the elements of the Drohobycz imaginarium perceptible in a discursive diction, as well as the presence in that imaginarium of the biography of Bruno Schulz together with the important motifs of his oeuvre. Huelle considered, predominantly, memory landscapes linked with landscapes of death (in their historical and existential dimensions), the visibility of the world and the radical blurring of its image in the wake of the Shoah catastrophe, and, finally, the role of art as a form of seeking and reviving our sources of existence. | ||

| Adam Pomorski | Translations of Poems from Antologia poezji ukraińskiego modernizmu. Od Łesi Ukrainki do Bohdana Ihora Antonycza | 369 |

| Adam Michnik | Bruno Schulz for the World and for Ukraine  | 375 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz jako filozof i teoretyk literatury. Materiały V Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2014, p. 19-23. | ||

| David Grossman | The Age of Genius  | 378 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz jako filozof i teoretyk literatury. Materiały V Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2014, p. 49-56. | ||

| Taras Prochaśko | *** My great-grandfather lived in Drohobych for several years...  | 381 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz jako filozof i teoretyk literatury. Materiały V Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2014, p. 61-64. | ||

| Wiktor Jerofiejew | A Boiled God  | 383 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz jako filozof i teoretyk literatury. Materiały V Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2014, p. 78-85. | ||

| Shalom Lindenbaum | Bruno Schulz – the Artist and the Aesthete: The Concept of Bruno Schulz’s Literature and its Embodiment in his Creative Works  | 387 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz jako filozof i teoretyk literatury. Materiały V Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2014, p. 267-279. | ||

| Jurij Andruchowycz | In Old Apartments There Are Rooms, or I Know a Certain Sea Captain. Schulzian Versions of Space With the Addition of Time  | 393 |

English version in: Bruno Schulz: teksty i konteksty. Materiały VI Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2016, p. 40-58. | ||

| Andrij Lubka | Inconceivable Ukrainian Patriotism, Or What Do We Need Kolomyia For  | 402 |

Two feuilletons by Andriy Lubka loosely connected with Bruno Schulz and published earlier in Kontrakty.ua and Day.kyiv.ua. | ||

| Andrij Lubka | All Roads Lead to Drohobycz  | 404 |

Two feuilletons by Andriy Lubka loosely connected with Bruno Schulz and published earlier in Kontrakty.ua and Day.kyiv.ua. | ||

| Jurij Wynnyczuk | Tasting Schulz  | 405 |

Lecture given at the inauguration of the VII International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobych in 2016. Yurij Vynnychuk described his private reception of Schulzian prose which, he explained, “he absorbs in small doses, just like ice-cream in his childhood, rolls the metaphors on his tongue, tastes their flavour on the roof of his mouth, and tries to keep it as long as possible”. | ||

| Paweł Próchniak | Bird’s Matter Contribution to the Reading of “The Night of the Great Season”  | 407 |

The author embarked upon the question formulated years ago by Władysław Panas, who wrote that remarks on time opening Noc wielkiego sezonu (The Night of the Great Season) are “a presentation of Schulzian poetics“ – they fulfil a “meta-poetical function” and comprise a “mini-study” on poetry and its matter. The thus seen introduction to the story appears to be a “theoretical introduction to poetics”, followed by a description of the creative act – an exemplification of “a presentation of poetical doctrine” translating the premises of formulated poetics into concrete immanent poetics and, at the same time, developing a quasi-discursive “poetical treatise” into an enigmatic “treatise about creativity” itemized as images and the plot. The author of the article is interested mainly in the prime motifs of the treatise in question (in particular “time” and the “dynamic state”) as well as the fabric woven out of those motifs – the matter of Schulz’s art and its concealed warp. Essay about extravagances presenting Schulzian texts as significant – all that “strangeness” and “oddity” typical for him. The author demonstrates that they should not be omitted in attempts at interpretations profiling the deciphering of this prose in a new, insightful, and informal perspective. | ||

| Elżbieta Ficowska | Letter  | 412 |

Letter written in 2005 by Elżbieta Ficowska to Vera Meniok. | ||

| Jerzy Ficowski | This is Why I Find It So Difficult to Stop  | 413 |

Statement by Jerzy Ficowski (1924–2006), researcher studying the oeuvre and biography of Schulz, made on 19 November 2003 upon the occasion of opening the so-called initial version of the Bruno Schulz Museum in Drohobych. | ||

| Wiera Meniok | Bruno Schulz Museum in Drohobych. Several Remarks on the Genealogy of the Site  | 417 |

Article on the origin and idea of the Schulz Museum in Drohobych and the history of its establishment in Schulz’s office. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | Stories of a Curiosity Cabinet. Several Remarks on the Genealogy of the Site  | 421 |

This essay describes the Bruno Schulz room-museum in Drohobych and the curios, collections, and artistic undertakings associated with it. | ||

| Sofija Andruchowycz | More Than Everything  | 429 |

Artur Sandauer – literary critic, essayist, and translator – maintained that he read the manuscript of Mesjasz. According to his account the opening lines were as follows: ”you know – mother said to me in the morning. – The Messiah has come. He is already in Sambor”. Quite possibly this novel still exists somewhere – in the private collection of some egoistic maniac or in special services archives. Or perhaps it has never been written. There is nothing more to be added. The sentences remembered by Sandauer contain everything: conflict and drama, the Oedipal conflict and a universal social element, a post-Apocalypse, a provincial theme, an identity crisis, collapse and hope, the end of time, frenzy, faith, miracles, contradictions of human nature, fantasies and reality. They are even more excellent than Hemingway’s lines about baby shoes because we are dealing with a novel. One can say a lot, more and more, and yet say nothing. One can say a few words – and say more than everything. | ||

| Wiera Meniok | “Unsaved” Bruno in Ukrainian Space-time  | 431 |

English version in: Współczesna recepcja twórczości Brunona Schulza. Materiały naukowe III Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Brunona Schulza w Drohobyczu, ed. Wiera Meniok, Drohobycz 2009, p. 249-260. | ||

| Wira Romanyszyn | Bruno Schulz’s heterotopies as a geopoetic sign  | 437 |

The Schulzian character identifies himself with the city and is therefore not only aware of the urban space but also creating it, as he overcomes a set of obstacles, crosses boundaries and limits in creating labyrinth spaces (mazes of buildings, mazes of nature, mazes of time, and mazes of mental realm). His wandering, however, are taking place not only through the streets of the city but also through the labyrinths of sleep and night. In Schulz’s works, dreams and reveries are not so much the outcome of the individual author’s process of implementation of imagination and of other mental creative phenomena as they are a symbolic outlook upon the image that becomes the most optimal way to achieve the extra-verbal actuality – i.e. the actuality in absolute terms and not the individual symbolic actuality. A number of authentic toponyms and loci, presented as a merger of autobiographical memory and the memory of culture in Bruno Schulz’s prose, is building up a range of heterotopies, peculiar places – like, for instance, the heterotopy of the home and the street and their respective subheterotopies of the room, the corridor, and the stroll through the streets; the heterotopy of the train and of the sanatorium as a concealed marginal side of the real actuality; the heterotopy of the Book, of the stamp album and panopticon (waxwork exhibition) as an implementation of the connection between individual and the collective history. All of the above go way beyond the real time and space of the city and constitute the sign of geopoetic knowledge of the city – viewed both locally and internally (i.e. of the author and the narrating character) and internally, as common knowledge which anyone may access. From the standpoint of geopoetics, the important point for all of these heterotopies is the experience of the places and the role of a specific place in that experience. | ||

| Keti Kantaria, Wiera Meniok | I Absorbed Schulz with a Child’s Imagination - Conversation  | 443 |

Conversation held by the curator of the Bruno Schulz Festival with Keti Kantaria, translator of the prose of the festival’s protagonist into Georgian.

| ||

| Jerson Fontana | Bruno Schulz Protagonists in the Brazilian Theatre. A Turma do Dionísio Presents „Sanatorium”  | 446 |

The author describes work on a theatrical adaptation of three stories by Bruno Schulz, which resulted in a monodrama: Sanatorium, the theatrical and actor conception of this adaptation, and the reception of the spectacle in Brazil, Poland, and Ukraine. The main part in the Fontana adaptation is played by the actor’s body and motion, expression and message via – apart from the word – the gesticulation of each dramatis persona and the manner of making use of the space of the stage. Ultimately, concentration on movements and space is to emphasise the inner life of the protagonists, since this is the aspect most vividly outlined in Schulz’s prose. Sanatorium is a spectacle about persons involved in an encounter. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | Schulz w Lublinie. Nasza tutaj specjalna rola  | 451 |

The sole preserved manuscript of a fragment of a story by Bruno Schulz survived the turmoil of history in the archive of the “Kamena” periodical, issued in Chełm near Lublin. The author attempts to confirm the conviction formulated by Prof. Władysław Panas, namely, that the town of Lublin enjoys a status distinguished in questions associated with Schulz and the reception of his oeuvre. Schulz is present in Lublin in assorted periods due to increasingly new projects and events - scientific, educational, and exhibition - while the Bruno Schulz Festival Society established here is the Polish organiser of the festival held in Drohobycz. | ||

| Jurij Andruchowycz | Bruno and Porn. Drohobycz 2007  | 455 |

Text presented at the IV International Bruno Schulz Festival in Drohobycz in 2010, published also in the book Leksykon miast intymnych (2014). | ||

| Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak | What is a Map?  | 459 |

Reflections on the semiotics of a map conceived as a text – within the context of the topography of Drohobycz/Drohobych and the oeuvre of Bruno Schulz. | ||

| Grzegorz Józefczuk | Map of Drohobycz | 462 |

| Jerzy Jacek Bojarski | Legend to a Map of Drohobych | 465 |

| Wiera Meniok | “Anonymous and Cosmic” Map of Drohobych According to Bruno Schulz. Itinerary  | 474 |

Description of the historical and contemporary space of Drohobycz / Drohobych – read within the context of Willa Bianki. Mały przewodnik drohobycki dla przyjaciół, an essay by Władysław Panas. | ||

| Jerzy Maria Pilecki | Contemporary Plans [Not Maps] of Drohobycz  | 478 |

List of available plans of Drohobycz with a detailed description of particular versions and editions. | ||

| Jerzy Maria Pilecki | Association of Friends of the Land of Drohobycz Note | 480 |