Issue 2007/2 (277) -

| Johann Wolfgang Niklaus | The Anthropology of the Theatre and the Reconstruction of Mediaeval Liturgical Drama  | 4 |

The author describes the manner in which the activity of the Schola of the Węgajty Theatre, focused on the reconstruction and presentation of mediaeval liturgical drama, refers to the anthropology of the theatre. The text is an introduction to a series of studies published in this issue, dealing with the quest conducted by the artists of the Schola in cooperation with humanists, as well as the purely artistic, historical-scientific, theological, anthropological and cultural-studies research carried out for the more than the past ten years. Upon the basis of the example of an expedition to Castelsardo in Sardinia, a description of Holy Week processions, the so-called sacre rappresentazioni – depictions of the saints, and a meeting with the Fraternity of the Holy Cross, the author demonstrated the essential rank of the anthropological approach, against the backdrop of historical studies, together with the creative tasks of the company, i. e. a reconstruction of Ludus Passionis, the oldest Passion play in Latin Europe. This monumental liturgical drama is contained within a thirteenth- century manuscript known as Carmina Burana, from the Benedictine monastery in Kaufbeuern and kept in the National Library in Munich . What could be the outcome of the described experiences, apart from the purely cognitive results, obvious for the activity of the company? Meetings with such persons as members of the fraternity from Castelsardo and other representatives of then world of living tradition open up a door to the world of the Holy Game (Sacer Ludus) envisaged by Gerardus van der Leeuw, which in its pure and earnest form is what our contemporary life lacks. It is the author’s sincere hope that the proposed selection of texts and material will describe the fashion in which a theatrical company may build, enhance and realise its tasks by basing itself on instruments moulded by the anthropology of the theatre. | ||

| N. N. | 9 | |

| Błażej Matusiak | Commentary to The Testimony of Egeria  | 15 |

A brief theological reflection serves as an introduction to an ancient description of Paschal liturgy in Jerusalem . There are two extant traces of the Jerusalem Holy Week liturgy: the catechesis of Bishop Cyril and the testimony of Egeria who went on a pilgrimage from Gaul to the Holy Land . The Holy Week in Jerusalem was devoted to tracing the sites of the Passion. ”The road” is a key concept in Christianity. The earthly life of Christ is composed of His exodus and a return from this world to His father. The life of Christians is an emulation of Christ and a path leading to the Home of the Father, while a pilgrimage and a procession are copies of that road, The very essence of Easter is such a recollection of the path traversed by Jesus, which offers participation in all that which is remembered, The Passover of Christ is not a part of the past but an eternal event, and the role of liturgy, including liturgical drama, is to guide towards eternity. This is probably the reason why the Egeria text continuously mentions infinite matters: luminescence, the glimmer of candles, and the voices of singers. If according to Nikolaus Harnoncourt it is worth performing only that sort of music, which proves alive today, then a return to the liturgical drama of yore even more so cannot denote a departure into the past. | ||

| Marcin Bornus-Szczyciński, Johann Wolfgang Niklaus, Michał Siciarek, Janusz Palikot, Wojciech Michera, Błażej Matusiak, Rafał Lewandowski, Ariadna Lewańska, Anna Kuligowska-Korzeniewska, Michał Klinger, Rafał Huzarski, Jacek Borkowicz | Liturgical Drama Today. Doubts, Hopes, Visions . A Register of a Discussion Held in a Catholic Intelligentsia Club  | 19 |

The titular discussion was attended by theatre experts, theologians, clergymen, musicologists and anthropologists. Theoreticians and practicians. The friends and lovers of Schola of the Węgajty Theatre. The multi-motif debate concerned assorted aspects of the Schola’s activity. Much was said about the importance of the quest conducted by the Schola, aimed at a reanimation of liturgical drama in Poland and its introduction into a living theatrical-religious circuit. The participants of the discussion showed the distinctness of the undertakings pursued by Wolfgang Niklaus and his company against the backdrop of the theatrical avant-garde associated with Kantor and Grotowski. The topic of the debates included the difficult and highly ambivalent revalorisation of tradition, indicating the accompanying threats (a tendency towards turning the theatre into a museum), but also the positive side of such ventures (a living, currently created and constructed tradition). The speakers demonstrated the obstacles which hamper the staging of liturgical drama, connected with an incessant balancing between the sacral and the secular. The great merit of the discussion was its extremely personal nature. It must be stressed that in many cases erudite theoretical-historical statements or those concerning musical performances, were accompanied by totally private confessions made by musicians collaborating with the Schola or the participants of the dramas presented by this theatrical company. Their views not only stimulated the discussion, but also proved irrefutably that despite certain differences in the assessment of the Węgajty Theatre, its members perceive the encounter with liturgical drama as an essential experience. | ||

| Julian Lewański | The Artistic Aspects of Dramatised Liturgy  | 32 |

The lecture considers the poetic of the mediaeval liturgical drama. By resorting to the liturgical recommendations contained in Polish Church texts from the fifteenth and sixteenth century, the author reconstructed in detail the course of the dramatised rituals of the Holy Week (Palm Sunday, Elevatio Crucis, Descensio ad infernos, Visitatio Sepulchri), and analysed the measures of theatrical expression applied therein (i. a. a concentration of contents, simultaneity, the effect of strong contrasts and vivid oppositions, the ”blurred” personality of some of the dramatis personae). The rituals in question were an act of piety and, at the same time, a spectacular drama featured on a stage without footlights since the whole town could become a theatre. The author claims that if we wish to understand properly the artistic merits of liturgical drama, we must become familiar with entirely new aesthetic rules. | ||

| Magdalena Mijalska | An Introduction to Ludus Danielis. A Guide to Several Ranges of the Liturgical Theatre  | 38 |

The author began her presentation of the structure of the liturgical drama entitled Ludus Danielis – a sui generis ”spectator’s guide” – by examining the text of the manuscript from Beauvais. She went on to consider the dynamic of the reality created in the church interior by the theatrical word and gesture. In doing so, she indicated such features as the vanishing contrast between the actors and the spectators, the reduced significance of the plot and the characters, the increased rank of the structure as well as the deceleration of the rate of events. In this sort of theatre, the centre of gravity is transferred from the plot to ”contemplative activity”, the celebration of the ”happening”, and the dynamic of relations between man and God. The author also studied from a meta-theatrical vantage point the question of the part and the actor, taking this opportunity to cite the theatrical reflections of Juliusz Osterwa (his plans of transforming the Reduta Theatre into a Brotherhood of St. Genesius). | ||

| Marcel Peres | From Moravia to Toledo  | 43 |

Marcel Pérès, one of the greatest singers, musicologists and researcher on the field of traditions of sacred chant presents the tradition of mozarabic chant of the brotherhood Andavìas in Spain . To show the complexity of this topic, he draws the wide context of his meeting with Andavìas tradition: the way that led him and his friend of Festival in Jarosław, during over ten years of tracing and studying different kinds of chant traditions. He shows links between the practical use and contemporary existence of the treatise of Hieronymus de Moravia, Greek Byzantynian chant, Corsican tradition of polyphony and the history of appearance and development of the mozarabic chant in Spain . He is pointing differences and similarities between the living tradition and showing their actual condition, meaning and importance for the revival of the West Christian sacred chant. The article is based on Mercel Pérès’ speech from the International Festival of Early Music “The Song of Our Roots” in Jarosław in 2006. | ||

| Michał Siciarek | On the Performance of Bernardine Pious Songs at the Turn of the Fifteenth Century  | 46 |

Introductory data are to recollect the history of the appearance of the Bernardines in Polish lands – the foundations of the particular monasteries, and the origin of the Bernardine tertiary nuns and secular fraternities. The author went on to examine briefly the Franciscan or Bonaventuran model of Passion devotion, especially the forms, motifs and prayer schemes particularly popular during the Late Middle Ages among the Franciscans. General comments on piety are followed by a Polish-language Franciscan repertoire: catechism songs, chaplets, the hours and para-theatrical forms – Nativity and Easter Passion plays. This repertoire possessed its own performance milieu – the subsequent fragment outlines views concerning the performance of songs by the Bernardine monks and nuns or secular brotherhoods. Next the author discussed four monuments preserved in Bernardine sources – two songs by Władysław of Gielniów: Jezusa Judasz przedał and the chaplet Kto chce Pannie Maryi służyć, followed by examples preserved in a manuscript of Psalterium Beatissimae ac Gloriosissimae Virginis Mariae from Lwów and, finally, Coronula sive Koronka written by Brother Seweryn from Goblin. The text ends by briefly mentioning the impact exerted by the Council of Trent and the post-Council Catholic reform upon the development of Franciscan folk piety, achieved by, i. e. regulating the contents of prayer books and the status of the tertiary nuns and piety fraternities. | ||

| Iosif Vivilakis | An Introduction to Byzantine Drama  | 57 |

This lecture starts with a reference to the Byzantine dramatic tradition. The Byzantium , and in particular the church, did not encourage the growth of religious theatre and this is mainly due to theological reasons. During the 15th century, a few years before the end of the Byzantine Empire , the religious theatre of the catholics was characterized as “sect” and “innovation”. They are terms which ostensibly show a theatrophobia, but which are comprehended in the context of the liturgical art of the church and by the study of another view of the world where the catalytic presence of the holy dominates. It is distinctive that only one Byzantine manuscript that emanates from Cyprus gives elements for a theatrical performance of the Passion of the Christ. Nevertheless, some of the researchers tried to apply the conclusions for the religious theatre of the catholic west in the Byzantine culture, attributing to phenomena irrelevant to the stage, the terms “theatre” and “drama”. This study examines the role of theatre in the Byzantium (through the comparison of theatrical experience between west and east) and it negotiates texts and practices that can be considered as belonging to the religious drama, with the literal importance of term: a text with instructions, which is intended to be presented on a stage in front of a crowd. | ||

| Svetlana Butskaya | The Tradition of the Old Believers  | 69 |

An account of the most important aspects of on-the-spot work conducted in the village of Kunicha . The objective of the research was a complex study of the traditional culture of the Old Rite community living in Moldova . The seventeenth-century schism in the Russian Orthodox Church, which was the outcome of the reforms introduced by Tsar Alexey I and Patriarch Nikon remains one of the most dramatic pages in Russian history. The raskoniki (raskol – schism), persecuted by the state and the official Church, tried to preserve not only their faith but also their very lives. Entire settlements, villages and families took Church books, manuscripts and icons along with them while seeking refuge in dense forests along the borders of Russia and even abroad. Many found safety in the lands of pre-partition Commonwealth. Today, Old Believer settlements may be encountered all over the world – in Baltic countries, Romania , Moldova , Turkey , the USA and Canada . The earliest Old Believer settlements in Moldavia (today: Moldova ) were founded in the first half of the eighteenth century. Up to this day, Old Believer Russian villages coexist with those of an entirely different cultural tradition and tongue. Assimilation, however, never took place: the Old Believers vigilantly protect the spiritual message of their ancestors. The Moldavian environment treats the Russians with respect, and accepts the complexity of their nature – enclosure within their tradition and an unwillingness to establish closer contacts; both attitudes are associated with a specific historical plight. During the early 1970s the prosperous and large village of Kunicha was inhabited by more than 4 000 Old Believers. Although the young people tend to leave for the cities, generally speaking the bond with the land of the fathers remains undisturbed, as evidenced by the gatherings of whole families for assorted important holidays, especially Christmas and Easter. The necessity to adapt to a constantly changing social situation is one of the many aspects of the daily life of the village. Openness to transformations is a feature only of economic activity. At the same time, the life of the villagers is still marked by Church festivities and rituals, and the community functions predominantly in a sacral time, closely subjected to the daily and yearly liturgical cycle of Church services. Throughout the whole liturgical year Kunicha resounds with a one-voice znamienniy chant, recorded in a special neumatic notation, similar to the medieval tradition of Western Europe . The Old Believers did not accept the record introduced by Patriarch Nikon – with square notes and polyphony – and continue singing according to the old books. Today, the inhabitants of Kunicha are not forced to flee their foes. The Eastern rite, Ukrainian part of the village respects neighbours who cultivate different customs. Young people from the two parts of the village attend the same school, and from early childhood are taught deference and good will towards both creeds. Peaceful Kunicha carefully distinguishes between the two worlds – it does not impose its lifestyle upon the outsiders but it also does not allow itself to succumb to external impact. | ||

| Rafał Lewandowski | The Epiphanies of Bacchus  | 74 |

Bacchus-Dionysus, seen by A. Solomos in the mosaic of the church in Dafni, is depicted as an allegorical guide to the “hidden theatre”. The essay by R. Lewandowski presents the scientific and poetic work by the author of Saint Bacchus on unknown epochs in the Greek theatre from 300 BC to 1600 AD. In contrast to the West, which separates antiquity from the modern era, the East cultivates the continuum and development of the theatre. The Greek-Christian drama acts as a bridge linking the two epochs. | ||

| Aleksis Solomos | This Scene Takes Place in Heaven  | 75 |

A summary of a chapter from A. Solomos’ book Saint Bacchus, outlining the origin and history of Christian drama as the outcome of the psalm-the Christian dithyramb. Next we have the Song of Songs conceived as the prototype of the opera and psalms intended for choral performance; the introduction of songs into the liturgy by the heretics and the adaptation of Christian psalms to the principles of ancient Greek music; the protest expressed by Christians against psalms, perceived as earthly pleasure as well as their ultimate acceptance by the orthodox Christians and the establishment of the custom of singing poetic songs at the time of the Fathers of the Church. From the fifth century on, Syrian communities witnessed the flourishing of the art of the hymnographers, the most distinguished being Roman Melodos. Hymns and kontakions assumed a dramatic character although not openly (since the theatre was much criticised). Such dramatic features as the absence of the narration and ”theatrical” dialogue, a person in place of an animal character (the serpent with Adam and Eve), and scenes described by the hymnographers reflect Church customs; in the introduction of the forces of darkness (the Devil, Hades, Thanatos) words do not possess the merits of salvation. The hymns display a formal similarity to the secular theatre. The author proposed a hypothesis about the theatrical staging of hymns; in his opinion, The Descent to Hell, enacted up to this day in Greece , is a relic of this practice. | ||

| N. N. | The Officium of the Three Godly Youths in a Fiery Furnace | 81 |

| Michaelis Adamis | The Officium of the Three Godly Youths in a Fiery Furnace  | 83 |

M. Adamis portrayed the Officium of the Furnace, i. e. a liturgical depiction of the story of the Three Youths in a Fiery Furnace, once staged in the main churches of Constantinople and Thessaloniki as well as other metropolitan churches in Byzantium . The author characterised the context of the performance, namely, the sung version of the Divine Service. He also cited information contained in manuscripts and described the arrangement of parts of the officium and its dramatic course. M. Adamis then wrote about the place held by the officium in question in the liturgical calendar, the means of its execution, the type of songs (alternate) and motion (dance) and probable props (furnace, icon). The article mentions the doubts harboured by members of the Church hierarchy about this particular form of the cult as well as the justifications of its defence. Finally, the author outlined the course of his own work on the reconstruction of this form, which had not survived in live tradition. The reader is offered additional information about the tradition of performing the Officium of the Furnace in Rus’. | ||

| Rafał Lewandowski | The Apocryphal Nature of the Painting: Icons of St. Constantine and St. Helen in Anastenaria  | 86 |

Greek refugees from Bulgaria, who during the 1920s settled down in Greek Macedonia, brought over the ancient cult of the Anastenaria, a pagan ritual which merged the Christian holiday of St. Constantine and his mother, Helen. The presented text contains a description of the basic elements of the holiday in question, with special attention paid to the icon of the Anastenarides, traditionally described as the superior component of the cult. In this case, the iconic aspect was discussed in reference to studies dealing with the apocrypha, conducted conducted by Prof. Wiesław Juszczak, as well as an account about similar objects in antiquity, The Apocryphal Nature of the Painting is an attempt at a new look at the icon, with the ultimate analysis avoiding solutions based on the heretic character of the likeness. | ||

| Gerardus Van Der Leeuw | The Holy Game. Reminiscences  | 93 |

The presented fragments come from the second chapter of Sacred and Profane Beauty. The Holy in Art, a book by the acclaimed Dutch phenomenologist. The whole text has been already published in ”Konteksty” more than ten years ago but owing to the importance of van der Leuuw’s reflections for the activity of the Schola of the Węgajty Theatre we have decided to reprint it again, this time in an abbreviated version. In the cited fragments the author followed closely the differences, similarities, and tension between art and religion. In doing so, he portrayed the sacral hinterland of drama and the European theatre. His highly erudite remarks indicate a number of essential religious and symbolic contexts for understanding the role and function of liturgical drama. | ||

| Marcel Peres | Anthropological Meanings of the Space of Liturgy. A Conversation Held by Rev. Claude Barthe with Marcel Pérès  | 98 |

The topics of this conversation encompass liturgical music, both present-day and past, whose recreation and performance are the domain of Marcel Pérès; other motifs include the musical culture ”amnesia” of the contemporary Catholic Church, failed attempts at reform (the reforms proposed by Pius X and the Solesmes movement, Vaticanum II), the quest for traditional sacral space and the liturgical revival. | ||

| Jacek Jan Pawlik | Quests  | 106 |

The search conducted by the Schola of the Węgajty Theatre has two objectives; it involves, on the one hand, the reconstruction of mediaeval manuscripts and, on the other hand, the staging of religious dramas. The author drew parallels between the research carried out by the Schola and the work performed by P. Nawrot, relating to the reconstruction of Baroque manuscripts from Bolivia; subsequently, he went on to compare African ritual drama and the Indian ramlila with the spectacles featured by the Schola. | ||

| Toni Casalonga | A Granitula | 112 |

| Bernardin Škunca Ofm | Traditional Folk Holy Week Passion Processions on the Island of Hvar  | 113 |

The extraordinary Passion heritage on the island of Hvar is regarded as one of the phenomena of Christianity. The author focused on three Passion processions held in the course of the Holy Week, which have survived uninterruptedly from the Middle Ages and remain part of live tradition. Having described the contexts and course of the Theophoric Evening Procession on Good Friday, the ”Following the Cross” procession and the procession to the “Lord’s Sepulchre”, he outlined the historical background, emphasising the significance of the local brotherhoods and confraternities in the transmission of folk religious tradition. The article then considers the concurrence of the contents and form of this tradition with Church liturgy, and concludes about the unquestionable merits of this spiritual and cultural legacy not as a mere historical fact but as a manner of cultivating spiritual life by the congregation itself. | ||

| Katarzyna Jackowska | In Search for the „Total Harmony”  | 118 |

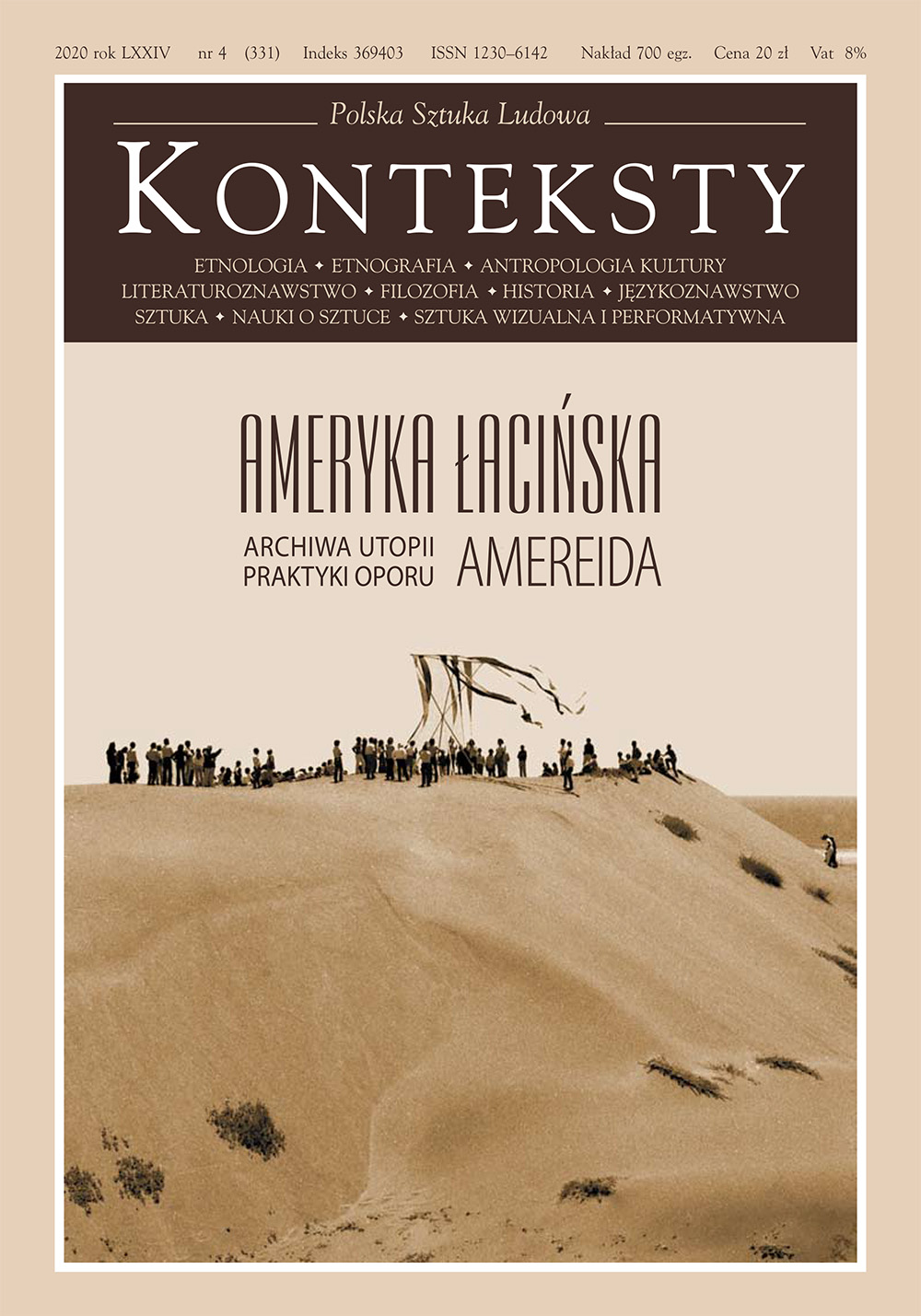

In northern-west coast of Sardegna , in a small town called Castelsardo, there exist a religious brotherhood of medieval origins – Confraternita Oratorio di Santa Croce di Castelsardo. Among many similar groups of profane people dedicating their activity to religious purpose, this one is quite special – because of their tradition of chant and rituals. The culmination of their activity is a Holy Week, fulfilled with chant and processions, with a great procession of Lunissanti. This procession, absolutely unique among other European rituals, takes place on Monday, after the Palm Sunday, and lasts from early morning till late night. The article focuses on few features of brotherhood’s activity and their rituals: dramatic dimension and social context of feasts, and necessarity and possibilities created by real – both physical and spiritual participation – that can help one to find something called by members of the brotherhood “the total harmony”. | ||

| Krzysztof Maria Byrski | Indian Temple Theatre and Liturgical Drama  | 136 |

The invocation, which preceded my presentation in its last line, calls theatre a sacrifice. What does that mean? Hindus basically have a monistic vision of reality. The entire universe emerged from the One that was at the beginning of time. The most important and characteristic feature of our universe is perception. This is why it is termed – perceptive reality. In order to create such reality the One had to become a perceiving subject and at the same time a perceivable object. It just had to die as the One and had to become many, just for the sake of joy of uniting again. This union can be a joyful experience because the one divides itself also into one who desires and into another one who is desired. While watching this loveable sacrifice for the eyes that theatrical performance is, we emotionally identify ourselves with the process of such unification, follow it and experience the joy of merger into One. The question now has to be answered why can it happen in theatre and why it is so difficult to experience in our daily life? The answer is an emotional distance, which we do not have in our normal life, in which we shun unpleasant experiences and seek only pleasant ones. In theatre we enjoy both of them equally. Why? Because the stage reality is not the proper reality of a hero of a play. It is also not the proper reality of an actor or a spectator. Therefore it is a non-particular reality, which evokes non-particular emotional responses. The Kudiyattam theatre of Kerala by its highly conventionalised form makes it even more striking and by associating it with temple ritual turns theatre into ritual as well. | ||

| Anna Łopatowska | The Search for Gesture. My Encounters with the Schola of the Węgajty Theatre Company  | 141 |

My encounter with the Węgajty Schola. The first presentation of the kudijattam theatre in Gdańsk , initial conversations about eventual cooperation with Wolfgang Niklaus and his company. Some basic information about the kudijattam temple theatre from Kerala. Several remarks about the possible application of original gestures in liturgical drama upon the basis of my acting and theatrical experiences as well as those connected with studies on kudijattam. Select information about the manner in which my imagination created gestures for the needs of the performers from the Schola of the Węgajty Theatre. | ||

| Maciej Kaziński | Ludus Passionis – notes | 148 |

| N. N. | Ludus Passionis | 155 |

| Monika Paśnik-Petryczenko | The Schola of the Węgajty Theatre  | 167 |

The Schola of the Węgajty Theatre, an international company of artists active since 1994, deals with the reconstruction of medieval liturgical drama, research into the tradition of sacral songs and tracing the traditional cultures of assorted regions of Poland and Europe . The author discusses the prime programme premises, repertoire, history, work and composition of the company. | ||

| Renata Rogozińska | Nothing Stands in the Mandorla  | 169 |

Jan Berdyszak referred to the icon in Reserved Places and Facies, two series from the 1970s. The first was based on the motif of a flaming rhomb, characteristic especially for the Saviour in Majesty icon, while the second recalls the imprint of the face of Christ on fabric, produced, according to tradition, in a mysterious, divine manner. In both series Berdyszak resigned from a presentation of figures for the sake of a shape indicating the (non) presence of Christ or, to put it differently, an evocation of the places from which God has vanished – an oval of a head without a face, and a rhomb, frequently combined with a circle (mandorla) and a square. The empty space delineated by Berdyszak by means of gaps, fissures and openings becomes “space proper”, a place for contemplating the invisible, an epiphanic space. The material elements of the composition are reduced to a ”casing”, concealing that which remains invisible to the eyes or, to use the name of another series by the same artist, they produce a passe-partout of sorts and, simultaneously, a transition to an entity (passe-par-tout). This approach contradicts the profound humanism of Eastern-rite painting, based on the dogma of the incarnation. The veraicon in particular depicts humanity in a highly expressive and poignant manner within the perspective of suffering and death. This is also the reason why the fact that Jan Berdyszak applied “the true icon of Christ”, or actually its damaged form, to demonstrate the experiencing of God in a void and nothingness, so close to mysticism, could be interpreted as a symptom of radical (provocative?) iconoclasm. The character and message of both series is excellently rendered in Paul Celan’s well-known Mandorla: In der Mandel – was steht in der Mandel?/ Das Nichts./ Es steht das Nichts in der Mandel./ Da steht es und steht | ||

| Renata Rogozińska | Towards the Icon  | 175 |

The icon has become a permanent fixture of Western culture and occupies a prominent place within the “museum of the imagination” of the average viewer. Encountered in churches, both Catholic and Protestant, featured in museums and innumerable art galleries, smuggled across borders, purchased at prestigious art auctions and in street flea markets, created with the preservation of ancient rules and models as well as counterfeit, paraphrased and reproduced, it has gained an army of art lovers across the world. The popularity of Russian Orthodox Church painting has its repercussions also in contemporary art. The spectrum of artistic attitudes and manners of depiction derived from the icon is extensive and situated between two extremities: imitation and purely mental inspiration, illegible in the formal shape of the artwork, artwork, produced on the basis of avant-garde individualism. Artists inspired by the icon include representatives of the most varied currents and conventions. From Klimt and Moreau, the Russian avant-garde, Matisse, Kandinsky, Modigliani, Andrzej Pronaszko, Chwistek, and Hiller, to Mondrian, Berdyszak, Bednarczyk, Damasiewicz, Sadley, Rothko, Tapies, Klein, Wiktor or Warhol, they executed works of astonishing formal variety, frequently at first glance totally unlike the original. | ||

| Zbigniew Władysław Solski | An Unknown Staging of The Story of Glorious Resurrection of the Lord  | 178 |

The director proposed comments on his own staging of the play by Mikołaj of Wilkowieck, shown at Easter 1983 by the State Puppet Theatre in Wałbrzych . A recollection of the socio-political context of the spectacle, and a presentation of the sources for the conceptions and inspiration of this stage vision. Z. W. Solski also indicated the supplements of the basic text and the reasons for such an operation, and went on to describe in detail one of the open-air performances. The text is followed by three appendices: Message, Staging notes and A description of the spectacle, making it possible to bring the reader close to the impact of this production in the historical conditions prevailing in the People’s Republic of Poland. | ||

| Bogusław Kierc | Out of the sack | 186 |