Issue 2005/4 (271) - Konteksty

| Wiesław Szpilka | Walking in the Tatra Mts.  | 3 |

An anthropological impression about the importance and meaning of worlds regarded as peripheral and local. Upon the basis of his own experiences, the author – a Zakopane-based ethnographer – accentuates the special quality of being here and the unique type of existential experiences associated with excursions in the Tatra Mts. In doing so, he reveals the conventional and relative meaning ascribed habitually to such concepts as the province and the centre. | ||

| Tomasz Szerszeń | Razed Warsaw , Paris n’existe plus: Images of Towns in Ruins  | 5 |

Photography as contemporary vanitas? Clearly, yes. The relation between photography and death was described not only by Roland Barthes, but also by Ralph Waldo Emerson, almost 140 years earlier... A particularly new image, especially during the nineteenth century, were the photographs of ruined towns and demolished buildings – pictures of destruction which from today’s perspective (especially that of a residents of Warsaw ) assume a special and outright ominous meaning. Ruins and a razed city (similarly to the world of the circus) are a symptom of the nineteenth-century (contemporary?) melancholic imagination. This theme appears not only in the writings of men of letters (Baudelaire, Rattier, Fournel, Kracauer...), or theoreticians (Benjamin, Simmel), but also among... doctors of medicine (Cotard). The motif of the image of a town in ruins recurs surprisingly in texts describing ravaged Warsaw and postwar reconstruction (Hertz, Zawieyski, Tyrmand). All the symptoms disclose a similar tension: old – new, the past – the future, death – life, defeat – victory, disillusion – illusion, thus corresponding to the definition of the dialectical image devised by Walter Benjamin. | ||

| Judith Okely | Visualism and the Landscape: to Look and See in Normandy. Transl. by Iwona Kurz  | 11 |

Critics of visualism, an epistemological „bias toward vision”, have focused on surveillance and overview. Taking a different perspective, this paper differentiates looking from seeing, the later being linked to all senses. Discussions of landscape appreciation in Western literature have reflected a similar restriction to the distant or privileged gaze. Theorists have rendered invisible the laborers’ and inhabitants view of landscape and the consumption of its products. Based on fieldwork and filming in Normandy , this article reinserts the biographical and the bodily meaning of landscape for unnamed cultivators and food producers, in contrast to non-labouring spectators. It also discusses how fieldwork has to confront prior images of the landscape, especially Impressionist paintings as icons which intertwine with local perspectives. Through participant observation, the anthropologist may shift from looking as spectator to seeing as participant. | ||

| Ewa Kocój | My Foe, My Friend or What Do the Rumanians See in Icons of the Last Judgment in the Churches of Bukovina?  | 23 |

An analysis of assorted sources (canonic and pseudo-canonic) of the depictions of foreign nations and confessions in icons of the Last Judgment, painted on the outer walls of Orthodox churches and monasteries in Southern Bukovina ( Rumania ). Upon the basis of her own on-the-spot research, the author described the assorted conceptions harboured by the residents of local villages. The conducted studies showed that the churches and the iconography produced their own world of cultivated collective imagery, considerably at odds with the actual details presented in the icons. This world reveals a strong connection with the history of Rumanian lands, political-national mythology, and canonic and non-canonic texts. The inhabitants of Bukovina identify the portrayed figures of the condemned with historical enemies from the East (Turks, Tartars) and the slayers of Christ (Jews), whose negative likeness is contained up to this very day in the liturgical texts of the Eastern rite Church . The depictions in the holy pictures are not always concurrent with the actual truth of the icon – the accounts of the local population are peopled with such doomed characters as Gypsies and Jehovah’s Witnesses, who actually cannot to be found in the icons. The holy pictures could, therefore, stir the imagination of the spectator to project something that is absent in reality but encountered in the texts of close culture. | ||

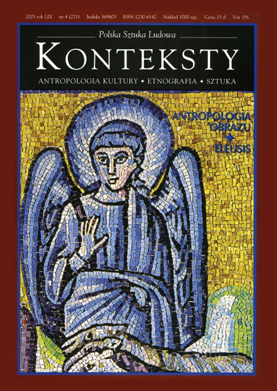

| Joanna Benedyktowicz | Opus musivum. The Ideological Programme of Sixth-Century Ravenna Mosaics upon the Example of San Vitale, San Apolinare Nuovo and San Apolinare in Classe  | 41 |

The contemporary tourist, whatever his identity, simply must become astounded and bewildered by the phenomenon of the mosaic art of Ravenna . He will be stunned, on the one hand, by its impetus and immensity and, on the other hand, by extraordinary artifice and reverence; art descriptions might be encountered in assorted writings, but only personal contact generates sincere astonishment. Aesthetic experiences become rapidly dominated by successive questions: What is the meaning of all this”? Who are the depicted figures? What is their story? What did these images signify to their contemporaries? What symbolic language did they use? Finally, what sort of questions are we unable to ask the mosaics? Is some sort of an important domain of their reality evading us due to the fact that we are incapable of making essential queries? By resorting to an extensive literature on the subject, the author analyzed the Ravenna mosaics as a historical source and a structure brimming with contents, reflecting not only the prime tendencies of the epoch of the mosaics’ origin (cultural, political, and religious), but predominantly the theological aspects. The church was envisaged as a model of the universe, a sui generis declaration of the very core of faith. Religion was not severed from public life, but indissolubly connected with it. The postulates formulated by religion at the same time reflected the civic attitude and cultural awareness. By the very nature of things, the artistic programme of churches became an instrument of politics, and since it was the most capacious element of state “propaganda”, reaching all social strata, it remained in the very centre of the interests of the emperor, especially if, as in the case of Justinian, he was concerned with the unity of his realm. Religion was to coalesce the subjects, and the church was to transmit contents reinforcing this unity. This is precisely where we should search for the sources of the phenomenon of the mosaic (opus musivum, i. e. a work pertaining to the Muses). On the one hand, as an exceptionally refined technique it fulfilled the need for opulence and pomp, while on the other hand it made it possible to turn the divine and metaphysical world into the mysterious and ambiguous language of symbols. The church as a whole became a certain model of the universe: the rather unattractive, sombre and severe architecture of the exterior concealed a magnificent and resplendent interior, which in the most palpable way possible separates the sacrum from the profanum. The layout of the interior and the decoration were governed by liturgy, which by means of the subtle language of art captured the equally rarefied theology of the period. Rays reflected and refracted against the tesserae, inclined at different angles, granted the depicted scenes and figures a luminosity that renders the spectator aware of their timeless, profound and supernatural meaning. Enclosed within the semi-darkness of the church, light possesses a theological quality as the embodiment and sign of the actual presence of God: “I am the light of the world” (John 8: 12), “God is light, and in him there is no darkness at all” (1 John 1: 5), “The light shines on in the dark, and the darkness has never quenched it” (John 1: 5). | ||

| Włodzimierz Lengauer, Leszek Kolankiewicz, Wiesław Juszczak, Krzysztof Bielawski, Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | Eleusis – a Discussion on the Book by Karl Kerényi  | 61 |

An account of a discussion held in the Institute of Art at the Polish Academy of Sciences in June 2005. The topic was Eleusis. Archetypowy obraz matki i córki (Eleusis. Archetypical Images of Mother and Daughter) written by Karl Kerenyi, an eminent expert on religion, and issued by the Homini publishing house in Cracow . The meeting involved outstanding specialists: Włodzimierz Lengauer, historian and classical philologist (author of, i. a. Religijność Starożytnych Greków [The Religiosity of Ancient Greeks]), Leszek Kolankiewicz, anthropologist of culture (and an expert on mysteries), and Wiesław Juszczak, historian of art, philosopher, and author of the much discussed book Realność bogów (The Reality of Gods). The debate was conducted by Zbigniew Benedyktowicz, editor- in-chief of Konteksty, and Krzysztof Bielawski, classical philologist and founder of the Homini publishing house. | ||

| Włodzimierz Lengauer | Eleusis  | 75 |

The Eleusis mysteries were one of the most significant phenomena in ancient Greek religion and the most prominent events in the religious life of the Athenians. The mythical interpretation ascribed the establishment of the mysteria to Demeter – a reminiscence of a meeting held by this divinity and her daughter, Kore-Persephone, abducted and married by Hades. Homer’s Hymn do Demeter, recounting the Eleusinian myth, is, however, neither a liturgical text nor are its contents theological, since in accordance with the genre it belongs to the domain of poetry; moreover, it was to be performed publicly, and thus does not betray any of the mysteries nor describes their course. The Hymn was written probably at the end of seventh century B. C. or in early sixth century B. C., i. e. an epoch in which one might seek the very beginning of the mysteria, a secret rite celebrated in a place inaccessible for the uninitiated. This was also the period (the reign of Solon) of the construction of the telesterion at Eleusis – an enclosed edifice in which the initiation rites were held. The Eleusinian mysteries, whose purpose was to guarantee the initiated a blissful afterlife, could be linked with the origin and development of Orphism, a religious doctrine about the immortality of the soul, which originated possibly during seventh century B. C. or the early sixth century B. C. Following the example of Walter Burkert, one may accept that the beginnings of this doctrine were greatly influenced by contacts with the East, particularly with Egypt . The text of a treatise about rites associated with faith in an afterlife, known today as the Derveni Papyrus, entitles us to assume that the cited and commented Orphic theogonic poem comes from precisely that period; Orphic theogony contains traces of familiarity with Egyptian and Mesopotamian beliefs. In the Athenian polis initiation into the Eleusinian mysteria played a role similar to Orphic initiation, popular elsewhere. Slightly more information about the course of the activities connected with the mysteries comes from the imperial era thanks to preserved epigraphic sources; nonetheless, these data pertain only to the organization of a procession preceding the mysteria proper, which in Eleusis lasted for three days, as well as initial preparations indispensable for participating in the Eleusinian ritual. Information provided by Christian authors (Clemens and Hippolytus) should be treated very cautiously owing to their fragmentary knowledge and biased approach. We may only conclude that the purpose of the Eleusis mysteria was to assure afterlife for the deceased who already during his lifetime believed in closer contact established with Persephone in the course of the rites. We are unable, however, to define the basis of this knowledge or what precisely transpired at Eleusis . The assumption that the ceremonies involved liturgy in the form of a chorea, including the performance of holy texts, appears to be the most probable. | ||

| Stanisław Fijałkowski | Several Questions about Constructing the Painting in the Writings of Władysław Strzemiński  | 93 |

A truly in-depth presentation of the basic elements ascribed to the concept of the painting in the writings and statements of Władysław Strzemiński, the founder of unism. An analysis of not merely the painting’s technical qualities, but also such expressive attributes as colour or light. From the viewpoint of reflections pursued during the inter-war period, the insightful and profound remarks made by Strzemiński can be compared only to those made by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz in his Nowe formy w malarstwie (New Forms in Painting). | ||

| Aleksandra Melbechowska-Luty | The Statue is a Slide, a Spiritual Phantom. Several Recollections about Myths and the Magic of Sculpture  | 97 |

The article discusses the significance of sculptures (especially statues), which for centuries have been functioning within the realm of the myth and magical thinking. Can one become fond of a statue in one’s own home? The spatial and material dimension of a statue, creating an illusion of corporeality, is the reason why in comparison with painting it remains an object alienated in the natural surrounding, a three-dimensional echo of living creatures. It can be experienced not only with sight but also with touch, thus bringing to mind a motionless, lifeless, and artificial effigy evoking the fear that it will suddenly come alive, move, speak, terrify or commit an evil deed. A contrary phenomenon was the conviction that people change into stone statues. Within the visual arts and cultural tradition we come across numerous humanized statues in assorted mythical, religious, literary and legendary sources. Adam and Eve were the first statues created by God and enlivened by His breath, while the genius of the Greeks brought to life the statues executed by Prometheus, Deukalion, Pyrrho, Dedalus, Pygmalion and Hephaestus, author of a figure of Pandora and the golden servants described in the Iliad as his helpers. During the Middle Ages holy figures were ascribed the physical features of miraculous activity – voice, motion, flowing tears or blood. Modern examples of enlivened statutes included the Statue of the Commander – the Guest of Stone punishing Don Juan, and Golem – a symbol of destructive forces. During the nineteenth century the special properties of the art of sculpture absorbed G. W. F. Hegel and his continuators, who believed that the statue is an embodied spirit (or even that it lives, thinks and feels). Sublime or extraordinary motifs associated with the ethos of sculpture were present in the Romantic and modernist theatre and literature, e. g. the works of P. Merimée ( La Vénus d’lIle), S. Wyspiański (Acropolis) and G. Meyrink. The twentieth-century cinema also introduced elements of horror connected with artificially created monsters, subsequently copied in a series of the so-called monsters of Frankenstein (inspired by the novel by Mary Shelley). Even today, uneasy feelings are stirred by the meticulously recreated figures on show in assorted waxworks, while science fiction films are full of ghastly man-shaped robots which have managed to evade human control. | ||

| Aleksander Jackowski | Within the Range of an Indescribable Art  | 109 |

The author is particularly interested in artists functioning outside the official circuit. The so-called primitive, non-professional and naive artists exist in a special niche intended for them – all traditional criteria of assessment are suspended. How is one to classify and name the oeuvre of Rząb, Okoń and Śledź. The most important related concept is expression: their works stem directly from life itself, telling the story of hardships and comprising a specific way of reacting. This expressive moment is fresh, authentic, and insufficiently understood. | ||

| Hubert Czachowski | Forms of the Spirit. Michał Kokot Talks to Hubert Czachowski  | 115 |

This interview describes the creative path followed by Michał Kokot – photographer (member of the Union of Polish Photographers), painter, poet, journalist, and social activist. The beginnings of Kokot’s artistic interests go back to his contact with small town artisans: builders of spinning wheels and blacksmiths, and a fascination with their output. Later on, he became an admirer of feature films from the 1950s. As a student of history at the Mikołaj Kopernik University in Toruń, Kokot was involved in the student art movement of the 1960s, founded the Forma photography group, made prizewinning films in the Pętla film club, and finally found himself in the celebrated Zero-61 photography group whose members included such subsequently recognized artists as Józef Robakowski, Antoni Mikołajczyk, Andrzej Różycki, and Wojciech Bruszewski. Contact with Zero-61 proved to be an introduction to the world of avant-garde contemporary art. At the end of the 1970s, after years of winning additional experiences as a press photographer, Kokot settled down in the village of Osiek near Toruń; here, he discovered authentic isolated folk artists: weavers, embroiderers, a wheelwright, sculptors and a poet, all of whom he regards as outstanding. A true animator of local art undertakings, Kokot organized a village gallery, arranges exhibitions and meetings, created a folk music ensemble, and publishes poetry. | ||

| Hubert Czachowski | 128 | |

| Janusz Barański | Anthropology – Between Pre- and Postmodernity: A Handful of Predictions for the New Century  | 130 |

An interpretation of the formula proposed by Geertz, delineating the range of anthropology – an informal logic of real life. The first part of this definition: informal logic, refers to the sphere of rationality: the principles and forms of creating human ways of life, while the second – real life, refers to its contents. Within a thus formulated scope of anthropology we tend to criticize not only the commonly held supposition but also the scientific belief in a progressing deprivation of the world of its magic properties, together with the changes occurring in successive stages of the history of culture: premodernity, modernity and postmodernity. Proof is to be found both in the range of the forms of human life and in their contents. In the first case, the crux of the matter lies in the type of rationality which from the time of Levy-Bruhl has been described as participation: the logic of the concrete, the synthetic qualities of thought as well as its situational and contentual attributes. In the second case we are dealing with cultural practices whose logical foundation is composed of rational participation. The author declares that beyond the mentioned historical-cultural divisions man makes use of logic (in contrast to the logic of science) in such spheres as magic (premodernity), ideology (modernity) or popular culture (postmodernity). More, the contemporary postmodern cultural landscape increasingly resembles its premodern predecessor, including the most recent types of magic (e. g. in politics), ritual (e. g. the stylization of life), or myth (e. g. the narratives of popular culture). In a word, even if were to admit that the commonly held view claiming that the domain of anthropology is the enchanted world, is right, then it faces a growing number of tasks. | ||

| Patrycja Cembrzyńska | The Ethnographic Surrealism of W. Hasior  | 151 |

The art of Władysław Hasior, similarly to that of many other contemporary authors, expresses a longing to find the primeval source of all civilizations, which would then serve as a foundation for constructing a universal culture. His symbol-suffused works are the outcome of ethnographic reflections about the archetypical structures that build reality. Hasior-the artist merges with Hasior-the anthropologist or, more precisely, the anthropologist-surrealist who persistently seeks traces of magic thinking in the contemporary world. By introducing into his oeuvre the practices of ethnographic surrealism, whose roots go back to Georges Bataille and the periodical Documents, and which the artist from Zakopane perfected by means of his photographic laboratory, he tried to prove the strange and curious qualities of surrounding reality, and the degree to which a growing awareness of this fact could be culturally inspiring. | ||

| Hanna Kirchner | 161 | |

| Anna Niedźwiedź | 169 | |