Issue 2008/1 (280) - Two theatres – two worlds

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | 3 | |

| *** | ||

| Michel De Certeau | Writing vs. Time: History and Anthropology in the Works of Lafitau  | 8 |

In 1724 the Jesuit Joseph-François Lafitau published Moeurs des sauvages amériquains comparée aux moeurs des premiers temps, preceded by a celebrated frontispiece. The scene selected by Lafitau depicts time and the act of writing, arranged in an enclosed space composed of the “remnants” of classical Antiquity and the savages of the New World (who are heard only as the voices of the dead, the echoes of mute Antiquity, explained by a confrontation of archaeology and ethnology). A ”person in the pose of writing” is portrayed opposite ”Time” – a bewinged old man performing the gesture of an angelic messenger. The former holds a pen with which he writes a text, and the latter – a scythe, which divests of life… The frontispiece describes the “reconstruction of history” in a laboratory: all indirectness has vanished, and there are no data to examine apart from the ”relics”. Driven away from the angels and Time, the writer is alone in his task of recreating the world from residues, including those of the Other. In other words, he is “Lazarus” – to whom Lévi-Strauss compared the ethnologist – returning from the world of the dead to the living, and equipped with incomparable knowledge incomprehensible to his contemporaries… | ||

| Roger Bastide | Le sacré sauvage  | 23 |

Sanctity constitutes a universal anthropological dimension for every religious person. Traditional socieities try to subject it to the control wielded by the community. The return to savage sanctity, which is taking place in present-day culture and European society, is linked with the deterioration of traditional religious institutions and a transferrence from organic society to an anomic one. The author compared material borrowed from the ecstatic cults of Brazil and the counterculture movement in Europe. | ||

| Jacek Jan Pawlik | The Sources, Symbolic and Meaning of the African Dance  | 32 |

The vitality of African cultures is expressed in their dance. While studying its source and the symbolic contained therein the author indicated the characteristic features of the African dance. He also recognised daily activities as the fundamental source of the dance and its determination by the place of residence, stressing the connection between the dance and the cosmology and conception of man accepted in a given community. Further on, Jacek Jan Pawlik presented the role played by the dance in the individual and social life of Africans, pointing out its essential educational, social and religious meaning. The end part of the article deals with rhythm and accompanying music. | ||

| Beata Di Biasio | The Rape of Europe and Totalitarianism. The Visualisation of the Myth of Europe in Polish Painting from the Second Half of the Twentieth Century  | 40 |

Visualisations of the rape of Europe conceived in Central- Eastern Europe during the twentieth century evoke an up-to-date version of the echoes of the antemurale ideology, unknown in the West and functioning in the historical consciousness of Central and Eastern Europe for more than 500 years. ”The average nobleman believed that by protecting the south-eastern boundaries of his state against the Tartars, Turkey or Muscovy , he was guarding Christendom as a whole”, wrote J. Tazbir. In the case of certain Polish artists the visualisation of the classical theme of the rape of Europe in Polish twentieth-century painting has been subjected to the conspicuous pressure of a specifically Polish historical-religious tradition, which transformed the classical myth of Europe into its antemurale counterpart. The presented study attempts to depict the oeuvre of Starowieyski and Hasior, inspired by the myth of Europe , against the background of European art, which often referred to this classical motif. | ||

| Jerzy Miziołek | Golgotha by Jan Styka at Forest Lawn. On the Largest Painting in the World and Its Unusual History  | 50 |

The article discusses Golgotha – an enormous painting by Jan Styka (1858-1925), considered to be the largest such composition in the world (ca 60 x 15 m ). The canvas was executed in 1896 and despite its huge size, is an outstanding work. From 1904 it was featured in the United States , and for over sixty years has been the focal point of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale , in the suburbs of Los Angeles . Its characteristic features include an interesting iconography and a history as fascinating as it is dramatic. The first part of the article considers the artist and his life: studies in Vienna and Rome , the majority of important works executed in the last decade of the nineteenth century, collaboration on once famous panoramas (such as The Raclawice Panorama) and, finally, the Parisian period in his oeuvre. Styka won international acclaim, which allowed him to own a villa and a studio in Paris and a residence on Capri (Villa Quo Vadis). The author goes on to present the dramatic story of Golgotha, which after being exhibited in Warsaw , Kiev and Moscow , was to be featured in 1904 at the world’s fair in St. Louis but never reached its destination. Attempts at transporting the canvas from New York to Paris soon encountered obstacles. Discouraged by clashes with customs officers Styka decided to leave the painting in America and never saw it again. In 1911 Golgotha was shown at the Chicago Opera House, and soon found itself in the storerooms of the Civic Opera Company in Chicago . Here, in 1943, rolled around a telegraph pole, it was discovered by Fred Hanson, an envoy of Hubert Eaton, the creator of Forest Lawn. After lengthy conservation carried out by the artist’s son, Adam Styka, and his wife Wanda, and the construction of a suitable auditorium, the painting was unveiled on Good Friday 1951, to become the greatest highlight of the Forest Lawn Memorial Park . The canvass shows a scene sometimes described as the Crucifixion but de facto depicts a moment preceding that event. A longhaired and bearded Christ with an irregular nimbus around His head, and wearing a long white robe, stands upright, gazing steadfastly at the sky and the descending wide beams of light. A ray striking Him enhances the white colour of the robe, which is almost as bright as in the scene of the Transfiguration. A centurion near-by reads the verdict from a large tablet and with his right hand points at the Christ. Almost all the witnesses of the event, including the two semi-nude thieves, the Apostles, and the Madonna are motionless, the overall impression being that some of the gathered persons and the heavens were paying homage to the Condemned in white. This scene, so very different from many other versions of the Crucifixion, takes place against the background of a sprawling panorama of Jerusalem and environs. The painter, whose preparations included three months in the City of David , painstakingly recreated Golgotha, the city, the town walls and the Temple at the time of Jesus. His earlier compositions, inspired by Sienkiewicz’s Quo vadis, served as comparative material and a context. Work on the article was facilitated by material on Jan Styka collected in the Workshop for the Dictionary of Polish Artists in the Institute of Art at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. | ||

| *** | ||

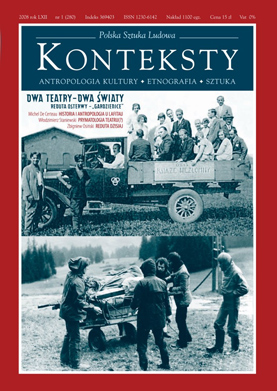

| Ireneusz Guszpit, Dariusz Kosiński | Two Theatres – Two Worlds  | 61 |

A major part of this issue of ”Konteksty” contains the outcome of a scientific conference ”Two theatres – two worlds”, held on 10-12 May 2007 at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow. Its initiator and author of the fundamental idea of combining reflections on the accomplishments of the Reduta Theatre and the Centre for Theatre Practices ”Gardzienice” was Ireneusz Guszpit, and the session was organised jointly as part of the Theatrical Writings of Juliusz Osterwa research project financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Prominent assistance was rendered by two academic centres: the Department of the Theory of Culture and the Performing Arts in the Institute of Polish Philology at Wroclaw University and the Chair of Drama in the Polish Philology Faculty at the Jagiellonian University . A fitting occasion for such a double meeting was provided by two anniversaries: the sixtieth anniversary of the death of Juliusz Osterwa (19 May 2007) and the thirtieth anniversary of ”Gardzienice”. Such a blend of death and life may appear just as accidental as it is hazardous, but we are convinced that it reflects the basic principle of the continuum of tradition, in whose current the work of the two theatres progressed, and continues to do, and their worlds were created. The death of Osterwa, which, after all, ended the history of the Reduta Theatre, did not denote the end of the ideas, which he, Mieczysław Limanowski, and artists co-working with them attempted to implement. These ideas are to be found, interpreted and unravelled in their own ways in, i. a. the praxis and philosophy of ”Gardzienice. Real life does not come to a close but goes on – albeit transformed. It was our intention to ponder on the force guaranteeing this continuum and the changes causing the constant rejuvenation of tradition together with our invited guests – eminent experts on the two theatres, as well as their students: young researchers, members of a successive generation whose attentive presence and deliberations will (hopefully) accompany future transformations and study past ones. We have been fortunate in assembling almost all the most important researchers willing to tackle the heritage of the Reduta Theatre and the achievements of ”Gardzienice”. Regrettably, not all are represented in the material published in this issue of ”Konteksty”. For assorted reasons we have not included texts by Zbigniew Osiński, Leszek Kolankiewicz, Zbigniew Taranienko and Jarosław Fret, and technical obstacles have made it impossible to add the important statement by Włodzimierz Staniewski, who despite myriad tasks agreed to take part in our conference. Despite these gaps, we believe that the enclosed material vividly depicts a feature with which were are concerned the most: the distinctiveness of this particular line of the Polish theatre whose important highlights are the Reduta and ”Gardzienice”, which comprises a symptom of a holistic approach to culture, and which possesses such close (although sometimes perhaps dangerous) links with anthropology. Within this tradition, the theatre is not a tool and place for the production of works of art – luxurious commodities, but constitutes a space for studying the individual and the community by ever renewed experiments and tests, whose outcome is the truth found in answers to fundamental questions. Expressing our gratitude tot the editors of ”Konteksty”, which from the celebrated theatrical issue from 1991 consistently co-creates a field of reflections merging theatre and cultural studies, for proposing the publication of the post-conference material, we take the liberty of hoping that these texts will become a strong link in the chain of regularly rekindled anthropological-theatrological reflection. | ||

| Maria Osterwa-Czekaj | An Emotional Gloss | 62 |

| Ireneusz Guszpit | Two Theatres – Two Worlds: Day One  | 63 |

A presentation of the origin of Juliusz Osterwa’s Reduta Theatre and Włodzimierz Staniewski’s ”Gardzienice”, closely connected with accompanying historical circumstances. In the case of the Reduta Theatre, founded in 1919, they involved the shaping of the renascent Polish state, and for “Gardzienice” – an attempt at seeking refuge from the absurdity of real socialism during the end stage of the Gierek era. The name of Osterwa’s theatre referred to its seat (the Ball Rooms at the Wielki Theatre in Warsaw ), the tradition of entertainment, and a bastion – a redoubt fort system. Facts from the history of the struggle for a new Poland are thus accompanied by those from the struggle for a new theatre. ”Gardzienice” dates back to 1977. The universally accepted symbolic date of its origin is St. John’s Eve (24 June), a pagan festivity, and the eve of the celebrations of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (15 August), derived from folk tradition. The political, manners and morals, and even weather information acquired from the press of the period shows how the ideas of artistic visionaries are born in the hubbub of daily life. | ||

| Jan Ciechowicz | The Travelling Theatre  | 69 |

For persons of the twentieth century a journey becomes one of the most important spiritual experiences, the achievement of self-knowledge. The same holds true for the man of the theatre. The author compares two experiences of ”the travelling theatre”: the Reduta Theatre (”The Itinerant Reduta”) of the 1920s and the “Gardzienice” Theatre Association more than fifty years later. The journeys made by the Reduta Theatre along the Eastern Borderlands were conceived as a large-scale undertaking, but lacked extensive descriptions: their most interesting testimony are letters written by Bronisław Nycz, a student of Polish philology, to his fiancee. On the other hand, the rural wanderings of Staniewski’s group were from the very onset carried out in the company of researchers: Osiński, Kolankiewicz, Morawiec, Pawluczuk, Burzyński, Guszpit..., who discovered not only Bakhtinean inspiration but also the notion of ensemble work, pursued at the Reduta Theatre. The expeditions themselves became something more than mere ”wandering”: a way of life, a process of submerging oneself in reality, a return to the sources and literal qualities, achieved via the theatre and outside its range. | ||

| Wojciech Dudzik | What Has ”Gardzienice” Taught Me  | 73 |

This sketch compares the activities of the theatres discussed at the Cracow conference on ”Two theatres – two worlds”: the Reduta Theatre and ”Gardzienice”. The title refers to a statement made in 1925 by Stefan Jaracz, a former Reduta actor: What Has the Reduta Taught Me. The first part of the text asserts that Jaracz’s concise characteristic of the interwar Reduta can be considered as apt also in the case of ”Gardzienice”. Both companies attempted to establish a self-reliant theatre, taught how to work, created their own methods, established art laboratories, introduced musical spectacles, and featured actors who subsequently cultivated new methods of theatrical work; the two theatres also organised journeys (expeditions) to the Eastern Borderlands of the Republic. In other words, they were not merely artistic institutions but also social and educational initiatives (in addition, the Reduta had its own Institute, and ”Gardzienice” – an Academy of Theatre Practices ). In a further part of the sketch the author evokes his personal experiences and contacts with ”Gardzienice” which convinced him that Włodzimierz Staniewski creates the most rapid theatre in the world (the spectacles are brief, extremely intensive and brimming with meanings difficult to decipher after seeing a single show), that work on a ”Gardzienice” spectacle never ceases (each is slightly different, thus rendering theatrological reconstruction extremely difficult), and, finally, that a theatre does not exist to be understood – it is there to offer the spectator poignant experience. | ||

| Henryk Izydor Rogacki | Osterwa of the Skamandryci  | 78 |

A register and description of the image of Juliusz Osterwa and the Reduta Theatre in the lyrics, publicistics and discursive as well as artistic prose by the Great Four of the Skamander group: Tuwim, Lechoń, Wierzyński, and Iwaszkiewicz. The author encloses a chronological presentation of the cooperation and animosities between the Skamandryci (members of the group) and the Reduta. The text attaches great attention to the evidence provided by poetry, and proposes a reinterpretation of the assumption that the Skamandryci had created the “black legend” of the Reduta. The author also stresses the mutual fascination of the poets and the avantgarde theatre, which, naturally, did not exclude polemics and even hostility. This enchantment via negation is explained by the Skamandryci’s attachment to the model of the theatre of their childhood and youth, based on the myth of the actor. One of the authors of this myth’s allure was Osterwa – a star specialising in the parts of lovers, who later tried to become a theatrical artist and even to transcend the theatre via the theatre by entering the category of existence. The case of Osterwa and the Skamandryci appears to be an exception confirming the rule that memory about historical facts is ”created by the poets”. | ||

| Joanna Eliza Pawelczyk | Mieczysław Limanowski – the Precursor of the ” Cultural Forefathers’ Eve”  | 84 |

The sketch deals with the significance of Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve for Mieczysław Limanowski, the co-founder of the Reduta Theatre. The text is based on research into Limanowski’s notes in the archive of the Museum of the Earth at the Polish Academy of Sciences, carried out by the author under the guidance of Prof. Zbigniew Osiński. An attempt at supplementing a project by Leszek Kolankiewicz on the interpretation of Polish culture via Forefather’s Eve (a dialogue with the dead) by considering the conceptions launched by Mieczysław Limanowski. | ||

| Katarzyna Regulska | The Reduta and Vieux Colombier  | 90 |

The origin of the Reduta Theatre and Vieux Colombier is part of the current of the reform of the theatre at the turn of the nineteenth century. This sudden upheaval and appearance of new ideas, together with an attempt at extracting the theatre from the state of inertia into which it had been thrust by the nineteenth century, undoubtedly exerted an enormous impact on Osterwa, Limanowski or Copeau. At the same time, all three transcended the domain of the aesthetic quest conducted by the First Theatre Reform by granting the focal point to the actor conceived as an artist of the theatre. By conducting a search within the art of acting they continued the work of the first theatrical laboratory – the Moscow Art Theatre , founded in 1898 by Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko. The three authors concentrated their efforts on freeing the actor from the routine of his profession. They contrasted ensemble work with the star system, the agility of the mind and the body with rigidity and the recreation of clichés, and activity with recitation. The theatre is not entertainment but a challenge and a service. By choosing the shortest path towards fame, the actor has narrowed his horizons and deformed his profession. Osterwa, Limanowski and Copeau required predominantly people pursuing a passion, true lovers of the theatre – amateurs. One could say that they wished to train future professionals-amateurs, envisaging these paradoxical combinations as the sole guarantor of genuine change. | ||

| Wanda Świątkowska | “Each Shakespearean adaptation brings about a disputation” – Juliusz Osterwa’s Hamlet  | 95 |

In this article, the author presents Osterwa’s paraphrase of Shakespeare’s tragedy in the context of other Polish adaptations and translations. The essay outlines Osterwa’s approach to Shakespeare’s most famous drama and explains the artistic decisions which led to this particular interpretation of the history of Danish Prince. The founding father of the Reduta theatre wrote his adaptation in 1940, a time of crisis for the nation and in his personal life. Osterwa’s interpretation was strongly influenced not only by the harsh realities of the time but also by his innovative theatrical ideas, which were then just beginning to crystallize. Shakespeare’s Prince of Denmark is transformed into a Polish Prince of wartime. Osterwa presents him as an example of one attitude to action and war which a human being can choose in such times (the contrast to Hamlet’s position being those of Antigone, Bolesław the Bold in Stanisław Wyspiański’s drama and the Constant Prince in Juliusz Słowacki’s tragedy). Moreover, Osterwa criticizes the hesitancy and immaturity of Shakespeare’s Prince, concluding that there was no room for “Hamlets” in 1940. The Hamlet of Osterwa’s adaptation is reaching maturity and preparing to face his destiny and, ultimately, his own death. Such an interpretation derives from Osterwa placing the plot in the context of Polish literature (he makes use of Wyspiański’s translations of Hamlet’s monologues and incorporates some poetical extracts from his Study of Hamlet) and Polish reality (for example, by ‘polonising’ the setting, the characters and the language, using quotations from Polish literature, proverbs or colloquial Polish). All this gives Osterwa’s work its sense of innovation and creates an entirely new interpretation of Shakespeare’s tragedy. | ||

| Tadeusz Kornaś | The Expeditions of Constantin Stanislavsky and Włodzimierz Staniewski  | 101 |

The inclusion of the Moscow Art Theatre (MKhAT) and the Centre for Theatre Practices ”Gardzienice” into a current of joint artistic tradition poses a difficult task. The activity of Constantin Stanislavsky and Włodzimierz Staniewski is separated by an enormous time difference – almost a century (which for the theatre coincided with an age of basic transformations). The aesthetic dissimilarity of the spectacles and ethos of the two theatres does not favour proposing any sort of a parallel associated with mutual impact on artistic undertakings (naturally, in this particular case such influence could follow only one direction). Nonetheless, the article attempts to compare some of the artistic and research initiatives (connected with travels) conducted by Constantin Stanislavsky and Włodzimierz Staniewski in view of the fact that at times they were strikingly similar, and in certain instances outright identical, despite the different consequences derived by the two men. Apparently, Stanislavsky longed to work in the countryside (which he described in My Life in Art), in conditions similar to those enjoyed by the Centre for Theatre Practices ”Gardzienice”. The Moscow Art Theatre (and its studios) embarked upon expeditions into the distant province, and its spectacles made use of the songs, gestures, objects and costumes discovered in their course of these journeys … The Stanislavsky theatre organised also other ventures comparable to the ”Gardzienice” Gatherings, when village residents, folk artists, displayed their skills in the seat of the theatre. More, Stanislavsky tried to examine the extent to which his ”naturalistic” spectacles could exist in natural space (for instance, a park). Finally, both Stanislavsky (together with Sulerzhitsky) and Staniewski formulated exceedingly radical theatrical utopias connected with travelling and abandoning the traditionally conceived theatre. | ||

| Alicja Mańkowska | The Path Towards Discovering Meaning in the Melting Pot of Cultures  | 108 |

The author evokes philosophers (including Jacques Derrida, Zygmunt Bauman, Martin Heidegger, and Michael Foucault), who while creating their intellectual systems tried to diagnose the condition of the post-Cartesian man torn between spirituality and corporeality, and submerged in endless discourse. She goes on to point out the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche and George Bataille as well as Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of the grotesque. All these thinkers stressed the possibility of rediscovering the path towards metaphysics and freedom. The ”Gardzienice” Theatre applied the grotesque in order to skilfully create a distance towards surrounding cultural excess. By annexing assorted beliefs and styles merged with ribald laughter it tried to provoke the collapse of the conscience, and by resorting to unadorned culture – to encourage a return to the primeval world of human spirituality. Friedrich Nietzsche indicated the moment of the fall of the tragedy as a time initiating the process of ridding the myth of all transcendence. Within this context the ”Gardzienice” spectacles endeavour, by creating a new type of drama, to generate an equally new mythical domain. In Bóg Nizyński (God Nijinsky) the Wierszalin Theatre portrays the tragedy of a demented genius. As a post-Cartesian creature he experiences and believes in spiritual-corporeal unity and the cathartic might of the Absolute – the price is insanity. The contemporary anthropological theatre tries to discover meaning within a melting pot of assorted cultures. It is incapable, however, of reviving the old myths, since it is possesses the awareness and experience of post-modern dispersion. It attempts to build a horizon of senses based on a new myth, whose hero is man in the act of becoming, rent between insanity and recollections of sanctity. This moment of transgression can be grasped thanks to the distance emerging from the grotesque. | ||

| Monika Białecka | From Counterculture to the Alternative – for Those Who Find the Church Inadequate  | 113 |

The introduction evokes the historical and sociological foundations of phenomena known as counterculture and the alternative, which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s on a worldwide scale; special emphasis has been placed on their political sources also in Poland . The main part of the article recalls five spectacles staged by the Polish students’ theatre in 1970-1980: Spadanie (Falling) at the STU Theatre (1970), Koło czy tryptyk (Circle or Triptych) at the ” 77” Theatre (1971), Jednym tchem (In a Single Breath) at the Theatre of the Eighth Day (1971), Exodus at the STU Theatre (1974) and Odzyskać przepłakane lata (To Regain the Mourned Years) at the ”Jedynka” Theatre (1980). The descriptions of the stages and the commentaries are a mosaic of quotations from studies by Aldona Jawłowska, Sławomir Magala, Konstanty Puzyna, and Tadeusz Nyczek, four leading Polish authors writing about the alternative movement generation. | ||

| Małgorzata Dziewulska | Up to the Eyes  | 120 |

The author deliberates on the post-modern origin of a phenomenon, which she describes as ”the Gardzienice prophecy” (and which she regards as extremely complex and, consequently, with rather unclear components). For the purposes of a ”Baudelairean” analysis of photographs from past Expeditions she tests the instruments created by Barthes in La chamber claire (e. g. the punctum, the antidotum). On the other hand, the author considers the description of the road to Gardzienice from Andrzej Stasiuk’s Mokry grudzień (Wet December) to be the most magnificent revelation of the poetic rift. It affects the very essence of the original ”Gardzienice” visual dramaturgy, and provides more perfect expression to the essence of poetic activity, ”the passage of emptiness”. The author proposes this image as the theme of reflections instead of the no longer topical vision of ”Gardzienice” perceived within the context of the former political system. | ||

| Dariusz Kosiński | The Theatre in the Spirit of Music – the river of Gardzienice.  | 124 |

In this essay the author tries to outline the stream of Polish theatre tradition to which – as he is convinced – the “Gardzienice” theatre not only belongs, but also constitutes. This, as the author calls it, “Polish theatre of musicality” was initiated by Adam Mickiewicz both in hist masterpiece – The Forefathers’ Eve, and in his original philosophy of the “tone” – specific value of musicality present not only in melody or rhythm, but also in human words, actions, landscapes and so on. The practice of creating theatre not from the texts and meanings, but from music and actions, of not writing for and on the stage, but composing a live event like a musical piece, was present in the works of Stanisław Wyspiański, ideas and experiments of The Reduta theatre and performances by Jerzy Grotowski. But it was Włodzimierz Staniewski and his company of Gardzienice, who regarded the idea and practice of musicality as the core of their work, developing new methods of creation and training. Being the heir of the tradition, in specific way summarising it, Gardzienice also gave birth to some new attempts and experiments, run by former members of the company. Thanks to it “the theatre of musicality” can be seen as one of the most important and strongest streams of contemporary Polish theatre. | ||

| Małgorzata Jabłońska | Dramaturgy of the Body. An Outline of a Research Project upon the Example of an Analysis of Spinal Training at the Centre for Theatre Practices ”Gardzienice”  | 129 |

Recognition of dissimilarity in acting technique of OPT “Gardzienice” as a result of unique body formation (gardzienice body), which is a product of the long lasting training, is starting point of this paper. The dissimilarity reaches not only body formation but also performance composition built on physical activity and nonverbal signs, which become actual performance’s message. Undertaken research perspective includes description of three levels of performer’s physical existence in receiver’s perception: biological (performer’s bíos), esthetical, iconic, which allows in the future to effectuate the performance analysis from the angle of corporal acts dramaturgy. This paper is focused on biological level – performer’s bios. The body-use method of description based on Eugenio Barba’s theatre anthropology sets forth the image of gardzienice body (as variant of performer’s bíos) and its meanings in performer and receiver perspective. The most recognisable elements of body formation on a biological level are: extraordinary absorption and exaggerated movement of spinal column, leading the movement out of loins, collective short distance movement synchronised by audible breathing, great frequency of tactile contact. They are the result of musicality and mutuality – the main principles of Gardzienice’s training – executed in practice and reflected in existing of distinctive body practices such as: position of compact energy, group acrobatics, night running. Main meanings of performer’s body formation which are: eroticism, risk, commitment, are, usually unconsciously, recognised and by means of emotional empathy and metakinesthesia evoke physiological response in receiver’s body. As reflection of theatre work ethos they also force receiver to revaluate one’s own existential attitude. | ||

| Jadwiga M. Rodowicz | “Gardzienice Exercises” and Certain Aspects of the Form Kata in the Tradition of the Martial Arts and Spectacles in Japan  | 136 |

A first confrontation of the “Gardzienice” training system, applied in natural conditions, with the system of spiritual exercises and practices in Japanese tradition. To a certain degree the text is a continuation of the article Przywrócone pokrewieństwo (Restored Affinity), published in “Didaskalia”, no. 71 (2006). | ||

| Włodzimierz Staniewski | The Primatology of the Theatre?  | 143 |

”Sometimes we become hypnotised by a verbal construction. There is, for example, something seductive in the concept of the ’primatology of the theatre’. I find myself attracted by this neologism, and the chance to make wider use of the term ‘primatology’, outside the established biological connotation. Traditionally, all problems connected with man are excluded from primatology, since they are the domains of anthropology. The criteria, however, remain blurred. Some primatologists claim that the anthropoidal species belong to the hominids. That which is primary, rudimentary and substantial in the articulation of man’s ancestor testifies not only about the power of expression but also about the forms of the expression of the homo sapiens, such as laughter, which Dostoevsky declared is the most profound characterisation of the properties of the human being. Purportedly, certain animals are also capable of laughing. One could say that we are concerned with the ‘simplicity formula’ (cf. Hidden Territories), i. e. the behaviour and games that remain in the closest possible homeostasis with the natural environment. In the most recent issue of ”Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” (USA) American scientists propose the thesis that ‘at the beginning there was the gesture and not the word’ ”, Włodzimierz Staniewski wrote on the idea of the primatology of the theatre, associated with the experiences and impressions derived from his latest trip to India. | ||

| Zbigniew Osiński | The Reduta Today  | 148 |

The Reduta Company and Institute under Juliusz Osterwa and Mieczysław Limanowski was one of the first Polish cultural centres (in the present-day meaning of the term), which acted as a theatre; its status was a source of inspiration both for the Centre and others. Throughout the Cracow conference I intensively experienced the presence of the now defunct Laboratory Theatre of Jerzy Grotowski, which in 1966 took over the Reduta emblem; the same year also marked the inauguration of its live tradition. In recent years, Polish researchers have frequently identified and replaced the ecumenism of the Reduta, comprehended as widely as possible, with Catholicism. I am firmly convinced that this approach is the consequence of cognitive reductionism. Otherwise, how are we to explain the presence in the Reduta Company and Institute people of other dominations and non-practising Catholics? The Reduta was an ideological theatre due to its premises and conscious choice. Its founding fathers consistently stressed that the company’s activity was based on the idea of the inimitable ”Reduta quality”. Tadeusz Kornaś, the author of a review of my book: Pamięć Reduty. Osterwa, Limanowski, Grotowski (Memories of the Reduta. Osterwa, Limanowski, Grotowski), wrote: “ [...] My avid attention was drawn to a list of the names of the representatives of the Reduta [...]. Since the Reduta posters did not mention names, many actors and apprentices would have remained totally unknown. Numerous young Reduta actors died during the war. I read the list as if it was a roll call, a recollection of those who have passed away, in other words, in a highly personal manner”. I have taken the liberty of enjoying the hospitality of the editors of “Konteksty” and have supplemented, and in several places, amended the list. | ||

| Katia Michajłowa | A Semantic Characteristic of the Singing Vagrant  | 157 |

The article deals with main features of sign characteristics of the wandering singer-beggar among the Slavs, which trace his semantic differences both from other wandering professional singers and from the ordinary beggar. Blindness is one of his main features. This infirmity is seen as: a sign of another world, of world beyond, of death (in the sense of death for the earthly affairs; as lack of knowledge about ‘our world’ and knowledge about the world beyond); as a sign of prophecy, knowledge and wisdom, a sign of concentration in the inner life, of a more developed spiritual activity, a higher morality and better intuition; a connection with music and the divine; predestination for the art of singing. The author reveals differentiated attitude of peasants towards the blind singer-beggar and the ordinary beggar, and stresses that this is due to the enhanced sacrality of the former. The power of the blind singer-beggar’s blessing and curse is underlined. In the paper is made detailed analyses of the function of the singer- beggar in important rites of passage in the life of the patriarchal community – wedding, christening of a new-born baby, funeral and commemoration rituals. The semantic content of his clothing and accessories is analysed with a special attention to his stringed musical instrument and the melody of religious-legendary songs. | ||

| Aleksandra Melbechowska-Luty | The Imaginary World of Jerzy Markiewicz  | 170 |

Jerzy Markiewicz (1928-2003) was an amateur artist and a self-taught professional. He studied in the Department of Farm Mechanization at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, but his passion for art predominated. Markiewicz was a greatly talented man of imagination, creative vigour, and special sensitivity. The author of ceramic bas-reliefs and figures with a synthetic, cohesive form and rounded surface, he also illustrated children’s book, either his own or those by other authors, and carved decorative compositions made up of numerous small figures (The Circus, Noah’s Arc). In about 1898 Markiewicz decided to concentrate on oil painting, producing fantastic depictions of people and animals in unreal landscapes. He also tested his skills as the author of posters and executed kinetic sculptures entitled Birds and Kites. His works were shown in Warsaw , Poznań , Sofia , Brno , London , Spain and Japan . As the editor of agricultural periodicals he often travelled all over Poland and always remained close to rural life, reflected in his oeuvre. In 1971- 1972 Markiewicz designed a larch house in the village of Kikoły , built by highlanders from the Spisz region and roofers from the Suwalki region, and outfitted it with hand-made appliances, utensils, paintings and drawings. Suffering from a serious heart condition, he spent the last years of his life painting a frieze telling the story of the passage of time, and constructed a three-dimensional composition The Eye of Providence in six scenes. | ||

| Kornela Binicewicz | 177 | |