Issue 2013/2 (301) -

| Paweł Próchniak | Lublin: a Contribution to the Topology of a Palimpsest  | 5 |

This sketch is an attempt at a description and semiotic interpretation of a structure created by mutually permeating texts in the spirit of a palimpsest, with a keystone in the form of the Seer from Lublin and the town of Lublin as such. The overlapping texts include, i.a. Chassidic stories about the Seer, the “Chassidic chronicle” Gog and Magog by Martin Buber, the essay Oko cadyka by Władysław Panas, poetic identifications by Józef Czechowicz, the topography of the non-existant Jewish district in Lublin, figures of absence in the town’s substance, curious manifestations of non-existence, traces of the touch of radical evil. The texts constitute a story that emerges in an empty space in the wake of another space (replacing silent emptiness), filling it with the real presence of “writing” and ensuing reading (a form of reading the world and a lesson of existence). The semiotic potential of this tale – focused especially in Oko cadyka – is the prime object and canvas of reflections about Lublin, presented in the sketch as a semiotic continuum spanning from a concrete place in the topography of the town to domains indicated by the mystic intuitions of the Seer. | ||

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | Aleja Róż and its Environs | 11 |

| Jan Gondowicz | The Locative Case  | 43 |

The sphere of memory encompasses several streets in Mokotów, a peripheral district of Warsaw. The range of reminiscences dating back to 1954 stretches from the author’s house and embraces the slow transformations of the district’s villa character due to its gentrification. This is what happens when someone’s domesticated space turns into a commodity. | ||

| Piotr Jakub Fereński | Breslau Central. Train Station Scenes  | 47 |

The author postulates the need for pursing within the humanities something that Gaston Bachelard described as “topoanalysis”, deliberating on the imagery and ways of experiencing transit space. He delved into this problem within the context of recurring theses about non-enrootment, the deprivation of identity, and the uniformisation of places (or non-places) in the era of modernity. Take the example of the Wrocław train station, its distant past and contemporary history. | ||

| Walentyna Krupowies | Two Opinions about Wilno. The Town of Miłosz and Venclova  | 53 |

The axis of the article is an interpretation of a conversation about Wilno (Vilnius) conducted by Czesław Miłosz and Tomas Venclova, subsequently published in “Kultura” in 1979. Two aspects of this dialogue are particularly interesting and clearly outline the co-dependence of subject and space. There occurs an autobiographisation of Wilno: the participants perceived the town via their lives marked by twentieth-century history. The subject becomes localised: the space of the town co-shaped his identity. Wilno is seen as endowed with a great conflict-prone potential. The way of speaking about Wilno proposed by both poets turns it into an agora, i.e. a place suitable for an exchange of thoughts, views and ideas. | ||

| Beata Kopacka | The Zoological Garden. Topics and Significance  | 61 |

An article about the zoological garden as a cultural fact (historically moulded and with characteristic semiotic features) – an element of urban space reproducing mythical motifs and contents. | ||

| Peryferie, marginesy | ||

| Magdalena Zych | Allotments, the Edges of the Landscape  | 65 |

The edges of European towns are often filled with conspicuously present allotments. The text draws attention to their extreme character in the geographical, aesthetic and existential meaning of the term. By evoking examples from Marseilles, London, Vienna and Cracow the author discussed allotments as a manner of residing in the landscape in contrast to its common visual consumption. The conclusions presented in the article were preceded by research conducted at the Ethnographic Museum in Cracow in 2009-2012 by a team of twenty researchers (including anthropologists, sociologists, historians of art, and ethnobotanists) in Cracow, Katowice, and Wrocław. The research project, known as “work-allotment”, ended with an exhibition and a publication of the out-come of the work performed by the team: a copious book bearing the same title. | ||

| Kuba Szpilka | Peripheral Centre. Panoramas of the Tatra Mts.  | 71 |

The Tatra Mts. and their world at the onset of the twenty first century comprise a dense and vital net-work between the dimensions of historical existence (described by the French historian Fernand Braudel as longue durée structures, upturns and events). It is difficult to find on a map of Polish culture a place equally provincial and short-lived, about which so much has been written and which possesses such a copious iconography. The belles letrres, scientific writings, re-collections, the visual arts, architectural visions and realisations, photography, the cinema and music have recorded an intensive phenomenon endowed with extraordinary magnetism – the Tatra Mts., the town of Zakopane, and people circulating within Nature and Civilisation, comprehending, interpreting and designing. This event emerged unexpectedly in the last decades of the nineteenth century and is rapidly gaining assorted meanings. | ||

| Piotr Mazik | Traces of Atlantis  | 75 |

Quite possibly the number of recollections concerning the Tatra Mts. is simply too large. Their over-whelming majority is based on the obvious convention of presenting universally familiar landscapes captured decades ago or a documentation of elements of essential importance for our space, such as the opening of a hostel, sports competitions, a cultural event. The Tatra Mts. Atlantis is the outcome of an excess of observations of such depictions, which result in compressing the portrayals of the Tatra Mts. and Zakopane. An attempt at taking a look from the outside makes it possible to arrange unexpected collections, whose examination may come as a surprise. A non-extant ski lift on Mt. Łopata Kondracka, a tiny hut on Miętusi Saddle, a miniature meteorological observatory on Żółta Pass, the first hostel in Wielicka Valley, Mt. Giewont without the cross, Goryczkowy Cirque without the ski lift and featuring only traces of skis, the disassembled “Chatka Ascety” climbers’ wintertime camp on Włosienica Glade, a valley deprived of trees… A lost land – the Tatra Mts. Atlantis. | ||

| Monika Sznajderman | Memory Gaps. A Family History  | 79 |

By taking a careful look at a series of pre-war photographs the author conducted a fragmentary albeit emotionally condensed reconstruction of the history of her father’s family. As a representative of the Holocaust second generation she is a carrier of post-memory – incomplete, intermediated, “full of holes”. The point of departure for the history of the Sznajderman family is a villa in Miedzeszyn – once the vibrant “Zacisze” guesthouse and today a non-place overgrown with trees, forgotten, and in no way betraying its history. | ||

| Aleksandra Janus | The Filling of Emptiness. A Museum and the Paradox of Remembrance  | 89 |

The Jewish Museum in Berlin designed by Daniel Libeskind is sometimes treated as an example of counter-memorial architecture. According to James E. Young, the author of the term, the counter-monument is to be an answer to the challenge of creating memorial representations of the Holocaust: its task is chiefly to commemorate the absence of the victims and the void left behind by them in such a way so that obliteration would become impossible. More, the counter--monument is to become a space of remembrance de-signed so as to challenge the very idea of a monument and well-worn strategies of remembrance. The negative field of reference for the conception of the counter-monument consists predominantly of all monuments erected to commemorate the events of both world wars. The Jewish Museum in Berlin certainly eradicates boundaries between the traditionally comprehended museum and the monument although the monumental building designed by Libeskind appears to be at odds with numerous postulates of the counter-monument qualities defined by Young. By referring to other examples of counter-memorial architecture, the conception proposed by Young and texts criticising it, the presented article attempts to demonstrate that by creating a monumental representation of the plight of the German Jews and by trying to include emptiness, silence and absence in the architectural construction of the building Libeskind produced a closed, complete, and finite museum monument rather than a counter-monument. | ||

| Roma Sendyka | Robinson in the Non-places of Memory  | 98 |

Non-places of memory are objects from the “margins of the Holocaust” and, more extensively, places potentially typical for Central Europe, connected with the massacre, burial, and disrupted lives of the victims of twentieth-century genocide; indicated by Claude Lanzmann as empty and unmarked spaces calling for commemoration they do not have a typology or a stabilised name of their own. Places-phantoms? Places-utopias? Simply – evil places? In an analysis conducted by Georges Didi-Huberman they become places of essential meaning, malgré tout, which could be deciphered as a call for an in-depth analysis of those small, scattered objects whose space today combines death and life, the human and the inhuman, memory and oblivion, the past and the present. | ||

| Maciej Krupa | “Pepita”, “Łada”, “Palace”. Salon, Torture Cell, Spa  | 105 |

An attempted examination of a single concrete place/non-place in Zakopane, whose history depicts the structure of the town as a palimpsest. Once upon a time this was the site of the “Łada” villa belonging to the Żuławski family, a salon important not only on a local scale but also on a national one. “Łada” was consumed by fire and replaced by the “Palace” modern guest house, which during the occupation was the seat of the Gestapo and became known as the “torture cell of the Podhale region”. Today, the building, bearing the same name, is advertised as a “sport, spa & wellness” centre. Site, memory and identity, and in the background: Symphony No. 3 by Henryk Mikołaj Górecki. | ||

| Dariusz Czaja | Venice. Tectonics of a Non-place  | 113 |

Rovigo and Venice are two localities in the Italian region of Veneto, situated several score kilometres apart. Rovigo does not feature tourist attractions and is absent on the map of travellers, while Venice, the town-monument, is an archetypical “place to visit”, described in detail in every guidebook. It would appear that Rovigo is a typical non-place on the borderline of non-existence, while Venice is a “place” firmly ensconced in the mythical geography of Italy and Europe. The author diametrically reversed all signs and demonstrated the non-obvious nature of such routine classification. By referring to texts about the two towns (Herbert – Rovigo; Agamben – Venice) he disclosed their unknown aspects and the dialectical place-non-place dimension. Rovigo turns out to be a genuine place, while Venice is phantom reality. | ||

| Magdalena Barbaruk | Another La Mancha? The Toponimics of La Mancha  | 131 |

Reflections on assorted embodiments of La Mancha led the author to defining it as a “place of the wanderer” and determining the reasons for transition and the assumption of new names as cultural. The article draws attention predominantly to geographical and historical indeterminism in describing a given place as the course of the wanderings of Don Quixote. The “mobility” of La Mancha is associated with treating it as axiotic space associated with Don Quixote-derived values. The article considers assorted domains of the “otherness” of La Mancha. | ||

| Justyna Chmielewska | Istanbul and Its Wounds  | 139 |

The autor focuses on two neighborhoods: Tarlabasi and Sulukule, some of the poorest, most obsolete and entropic spaces in Istanbul. Both areas have recently undergone a process of a somewhat brutal urban transformation, during which those slums and ethnic minority ghettos (first inhabited predominantly by Gypsies, second by Kurds) have been transformed into luxurious upper-middle-class residencial areas. This process of rapid and forced gentrification is interpreted as a way of “curing” a specific urban “disease”, that has long ago infected the “body” of the centuries-old metropolis. | ||

| Marta Miskowiec | It Is / It Is Not  | 151 |

The text is about Galicia, with the author asking whether talking about Galicia is exclusively part of nostalgic reminiscences? Absence on a map does not denote absence as such. The myth of Galicia is maintained and exploited mainly by reminiscences of the Eastern Borderlands. Legends about Emperor Franz Joseph and stories about the imperial army appear to be facing extinction but nothing seems to threaten family sagas. The eulogists of the Borderlands or the “empire” have created a distinctive likeness of Galicia and have their mythologised pilgrimage designations, but not all is obvious and closed once and for all. | ||

| Piotr Seweryn Rosół | Imprisoned on a Journey to No-where. Idiotic Stories by Andrzej Stasiuk  | 157 |

The Slavonic “on the road” by Andrzej Stasiuk does not end in Babadag or some forgotten but desired “elsewhere”, while chaotic wanderings confront the protagonist with the incomprehensible and the unpredictable, and the text does not aim at any sort of a legible finale; more, it remains imprisoned, just like its subject, on a journey to nowhere, a nonsensical roving, an incessant va-et-vient from signifiant to signifié (and back again), an eternal “between”, on the road. It does not seduce with invisible excess but disturbs with a visible lack. The titular On the road instantly reveals the pornographic and not hermeneutic character of the travelogue, and right way – and after the dispersion of the grand narratives this appears to be totally comprehensible – prefers the Road, the Process, and Motion to Destination, Realisation and the Finale, and thus intimate reading to programmed deciphering, geography to work performed by memory, and memory as such to the construction of history, the haphazard and non-continuous event to a fact associated with others and, finally, life to existence. In the case of Stasiuk’s On the road one cannot actually get anywhere, while the narration runs a course of monotonous enumeration and boring repetition rather than following some sort of a closed, exceptional and definite route, since “the same” is more interesting than any sort of a “difference”. I regard such a travelogue to be an idiotic story. | ||

| Tomasz Szerszeń | Genex – the History of a Certain Non-place  | 163 |

Architecture as a form of repression, a non-place, a place of self-alienation and experiencing the extraordinary – this is the nature of contact with the brutalist architecture of post-communist countries. Or perhaps with its remnants: such buildings as the Genex in Belgrade are becoming a metaphor of the end of History, a reverse of the processes of modernity. Today, they come alive within yet another context: that of contemporary art. | ||

| Szymon Uliasz | The Lowlands of Hungarian Melancholy. Harmony and Entropy  | 167 |

This text endeavours to take a closer look at the sources of melancholy in the novel by László Krasznahorkai: The Melancholy of Resistance, by presenting historical and philosophical contexts, while the interpretation key involves categories of harmony and entropy. From a description of the main protagonists of the story and its adaptation – Béla Tarr’s film: Werckmeister’s Harmonies – there emerges a more expansive image of the condition of a person suffering from melancholy. | ||

| Czesław Robotycki | Indigenous and Metropolitan Artistic and Intellectual Milieus. The Example of “Piwnica pod Baranami” | 175 |

| Krystian Darmach | The Lisbon Pastelaria as the Third Place | 183 |

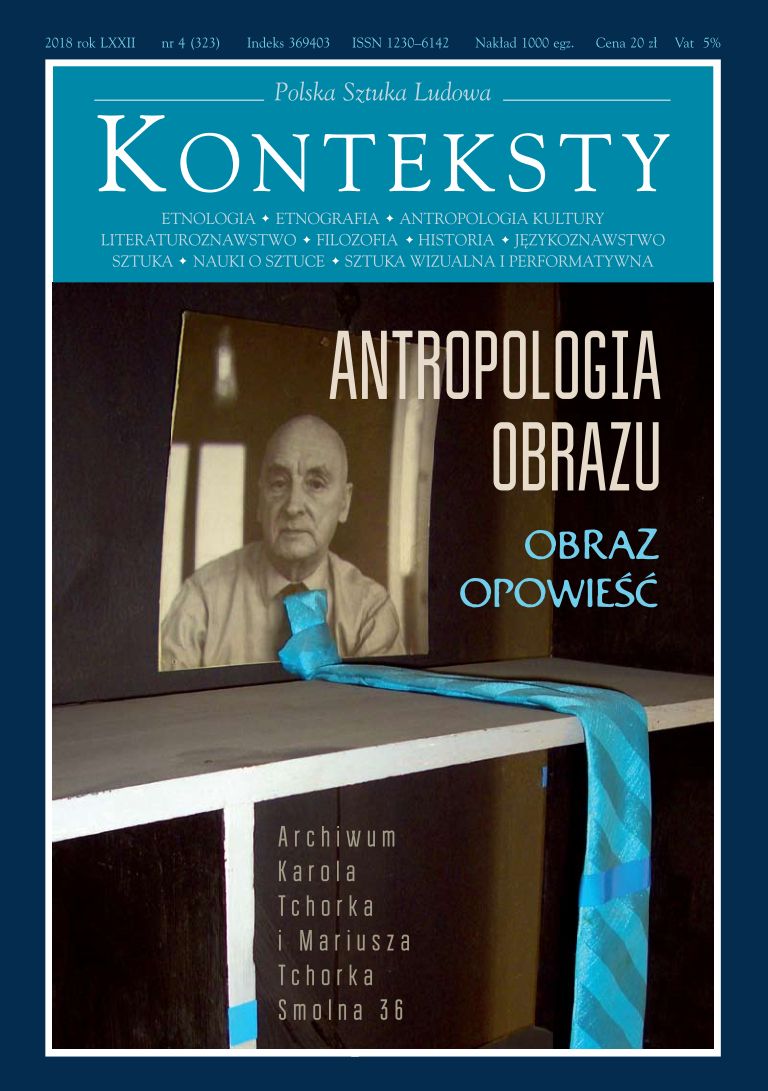

| Michalina Lubaszewska | The Photograph as the Object-relic. The Motif of the “Altar” in Literature and Cinema  | 191 |

This text is an attempt at presenting the photograph as a material object. In doing so the author portrayed the photograph as an item changing into a relic thanks to the cult with which it is surrounded by its recipients. Owing to their connotations and functions, objects-relics, even those conspicuous for their frequently hybrid states, are differentiated from the fetishes and souvenirs with which they are commonly identified. The photograph-relic, worshipped and displayed on sui generis altars, is also a literary and film motif, here subjected to detailed analysis. Despite the fact that an interpretation of selected examples of photographs-relics refers predominantly to their material dimension (showing the reification of the object of reference, as if concealed by the material qualities of the photograph subjected to cult practices) this does not mean that the psychic and transcendent sphere ceases to exist. In the case of the photograph-relic and the photograph in general material and spiritual spheres appear to be inextricable and indivisible. The described photographs-relics testify to a certain paradox: when they are worshipped and become the object of a cult, they reveal, first and foremost, their material properties through which, with redoubled force, the photographed person speaks. | ||

| Magdalena Stopa | A Little Great Story  | 197 |

A review of a book by Piotr Korduba about Poznań districts and their residents: Sołacz. Domy i ludzie and Piotr Korduba’s and Aleksandra Paradowska’s: Na starym Grunwaldzie. Domy i ich mieszkańcy. | ||

| Janina Fatyga, Barbara Fatyga, Ludwika Malarska | 201 | |

| Aleksander Jackowski | 209 | |