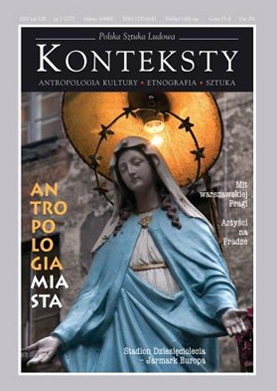

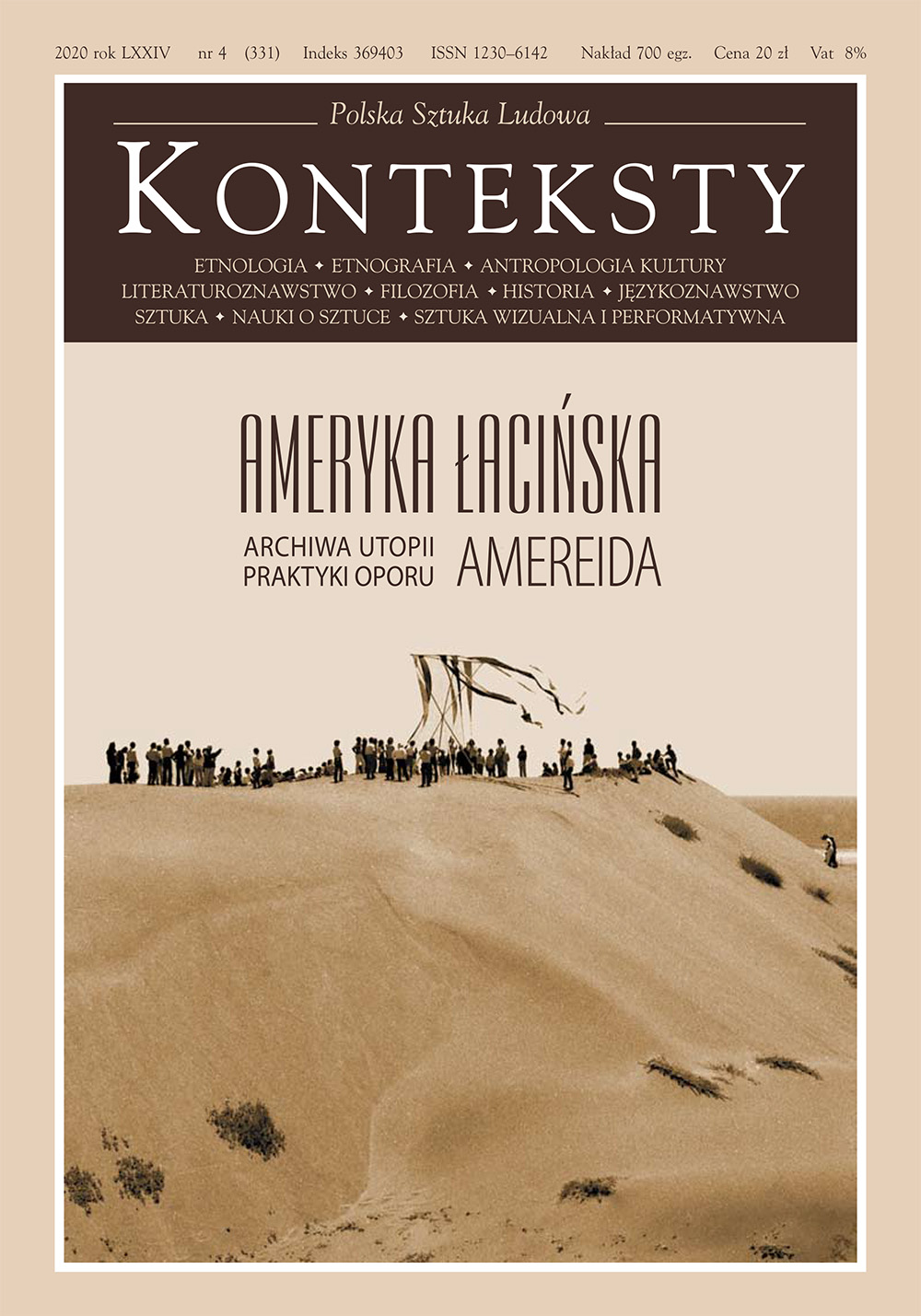

Issue 2008/3-4 (282-283) - Urban Anthropology

| *** | ||

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | 2 | |

| Desmond Harding | The Urban Imaginary and the Space of the City  | 5 |

In recent decades new theories and practices of urbanism and city planning have coalesced to form a highly visible domain of transdisciplinary discourses for studying cities as both distinct socio-cultural spaces as well as componential parts of wider networked systems, regional and global. One consequence of this development is an increasing awareness on the part of urban scholars that social processes are informed as much by symbolic and discursive practices as they are grounded in capitalist political economic practices. The Urban Imaginary and the Space of the City examines the ways in which the empirical city and its subjectively perceived image in Western culture endures as a complex and discontinuous site of convergent interests rather than a logically or conceptually clarified idea. | ||

| Ewa Rewers | From the Town Genius Loci to Town Oligopticons  | 21 |

It is becoming increasingly difficult to describe towns while using historical categories, terms or ontological metaphors such as genius loci. Secular, fragmentary, and anomic post-industrial towns subjected to communication and information do not enroot us “here”, in our places, but change us into moving images of the consumer, the tourist, the passerby, the demonstrator, and the hardworking resident, and together with the images of the streets and squares transfer us “elsewhere”. Despite the fact that today it is rather the product of marketing strategies than a live metaphor, genius loci continues to inspire researchers. What can be done so that its sense-creating force would not vanish while imprisoned in an historical costume? A proposal formulated in this text leads to a confrontation of the town genius loci with another metaphor – the oligopticon – with whose assistance B. Latour described Paris at the end of the twentieth century. Between genius loci and oligopticon there exists a bond based on a common meaning: both are known as the “tireless guard”. By blending the social and technological aspects of life in the city, oligopticon, similarly to genius loci, extracts from urban space an endless number of sites (the multiple versions of Paris in Paris, Poznań in Poznań, Gdańsk in Gdańsk), which together create a certain entity; true, it remains inaccessible for the sort of perception which has not been subjugated to the media, but it does not resemble anything else, and is mysterious and undefined. | ||

| Krzysztof Rutkowski | Wandering Writing. Paris as a Book of Signs  | 31 |

Le Livre des passages is strange work and must be read in an equally unusual manner: this is a book which opens itself on a page of its own choice and compels the eye of the reader-flâneur to delve into a certain fragment, particle or voice. A Book of Passages written by a tramp calls for a reader who is a vagabond, a brigand, and an assailant. For Benjamin, just as for Balzac, Nerval and Baudelaire, Paris was a book of signs endowed with an inexhaustible narration potential, resembling a generator of the senses, working incessantly and at top speed. The task of the poet-flâneur consists, therefore, of indicating the multi-voice, ungrasped and ungraspable richness of simultaneously transpiring narrations. | ||

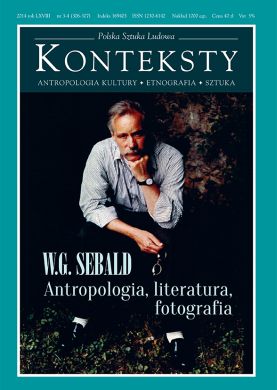

| Tomasz Szerszeń | The Towns of Walter Benjamin  | 40 |

Throughout his whole life Walter Benjamin created mini-portraits of towns, synthetic “images of thought”, sometimes no larger than the text on a postcard. They mark the places in which the life of the author of Le Livre des passages merges, as closely as possible, with writing and the text. This is the place where that which is theoretical and that which is experienced are already inseparable and undistinguishable. Benjamin’s images of cities are never a journalistic “capturing of life”: following the example of the poet Stefan George, he introduced the concept of denkbilder, which contains tension between the past and the present, between recollection and experience. Benjamin believed in the cabalistic power of the word. Just as Proust treated names, so he conceived the names of towns as symbols: Berlin, Jerusalem, Marseilles, Moscow, Naples, New York, Paris, Riga, San Indignant... | ||

| Gabriela Świtek | The Transcriptions of the Gesamtkunstwerk  | 47 |

The article addresses the question of the Gesamtkunstwerk as a key-word with which to describe the ideal of modern culture. The programme of a Gesamtkunstwerk was first explicitly formulated in the mid-nineteenth century by Richard Wagner in his essays Art and Revolution and The Artwork of the Future written in exile in Zurich after the failure of the German revolution in 1849. Traditionally seen as the invention of the nineteenth-century, the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, has been applied to a great variety of phenomena, ranging from the theatre, music, architecture, urban projects and political systems. Despite the elusive nature of the concept, some attempts have been made to set forth its essential characteristics; Harald Szeemann’s exhibition Der Hang zum Gesamtkunswerk. Europäische Utopien seit 1800 (Zurich, 1983) is a case in point. As Odo Marquard notes, the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk is already implied in Schelling’s philosophy of art and its identity system: the system (das Gesamte) becomes an artwork and the artwork becomes a system. Although the early German Romantics did not use the term itself, Friedrich Schlegel’s famous Athenaeum Fragment 116 is also considered as an anticipation of the nineteenth-century concept of Gesamtkunstwerk. The Romantic claim for the synthesis of the arts and poeticization of life opened a path for a modern utopia, where art has been endowed with a ‘redemptive’ power, and had far-reaching consequences for the development of modern aesthetics. Although the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk now seems archaic or ‘suspicious’ – especially in the context of postmodernism and its valuation of the fragmentary – it has reappeared in the expanded field of contemporary art and architecture, especially in happenings, installations and projects in public spaces | ||

| Ryszard Engelking | Insanity in a Strange Town  | 54 |

The author discusses the origin and history of the publication of Nerval’s Pandora and accentuates the differences between the narrator traversing the city (flâneur) and the insane narrator in Pandora. | ||

| Gérard De Nerval | 56 | |

| Piotr Jakub Fereński | The Curiosities of Vienna  | 60 |

In his Eine Reise in das Innere von Wien, Gerhard Roth accepted a historical perspective and combined two types of reflectiveness. By focusing on symbols, values and ideas, he filled his essays with a concentrated mixture of data, dates, figures and statistics. At the same time, he proposed a rather untypical journey to the innermost recesses of the Austrian capital. In its course, Roth reaches out for that which is concealed (in the subconscious) and thus creates a “different” portrait of the city as a silent (although by no means mute) witness of tumultuous history. The past and the present assume the form of quarters, streets, squares and assorted buildings that house institutions, brimming with law and violence, war and festivities, amusement and malady. At the same time, Roth does not shy from maligning the history of the state, the authorities, the Church, etc. An in-depth reflection on history and culture is accompanied by demystification tendencies not devoid of political demonstration. | ||

| Joanna Kulas | Mysterious Polish Towns  | 65 |

The presented essay contains a historical-literary outline of Polish adaptations of Les mystères de Paris by Eugène Sue during the second half of the nineteenth century. The author analysed Tajemnice Warszawy (The Mysteries of Warsaw, 1908) by A. W. Koszutski, Tajemnice Krakowa (The Mysteries of Cracow, 1870) by Michał Bałucki, Tajemnice Nalewek (The Mysteries of Nalewki, 1889) by Henryk Nagiel and Tajemnice Warszawy (The Mysteries of Warsaw, 1887) by Bojomir Bończa within the context of the development of popular literature. The article indicates the fundamental elements of the genre: the fairy-tale structure with a morally satisfying end, the one-dimensional protagonists, the didactic commentaries and frequent passages addressed to the reader, the motif of love and money as the prime motor forces of the plot, the expanded dialogues and, first and foremost, the specific feature of mystery in the depiction of the city, the protagonist and their past. By resorting to the instruments used by the sociology of literature, the author proposes a critique of the assessment of the Polish mystery novel undertaken by Józef Abhors, and sketches the mechanism of the functioning of this genre of popular literature. In doing so, she shows the method of involving the reader into the course of the narration by means of a created illusion of reality, and thus discloses its persuasive strategy. | ||

| Barbara Bossak-Herbst | Gdańsk in Novels by Paweł Huelle and Stefan Chwin – an Attempted Reconstruction  | 71 |

The presented article is an attempt at reconstructing models of the identity of places present in biographical novels and stories by two celebrated authors and leaders of public opinion. The author seeks an answer to the question: which parts of the Tri-City are subjected to the most intense symbolisation in the oeuvre of the two men of letters? Do their works contain recurring combinations of values associated with concrete places in the space of Gdańsk? How is the identity of people perceived within the context of the cultural identity of the place? Paweł Huelle creates a selective and vivid portrait of Gdańsk, which appears to be one of his oeuvre’s “chief protagonists”. Even more extensive descriptions of cities and the author’s experiences are to be found in novels by Stefan Chwin, who pays great attention to his closest surrounding. Both authors symbolically designate Gdańsk by pursuing an archaeology of its residents’ social memory and the micro-politics of local identity, enjoyed by numerous recipients. | ||

| Agnieszka Sabor | Jerusalem: a Question of Life and Death | 81 |

| Anna Pochłódka | “It All Started in This Town”. Papal Symbols in the Visual Surrounding of Wadowice  | 86 |

The article describes the visual surrounding of the hometown of John Paul II from the vantage point of the pope’s person, and including commemorative plaques, monuments, and information. With this purpose in mind the author applied the concept of the iconosphere, with photographs as an essential element of the article. Signs referring to papal qualities may be arranged in circles of the dissemination of the sacrum, whose centre is the parish church of the Presentation of the Holy Virgin Mary in the town market square. The first circle is thus the square itself, with the municipal office building featuring an inscription: “The Wadowice self-government ever faithful to John Paul II”. The market square also includes a Museum – the Family Home of John Paul II and a Municipal Museum, which at the time of the research displayed an exposition on the pope. A separate part of the space is composed of shops offering devotionalia dominated by likenesses of the pope. The second circle is the town. Within this range the papal narration is organised by the Karol Wojtyła Route composed of sites important in the life of the future pope and accompanied by numerous uncoordinated references. The third circle is the John Paul II Rail Trail, linking Wadowice and Cracow by means of a special “papal” train. The fourth and fifth circles of the dissemination of the sacrum encompass Poland and the whole world. Apparently, symbols of papacy constitute the myth of Wadowice conceived as a papal town. | ||

| Zofia Król | Literature and Bananas. The Reality of a City in The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa  | 101 |

The titular “disquiet” is the outcome of an opposition to outside reality, unattainable and highly desirable. Life – symbolised by unpurchased bananas – follows its course outside the windows, in the streets of Lisbon. The civil servant trapped in an office is much too mired in self-reflections and absorbed in revelling in his misery to be able to overcome disquiet and experience the presence of the world... | ||

| Magdalena Barbaruk | Buenos Aires. Fantasy vs. Metaphysics  | 104 |

A presentation of the assorted dimensions of the fantastic qualities of Buenos Aires: firstly, this is an invented city whose ontical locus is the word (assuming that the town had been created by the toponym “Bu-enos Aires” the text analyses etymologies, transcription variants, and attempts at changing the name); secondly, the town is architecturally monotonous (the city’s Hippodameian plan and symbolic centre, the Recoleta cemetery), and thus has produced the best fantasy literature; thirdly, Buenos is the realisation of a fantastic Enlightenment project by D. F. Sarmiento. The author depicts the city as a labyrinth, indicating two contexts of deciphering it: town planning (the town envisaged as a gigantic chessboard, a labyrinth of graves) and symbolic (a labyrinth of letters), showing that we are dealing with an ironic (postmodern?) variant which holds little promise of arriving at the sacral centre. | ||

| Patrycja Cembrzyńska | In Search of a Celestial Haven – a Cosmic Odyssey  | 115 |

The dialogue Timaeus by Plato remarks that we should direct our thoughts towards the realm of the eternal stars, and that our spirit is not at home here, on Earth. Its true homeland is the heavens: “[…] we are a plant not of an earthly but of a heavenly growth”. Is it possible to live differently than on Earth? Fantasies of celestial cities were pursued by Jonathan Swift, Georgiy Krutikov, and Wenzel Hablik. Subsequently, the era of space flights led to dreams of discovering a Promised Land in the universe. The Stanford Torus inter-stellar colony conceived by NASA inspired Jarosław Kozakiewicz, the author of Satopticon, which instead of being a New Atlantis turns out to be a penal colony. | ||

| Dariusz Czaja | Fragments of a Venetian Discourse  | 125 |

This text is part of a book (in print) on the ways of portraying Venice in imagery and word. Upon the basis of a number of selected examples (including an essay by E. Bieńkowska: Co mówią kamienie Wenecji? (What Do the Stones of Venice Say?), a sketch by G. Simmel: Venedig, a novel by J. Andruchowycz: Perwersja (Perversion) the author demonstrates various possible strategies of representing the town in linguistic discourses. By applying the semiotic concepts of a town’s Text (in order to designate a holistic corpus of individual texts about Venice), he accentuates the motifs that organise them, searches for their enrolment in narration schemes, and follows the game, conflict and tension involving contradictory likenesses of the town | ||

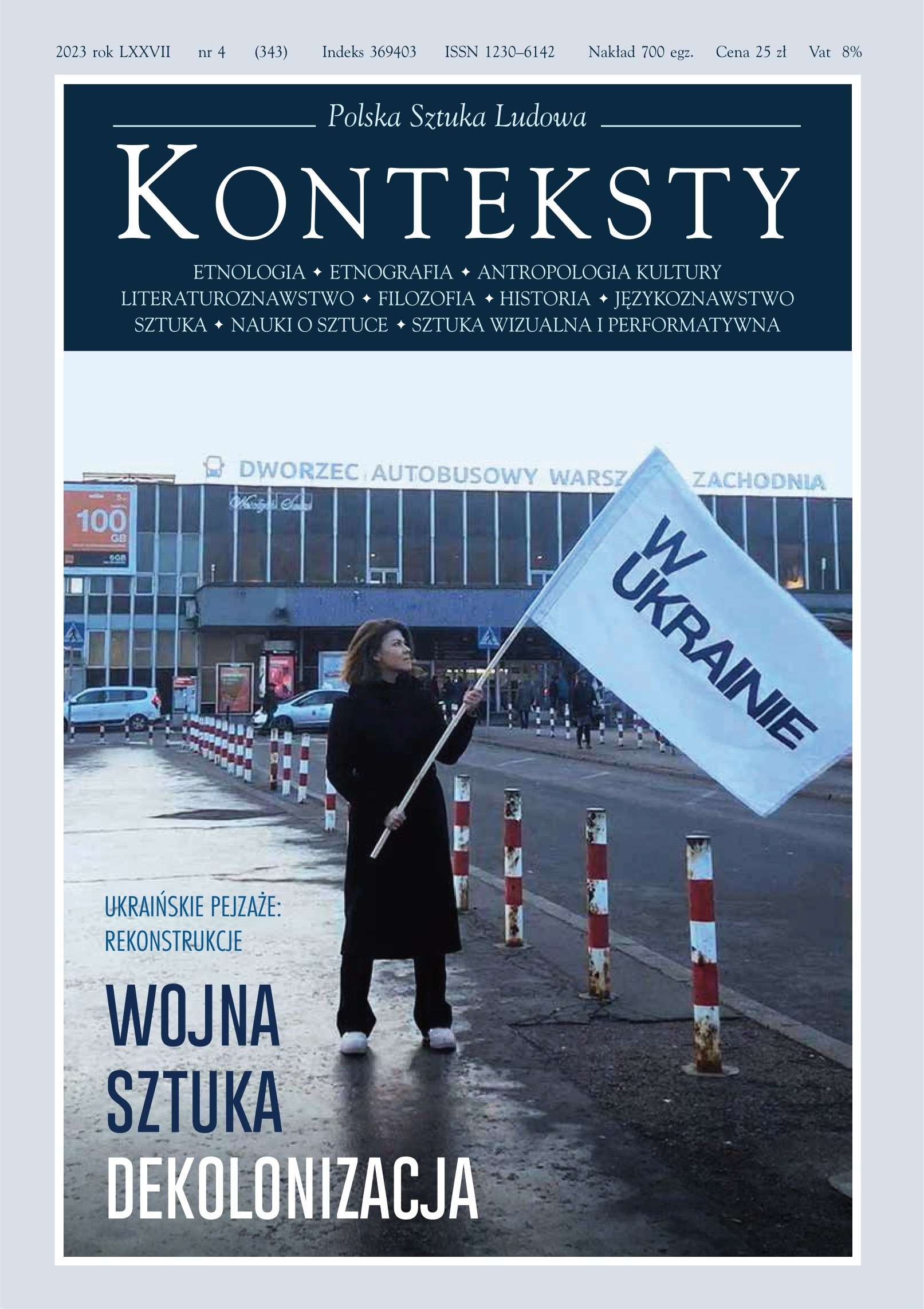

| Radosława Olewicz | A Wartime Town. A Report from Besieged Sarajevo  | 149 |

This anthropological story deals with Sarajevo, a town submerged in war, where contrary to all odds life continues to follow its course; daily events are salvaged thank to human ingenuity and “the texts of culture”. The author paid special attention to analysing the topos of the “closed town”, with its logic ofa “world turned upside down”, a characteristic suspension of “normal” time, and a special comprehension of space. In doing so, she shows the similarity between the descriptions of time and space of wartime Sarajevo and Leningrad under siege. | ||

| Jacek Sempoliński | The Provinces, Dreams. Excess  | 170 |

The author maintains that a contemporary work of art does not exist as such only in a thicket of words. Today, we are witnessing the presence of several thousand world-outlook conceptions of art, which the artist must know in order to meet the prevailing demands and become a creator for every occasion. The paradox of this situation consists of the fact that someone who is to be the most creative component of this process ceases to be such because the only creative people are those who talk about it while objectifying the artist. An excess of words and artistic undertakings is a feature characteristic for contemporary culture. | ||

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | “The Archaic Landscape”. On the Provinces, the Experiencing of the Town, Warsaw and the Photographs by Leonard Sempoliński – a conversation with Jacek Sempoliński  | 174 |

A conversation with an outstanding artist and painter about anthropology, painting, pre-war Warsaw, the Praga district and photographs by the artist’s father, Leonard Sempoliński. | ||

| Aleksandra Melbechowska-Luty | Jacek Sempoliński  | 189 |

The author outlines the artistic biography and geography of the titular artist, whose life followed two courses – between the large city and rural existence. The artist became acquainted with the towns of Italy, France, Spain and The Netherlands, while simultaneously immersing himself in the life of the Polish province, where he worked. Sempoliński experienced the landscape as a sign of an energy that creates being and as ontological knowledge about the construction of space and matter. | ||

| Hubert Kowalski | The Sculpted Decoration of the Kazimierzowski Palace  | 193 |

The history of the titular edifice goes back to the first half of the seventeenth century when its construction was initiated by Zygmunt III Vasa. Originally, the building fulfilled the function of a suburban villa, regarded as a supplement of the official royal residence at the Royal Castle. The palace was erected in the Baroque style, but successive redesigning changed its appearance to Late Baroque and Classicistic. Totally damaged by fire in 1944, the palace was reconstructed after the second world war. The large number of the transformations of the palace solid makes it impossible to recreate the sculpted decorations, but basing himself on archival information, iconographic material, and preserved elements of the embellishment the author brings the reader closer to this interesting iconographic programme. | ||

| Hanna Faryna-Paszkiewicz | The Praga Landscape  | 203 |

The uniqueness and character of the Praga district in Warsaw are determined by a number of features, unchanged for centuries. Owing to its location the district remained in an unsymmetrical configuration vis à vis the City on the left bank of the Vistula, and in an outright opposition expressed in the social composition of the residents, the origin of the population (a large percentage of Russians and Jews), an increased crime rate, and specificity consisting of an intentional, frequently cultivated and stressed distinction compared to other parts of the capital. This phenomenon remains discernible up to this day: Praga, together with the fast disappearing but still existing Różycki Bazaar, the domes of the Russian Orthodox church of St. Mary Magdalene, or the ludic atmosphere around the Zoo, is a separate world. The social climate and brogue of the local residents appear to hold their own, challenged by the process of transforming, right in front of our eyes, old factories into a cultural Mecca of the capital, thus offering the district a chance for promotion, which will either overwhelm it or became the reason why Praga will lose its natural ambiance without gaining a new image in its stead. | ||

| Paweł Elsztein | The Warsaw Praga Known and Unknown  | 212 |

The sketch deals with the Warsaw district of Praga, the author’s birthplace. In a presentation of less known historical facts from the turn of the nineteenth century P. Elsztein tries to evoke the daily ambiance of a noisy and busy part of town, always in a hurry. In doing so, he cites numerous descriptions by assorted publicists, poets and writers – the chroniclers of Warsaw and especially Praga. | ||

| Iwona A. Oliwińska | Genius Loci and the Spatial Behaviour and Lifestyle of the Residents of Szmulki  | 237 |

The district of Praga and Szmulowizna had been treated for four centuries as a distinctive and inferior part of town. Nonetheless, this fragment of Warsaw possesses its own genius loci. It served as a haven for people not welcome on the left bank of the Vistula (such as runaway servants, thieves, bigamists, the poor and the homeless, petty artisans and shopkeepers, and the Jews). It was also chosen by representatives of the gentry, who treated the quarter as a sui generis hinterland, and used their residences only when they came to meet the king. Today, Praga is the destination not only by people evicted from the other bank of the Vistula, but the place of residence of artists and young university graduates. In the past, it was also chosen for industrial enterprises not fit for the elegant capital (charnel houses, tanneries, joiners’ and dye shops, wire works, steel mills, etc.). For centuries, Praga was the site of flourishing trade and crafts. It was, and still is, full of street bazaars, open-air stalls, assorted small shops and workshops, where one could purchase or repair everything. Here, time seems to run a less hurried course, almost resembling that of a small provincial town. This particular section of Praga North also features a different architecture, whose development and form were influenced by the owners of Praga and Szmulowizna and the partitioning and local authorities. For hundreds of years, attention had not been paid to the well-balanced progress and development of Praga and Szmulowizna, regarded as an unattractive part of Warsaw of little interest to investors. Not until the 1990s was the appeal of the district, with its pre-war houses and a so-called ambiance, actually noticed. This was the period of the revitalisation of the old and neglected town houses (although only in select quarters). The history, folklore and brogue of Praga were promoted. The authorities of the district created opportunities for the newly settled artists, transforming industrial space into its cultural counterpart, and approving cooperation with local social partners. | ||

| Janusz Sujecki | 78 Targowa Street. The History of a Photographer’s Studio  | 250 |

A brief introduction to the history of a photographer’s studio, once working in 78 Targowa Street. | ||

| Anna Kuczyńska | Urban Anthropology – an Area of the Concentration of Anthropological Problems  | 253 |

A proposal of a synthetic presentation of an urban anthropology project, which could constitute a conceptual framework for assorted empirical urban studies sufficiently extensive to encompass an anthropological interpretation of the “world of the life” of a man of letters. The reflections are preceded by an outline of assorted stages in the moulding of the concept of urban anthropology, both in Poland and in Western science, which the author treats as a “self-reflection” motif in urban anthropology (starting with the conception of “expanding the object of ethnography” up to a change in the paradigm of anthropology). In a further part of her text the author seeks structures “merging” numerous and divergent urban themes. The fundamental category of being – place, and in the dimension of the humanities – space and place, is a point of departure for anthropological motifs: the multiplicity of the senses and meanings of places in the town in their social, philosophical (the experiencing of “being in space”) and artistic dimension. The second keystone is time. The statement, recurring in “town planning” literature in the manner of an axiom, namely, that the town is a permanent and complex temporal structure, creates a framework for an interpretation of a considerable part of urban experiences, collective conceptions and social practices: individual and collective memory, commemoration and annulment, revitalisation, nostalgia, etc. The temporal dimension discloses the connection between the town and culture, expressed in an ideological and literary discourse. Yet another fundamental concept of anthropology, i. e. the identity due to people and places, also refers to the past. | ||

| Magdalena Kroh | 63 Targowa Street  | 268 |

The author, who lived in Targowa Street (the district of Praga) for 15 years, from 1948 to 1963, presents the reality of the district from that period as seen by a child and a girl. A confrontation of feelings originating in an intelligentsia home and the reality encountered on a daily basis in her closest surrounding. | ||

| Anna Kuczyńska | “Places and Neighbourhoods”. Studies 2004-2006  | 283 |

A brief introduction to the problems and range of the titular research project, realised as part of an ethnographic laboratory conducted in the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at Warsaw University in 2004-2006. The studies, concentrated on places with a diverse identity, were carried out in Warsaw and its environs. They include research by Agata Chełstowska, Katarzyna Gmachowska, Katarzyna Kuzko and Magdalena Majchrzak. | ||

| Katarzyna Gmachowska | “Glass Houses”. The Żoliborz Warsaw Housing Cooperative. A Place Embroiled in History  | 286 |

The author delves into the identity of a place in urban space exemplified by the Warsaw Housing Cooperative (WSM) in the district of Żoliborz – a model of the town planning tendencies of modernism, emerging from the retrospective accounts by its residents. The context for an attempt at evoking the subjective experiencing of this particular place is the discourse held until this day and concerning the foundations of such ideological projects as the WSM and their consistent realisation. | ||

| *** | ||

| Ludwik Stomma | The Anthropology of History. Sport  | 295 |

The author outlines the history of the Olympic Games, which he compares to war hostilities. While proposing the organisation of cyclical international sport competitions, Baron Pierre de Coubertin referred to the tradition of the Greek games. L. Stomma considers sport not as a venture involving cooperation or a great humanitarian idea, but as an invaluable safety valve to alleviate confrontations and nationalism by relegating them to the sidelines and onto a relatively controlled course. Just as the rivalry of creeds inevitably resulted in religious wars, so strife on the playing fields, in one form or another, becomes transferred to the stands. | ||

| Antoni Kroh | The Old River Valley. Money, Thriftiness, Ingenuity  | 301 |

Continuing his series of reminiscence entitled The Old River Valley published in “Konteksty”, the author based himself on post-war home economics and focused his attention on the attitude of the intelligentsia towards money and ownership as well as its economic life and sources of livelihood. | ||

| Antoni Kroh | The Old River Valley. The Security Bond  | 312 |

A successive fragment of The Old River Valley, describing the amusing history of a security issued by the Domestic Economy Bank and bequeathed to the author by his aunt. | ||

| Jan Gondowicz | Wasp  | 314 |

The significance of the works by the French entomologist J. H. Fabre for the formation of the world outlook of S. I. Witkiewicz – Witkacy had been noticed quite some time ago. This particular study accentuates the characteristic role played in the latter’s imagination by one of the insects described by Fabre – the digger wasp sphex, due to the fact that H. Bergson recognised its behaviour as a key example of instinctive knowledge. Against the background of a psychomachy with the detested Bergson, Witkacy developed a mythology of the wasp, whose message is close to that of the mythology of the praying mantis in the essay by R. Caillois. | ||

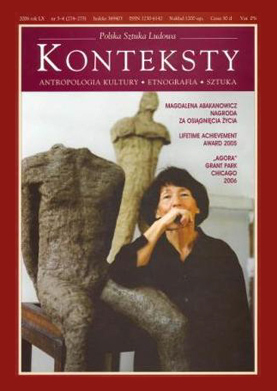

| Aleksander Jackowski | Stanisław Zagajewski  | 321 |

Reminiscences about Stanisław Zagajewski, whose oeuvre was a negation of folk art, difficult to grasp or classify. Zagajewski’s works were associated with his personality and visions; self-generated, they were close to the concept of Art Brut. Without succumbing to the impact of culture they remained independent of styles and models. Zagajewski was a compulsive sculptor and art constituted the sense of his life. He was featured at numerous exhibitions and became the topic of several films, albums and numerous texts in assorted books. | ||

| Stanisław Barański | 324 | |