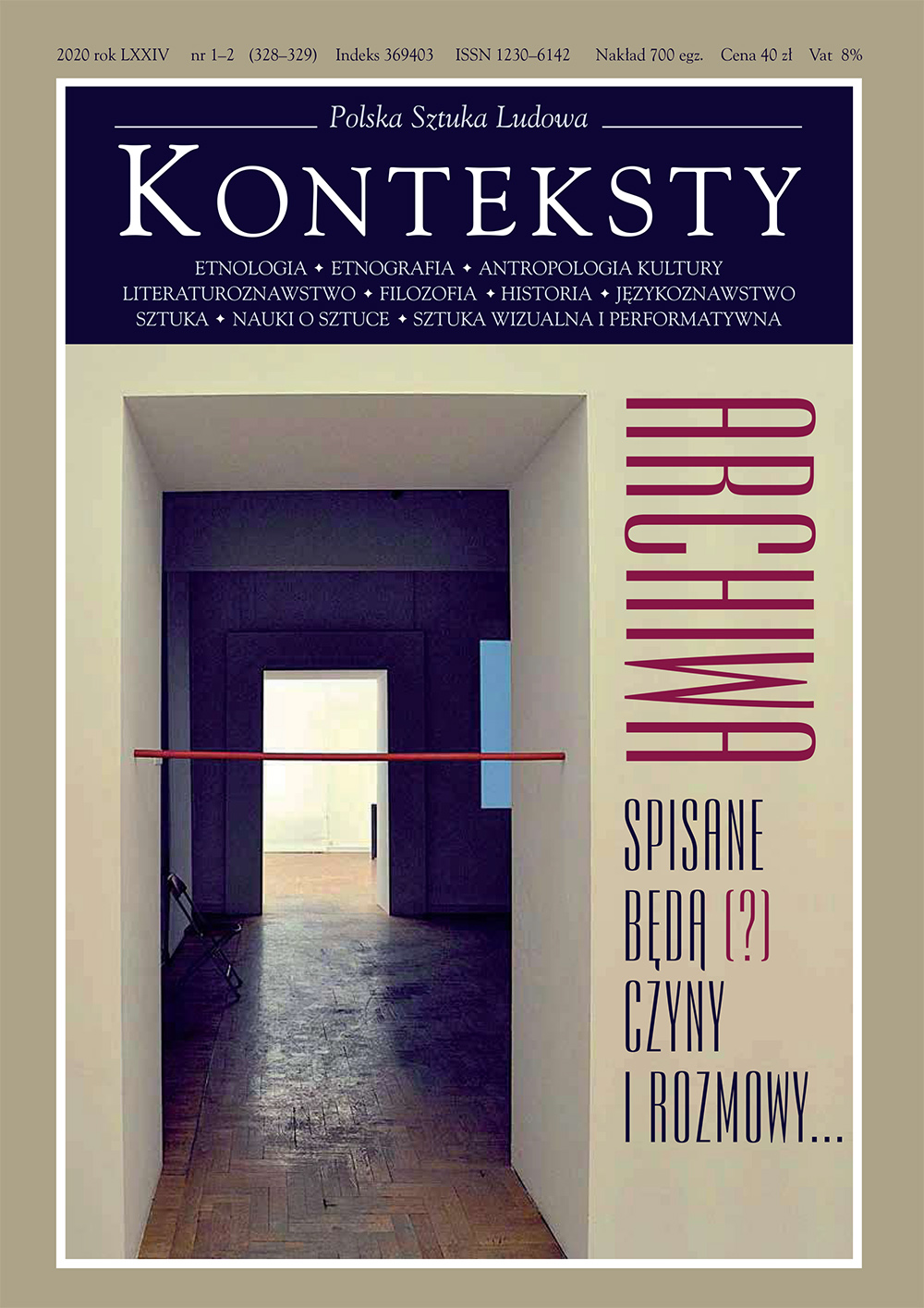

Issue 2004/1-2 (264-265) - Konteksty

| Zbigniew Benedyktowicz | 3 | |

| * | 6 | |

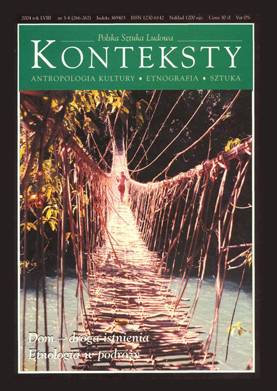

| * | The Home — a Way of Being. Interdiscyplinary Multimedial Exhibition Project | 7 |

| Julia Hartwig | 12 | |

| Szymon Wróbel | Home, Homelessness, Domestication  | 13 |

Man is deprived of the possibility of making himself at home anywhere in the cosmos without having earlier experienced homelessness. The author defends the thesis about the three ontogenetic stages which co-create the biography of our life - the home (childhood), homelessness (growing up), and domestication (adulthood), present also in the great novels which co-constitute the canon of Western literature. Within the political context the ideology of domestication is neo-conservative, the ideology of homelessness is postmodernistic, and the ideology of domestication is modernistic. Moreover, conservative nostalgia for the home and the promise of apocatastasis are false, since the home (the sort dreamed about by the conservatives) has never existed. We are doomed to an endless effort of transforming the savage nomad quality of life, discovered in the postmodern world, into domesticated fragments of reality. There is a chance of finding the home only somewhere on the very edges of reality, far away from home. | ||

| Zbigniew Mikołejko | The House of God and His People  | 20 |

An attempted recreation of a play of meanings involving the concept of the “house” (bet) in the first seven book of the Bible - the Pentateuch, the Book of Joshua and the Book of Judges. The present-day arrangement of the Holy Scripture suggests that a radical sacralisation of the house had taken place already in the mythical beginnings of the history of Israel, at the time of Abraham and his successors. Meanwhile, an interpretation of the first Biblical books in their actual chronological order based on the dates of origin, proves something quite different: true, in the oldest, the Book of Judges, the house is special and sanctified, but its sacralisation is discreet and almost imperceptible. It assumed an extreme form in the later myth of the “exodus” from Egypt, which was constructed upon the basis of a fundamental anti-thesis of the house-cosmos and the world (chaos, darkness and evil), the “house of Israel” and the “house of bondage”. Subsequently, the myth became a paradigm, and the dualism created in its interior, symbolically reinforced with the blood of the paschal lamb, was subjected to absolutisation. As a result, the people of Israel can be interpreted as the “house of the Lord”, and both its particular offshoots (tribe, clan and, in particular, the family) as well as the very manner of conceiving the house (from its material bases to the religious dimension, even in those instances when a house is associated with the forbidden syncretic, Yahveh-idolatrous culture) will be sanctified. | ||

| Adam Bieszk | 31 | |

| Beata Spieralska | A Roof over the Head. The Concept of the “Home” in Indo-European Languages  | 33 |

This article is, first and foremost, a voice in a discussion on the ambiguity of the proto-Indo-European root *d e/omh2. The presented thesis, illustrated by means of numerous parallells from assorted Indo-European languages, proposes that two basic meanings confirmed for *d e/omh2, namely, “home as a unit of social division” and “home as a construction”, be recognised as occurring next to each other already during the proto-Indo-European epoch, and as closely connected. The social application of the concept of the “home” implies its material use. The distinction of a social group calls for territorial distinction. The feeling of security linked with “being at home” can come into being only thanks to the differentiation and construction of an inner space opposed by the outer world, full of unidentified threats. | ||

| Jan Gondowicz | The Shelter  | 37 |

The Shelter (Der Bau, 1923), an example of Kafka's late prose, is a disturbing description of the mental situation in which a fantastic subterranean animal harbouring the ambition of creating the perfect shelter, has found itself. As it recognises the futility of this endeavour the hapless creature succumbs to a paradox, inseparable from attempts at isolating itself from the world. This paradox of the boundary has two interpretations, paranoiac and existential, which suggest that full security can be discovered only on the other side of existence. The paradox in question, Kafka proposed, comprises an aporia contaminating all reflection about identity. | ||

| Anna Eleonora Kubiak | Nostalgia and Confluent Communities  | 40 |

The article brings the reader closer to the concept of “nostalgia” envisaged as a narrative cultural practice. Nostalgic narration is described by resorting to references to the category of memory, time, experience, and mythisation. The author analysed nostalgia as cultural praxis within a perspective described by James Clifford as “troubles with culture”. This practice has become a remedy of sorts for creating artificial distances which restored the distinctions, oppositions and species lost in contemporary culture. A representative example is the problem with the interpretation of popular culture whose critics are embroiled in a nostalgic paradigm of culture. A further part of the text presents an abbreviated historical intepretation of nostalgia as a melancholic state of the spirit. Finally, the author proposed the concept of “confluent communities” for the purpose of characterising contemporary social groups possessing the features of “communitas” (according to Victor Turner), but sustaining the individualism of the participants. | ||

| Antoni Kroh | The Old River Valley III. The Infinity of Bitter Reflections. A Metal Cash Box. The Female Body. A Seal Ring and a Ring  | 44 |

More miniature stories based on the author's recollections about people, objects, fascinating cases and events. | ||

| Cyprian Norwid | 53 | |

| Aleksandra Melbechowska-Luty | To Lean My Head against Convent Walls". A Chronicle of the Homlessness of Cyprian Norwid  | 54 |

Cyprian Norwid never enjoyed a real, tranquil and happy home. Born in 1821, he spent only the four first years of his life in the family manor house in the village of Laskowo-Głuchy (Mazovia). Orphaned by his mother, he was brought up by relatives and guardians, and spent some time in boarding schools. An emigre since 1842, Norwid travelled a lot, frequently changing his places of residence, ateliers, hotels and boarding houses. Consequently, he envisaged the home as a mythical place, a permanent “point” in the world, much desired and never attained. This is the reason why his poetry and art bear the imprint of homelessness, expulsion outside the bounds of normal existence, and the experiencing of the ruins of life and home (but also of temples, cemeteries and ancient buildings) . The endlessly accompanying “voice of the ruins” became one of the key concepts in Norwid's reflections launched within the range of the philosophy of history and metaphysical experiences as well as in ontological and transcendental categories, and as a projection of his own experiences and the myth of the “poete maudit”. In 1840 Norwid lived in Italy, where he toured numerous cities; he also went on a sea voyage to Greece and travelled across Silesia, Greater Poland and Germany. In 1846 he was arrested under political charges and incarcerated in the Hausvogtei prison in Berlin, were he spent several weeks “on damp straw” and then in the prison clinic. Later, he moved to Rome; in 1848 his studio was described by Zygmunt Krasiński in a magnificent “portrait in an interior” of the young poet and painter. At the beginning of 1849 Norwid left for Paris; since from the very outset his stay in France was marred by a rising tide of misfortune, poverty and conflicts with those surrounding him, in December 1852 he sailed for New York, where he worked as a draftsman for the 1853/1854 World Exhibition Almanac. Two years later he returned to Paris (via London), “broken for the rest of my life”. His literary and artistic oeuvre, with its characteristic innovativeness and profound reflections as well as its moral and philosophical message, was regarded by Norwid's contemporaries as hermetic, eccentric and pretentious, and thus worthy of ruthless criticism as, i. a. the product of “crippled genius, frenzy and folly”. The author of Promethidion was ridiculed and disproved, and found it difficult to sell his paintings, drawings, water colours and illustrations, and to publish his literary works. Throughout his whole life he obsessively returned to recollections of his childhood years, painted houses, women and children, and just as obsessively contemplated the theme of the abandoned, the rejected and the unjustly condemned, whom he depicted in his writings and sketches. The years 1875-1876 brought a loss of all hope and a deterioration of Norwid's health - he suffered from tuberculosis. At the beginning of 1877 his wealthy cousin, Michał Kleczkowski, forced him to concede to move to a hospice - the St. Casimir Home, managed by nuns in Ivry, on the outskirts of Paris. The poet, who arrived there on 9 February of the same year, found his isolation from the world and people closest to him a painful ordeal, and suffered from that “syndrome of enclosure” which pervades all substitute homes intended for the unwanted, the sick or the disabled, places governed by a system of rules comparable to prisons, hospitals or sanatoria. He became fully aware of the fact that “Hell is the others”, feared the lowly inmates — old veterans prone to clashes and quarrels, and requested to be permitted to take his meals after everyone else had finished eating. Despite numerous obstacles, he continued to write and paint (i.a. his fellow inmates and self-portraits). Norwid died on 23 May 1883 at the age of 62. A year earlier, Pantaleon Szyndler executed a large portrait showing the author of Vade-mecum as the “ideal” inspired poet, artist, thinker and prophet. The funeral was held at a small cemetery in Ivry; after the concession expired, Norwid's ashes were twice transferred to graves in Montmorency. In 2001, which marked the 189th anniversary of Norwid's death celebrated in Poland , an urn containing soil from his third, mass grave, was placed on Wawel Hill. | ||

| Monika Rudaś-Grodzka | Europe and the Bull  | 67 |

The dominating motif in Polish national literature, intent on inciting pro-independence strivings, was the ideal of sacrifice and devotion. For centuries, the patriotic matrix rendered indelible a stereotype claiming that male sacrifice differs from its female counterpart. Courage, strength and valour accompany the man, and devotion and fidelity - the woman. The man sacrifices his virtues, while the woman is usually sacrificed. This relation is illustrated, from the female vantage point, by the myth about Europe, which additinally indicates fundamental features distinguishing European culture: on the one hand, the power of sexual activity (rape) and, on the other hand, unblemished innocence (submission); the beast and the virgin yield dynamic tension. In Quo vadis, the novel by Sienkiewicz, the scene in which a bull carries Ligia evokes the stirring history of Europe. Assorted interpretations frequently drew attention to the fact that the scene symbolises the triumph of Christians over pagans. This is not the only approach: Ligia was perceived predominantly as Poland extracted from the hands of the German invader. We are dealing, therefore, with a characteristic sequence: Europe, Ligia, Poland - the links in a national chain. In the case of Sienkiewicz's novel abduction and rape denote in the mythical sphere the sacrifice of a woman performed in order to secure the Polish nation victory in the battle against its enemies. The death of an innocent woman-Poland is the redemption of all the evil in the world. Such distinct female characters include Danuśka, the heroine of Krzyżacy. Abducted and tortured by the Teutonic Knights, she loses her mind. In pain and deranged, she ultimately dies, while the untold story of her rape remains part of the backdrop. The Christian-patriotic myth concealing the traumatic experience is placed in the foreground, thus condemning her true plight to oblivion. Once we ,,remove" the upper stratum of the myth, well imprinted in our treasury of national symbols and indicating the highly valued rank of a woman's sacrifice, we may see the heretofore concealed meaning, and decipher the myth as a tale about rape and the deprivation of its victim of the right to tell her story. | ||

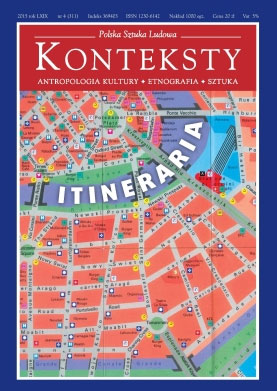

| Peter Martyn | Warsaw - a Digest  | 72 |

A review of David Crowley's Warsaw, published by Reaktion, London 2003, in a series of books dealing with the rapidly changing townscape of such metropolies as Berlin, Paris, London and Tokyo. | ||

| Kornelia Binicewicz | Green Room  | 77 |

An essay on the recurring recollections and dreams about the childhood home. In her reconstruction of an image of the home, the author cites numerous sources and literary representations as well as theatrical spectacles by Tadeusz Kantor. | ||

| Julia Hartwig | 85 | |

| Tomasz Szerszeń | The Town and Photography  | 87 |

The article is composed of four mini-essays showing multiple connections between photography and the modern city. The essays situate the symbolic beginnings of photography in the great transformation of towns which occurred during the nineteenth century, and derive modern familiarity with the town from an awareness of the loss of a holistic contemplation of the world. The Town and Photography also considers nostalgia in photography, the nostalgic “penetration of the town”, the joint experiences of the flaneur and the photographer, the “metaphysical” structure of Paris from the turn of the nineteenth century, the practice of collecting towns. All this remains within the context of Rilke's poem which claims that the “real” world is being destroyed, leaving behind its mere likeness. | ||

| Ewa Malec | Genius loci in Wrocław  | 93 |

An attempt at capturing a fascinating and unique phenomenon in the history and culture of postwar Poland - the transference of Lwów, lost due to the Yalta pact, into the post-German fibre of Wrocław (Breslau), obtained as a result of the same pact. The author analyses the phenomenon of the residents of Lwów living after World War II in Wrocław. The idealised lost Town, which existed already only in their imagination, combined with an entirely alien city whose indigenous inhabitants were also expelled, created a new and incomparable quality in postwar Poland. | ||

| Ewa Domańska | Necrocracy  | 102 |

A presentation of The Dominion of the Dead, a book by R. R Harrison, who was inspired by the philology of Vico and the ontology of Heidegger. Consequently, he wrote about the specific status of the dead and the relations between the living and the deceased in Western culture, both in the past and today. E. Domańska reconstructed the theoretical basis of the book and indicated its thematic motifs, important for contemporary humanistic discussions. Such motifs situate Harrison's publication within a research orientation that contests the fashionable “regime of the new humanities”; the characteristic feature of this study is its anthropocentrism, humanism, and enrootment in the Christian world outlook. | ||

| Jadwiga Rodowicz | Vision in a Mirror  | 108 |

A shining surface of a mirror, and a vision of the image reflected in it, is an important element of the traditional Japanese culture. A spotless mirror has been compared to the pure, original human heart. In the present article the author tries to concentrate on the mirror as an object of ritual and religious reverence and trace down a few instances of the “looking into a mirror” as an important literary motif, as recorded in ancient texts. First bronze mirrors arrived in Japan at the beginning of the Yamato state, between 3rd and 6th centuries, and were used mostly as ritual objects, and insignia of power, bestowed on local leaders. Together with a sword and a coma-shaped jewel they constituted a triplet insignia of the imperial power. Bronze mirrors were placed in the tombs of the aristocracy and it was believed that they not only reflect, but also produce light and ensure a peaceful rest for the departed soul. Patterns on the reverse of mirrors are studied as a source of information on the ancient material culture of Japan, and they prove strong links to the continental Asia (Korea and further West). The most important change took place probably when the mirror was enshrined as an embodiment of the Sun-Goddess Amaterasu in the grand Ise shrine, around 5 th century. The Holy Mirror (yata-no kagami) was then established as a substitute of the Goddes herself, and had to be kept in imperial bedchamber. An image reflected in the mirror appears first in Japanese literature in a myth of marriage between princess Konohana and Hiko Hohodemi, who actually meet at a well curb and see each other's face first in a water mirror. This motif is echoed in a famous Noh play by Zeami Motokiyo, when a woman looks into a well and sees the reflected face not of herself, but of her late husband. Minors have been used by crypto-Christians (kirishitan) in Japan as objects of religious worship in 17th century. The mirror is an important element of the Noh theatre, as it is before it that the actor changes into a character. Staring into a mirror, with the mask on his face, is the last most important moment before the actor enters on the stage. Also establishment of the oldest Noh troupe, Komparu, is related to the cult of the mirror, as it was built next to the Kasuga Shrine in Nara, where the Holy Mirror was kept. The original name of the Komparu group was Enman'i-za, which can be translated as a Group of the Round Disc, or Group of the Full Circle. | ||

| Zuzanna Pędzich | The Dance in the Mourning Ritual and Its Application in Therapy  | 117 |

In her presentation of choreotherapy the author considers dance in cultures of the past, conceived as a specific mourning ritual, which fulfilled therapeutic functions and which today could prove useful in the treatment of persons who find it difficult to come to terms with their loss. Regardless whether the latter concerns the death of someone close to us, or the loss of physical prowess or health, the dance enables us to gain support within a group, and makes it possible to express sadness, despair or longing with the assistance of motion. Finally, by performing the role of an unusual purification instrument, the dance assumes the form of a true remedy. | ||

| Maciej Rożalski | Butoh  | 122 |

Butoh is a Japanese dance which came into being after the second world war, drawing inspiration from the traditional No and Buyo theatre, the concepts of prewar German Expressionism and Antonin Artaud's “theatre of cruelty”. Emerging as an expression of protest against the expansion of American culture in postwar Japan, Butoh was supposed to echo the pain suffered by the victims of the nuclear holocaust. Owing to shocking scenes stressing the biological aspect of the human body and the themes of death and disintegration which pervaded the earliest spectacles performed by the Butoh dancers, this form of art became described as “the dance of death”. Although its present-day version is much gentlier than the original, and its contents exceed protest against Western civilisation, the daring selection of motifs and intense forms of transmission have not lost their stirring qualities. | ||

| Rystyna Zwolińska | Magic against Reality. Distinct Painting  | 129 |

Jerzy Nowosielski, the widely admired distinct painter, is the author of the following statement: “I am not concerned with painting. This is not to say that I am indifferent to the nude, the landscape or still life. I am interested in the magic which we apply towards reality with the aid of painting”. Those three sentences contain the artist's abbreviated philosophy of art, and are the best possible commentary to his canvases. The presented text is an attempt at developing this succinct abbreviation and bringing it closer to the contemporary recipient. | ||

| *** | ||

| Waldemar Kuligowski | Anthropology, Love, the Study of Culture: Forgotten Bonds  | 133 |

In this introduction to material from a scientific session entitled “The Anthropology of Love” the author declares that love is a composite cultural construction delineated by a relatively constant set of rules, which additionally demonstrates regularities that make it possible to examine it. It is, therefore, necessary to analyse love in the manner of ideas, styles in art, discursive formations and political doctrines. The object of anthropological interpretations would consist of cultural and social images and “public symbols” of love; most generally speaking, the stake would be to define and study the symbolic universe of love. | ||

| Waldemar Kuligowski | What the Heart Thinks the Mouth Speaks? Fragments of Love Discourses  | 135 |

Roland Barthes wrote about the loneliness of the love discourse. In the opinion of the author, present-day love is the topic of no longer a single but of numerous discourses, although such multiplicity does not signify the elimination of loneliness as a feature. An attempted presentation of several select l’amour-passion discourses found in contemporary culture upon assorted levels. Some perceive contemporary passion as unutterable (Wittgenstein, Lacan), others see it as a simple strategy of choosing partners with the most perfect DNA chain (sociobiology), while still others maintain that the union between a man and a woman is the outcome of patriarchal tyranny (the feministic discourse). The icon of love is also used as a measure for seducing clients and multiplying capital (passion in an advertisement of a pub), while the idiom of new dramaturgy becomes a series of brutal and frequently obscene images (Sarah Kane, 4.48 Psychosis). What are we to do with such elements of this puzzle, and will love continue to be the resultant pattern? | ||

| Agata Chałupnik | Schoppenhauerian Inspirations in the Early Prose of Zofia Nałkowska  | 138 |

Alongside Baudelaire, Weininger and Freud, Arthur Schopenhauer was one of those nineteenth-century thinkers who established the identification of woman and nature within the discourse of the epoch. Nature is rendered demonic, monstrous, and threatening for man, envisaged as a pure creative spirit. Zofia Nałkowska accepted this identification of femininity and nature, but re-evaluated it. She conceived femininity as a spontaneous and creative activity, as beauty and fertility. The second Schoppenhauerian motif in Nałkowska's prose is love, which indubitably remains the most important human, and particularly female, experience. Love, even if humiliating, branding and deeply painful, is better than its absence, as evidenced in almost all the novels by the author of Granica (Boundary). More important, inspired by Schoppenhauer, Nałkowska did not accept his misogynism, and while swayed by “the greatest enemy of women” she affirmed both women and femininity. | ||

| Małgorzata Szpakowska | Sex and Power  | 142 |

The author puts into order the problem of the relations between two spheres of reality: sex and power, frequently described in literature. This proposal, which came into being in the course of the seminar: “Nature in Culture. The Anthropology of Sex and Gender”, conducted by the author, consists of distinguishing four prime levels upon which the discussed relation is situated. The political-ideological level is composed of two types of activity: propaganda and repression, the first being presented upon the example of Nazi and socialist propaganda. The second — exemplified by the Third Reich — is contained in the extreme explication outlined by Wilhelm Reich (the path towards political liberation involves extricating children from the authoritarian family, sexual liberation, and universal orgasm) and Alice Miller (persons who were physically assaulted in childhood grow up to be tyrants and criminals). Upon the second level of “gender politics” Kate Millet introduced a concept associated rather with cultural gender than with sexuality, namely, gender politics, conceived as all strategies aiming at the maintenance of a (naturally, patriarchal) system. In this case, power denotes simply the power of man, and its foundation is human sexual differentiation. The third level - the distributed power of the sexual discourse - is a conception formulated by Michel Foucault. Sexuality exists predominantly in the discourse, and our culture is one of confession. Finally, the level of the game of power signifies the dialectic game described by, e.g. Slavoj Žižek Love does not entail reciprocation — the desire of something unattainable, in other words, the subjectivity of the other. It functions in accordance with a matrix formulated during the thirteenth century as “courtly love”, which claimed that the Lady was not to be a partner, but a radical Otherness; she was an Alien with whom it was simply impossible to enter into an empathic relation. This matrix proved to be extremely durable, and we encounter it in much later literature and the cinema. | ||

| Anna Burzyńska-Kamieniecka | In Search of Ideal Love. On the Virtual Recipient of Matrimonial Announcements in the Press  | 146 |

The author analysed matrimonial announcements placed by women in the national matrimonial-social life monthly “Kontakt” from February to May 2002, in order to reconstruct the image of the ideal partner and union. The virtual recipient is ascribed concrete desirable features, which indubitably testify to profound pragmatism. On the other hand, the same texts contain conventional expressions referring to stereotype imagery which identifies the beloved with a hero, a fairy-tale prince. The ensuing impression could suggest that the model of ideal love is close to the concept of romantic love. Nonetheless, such an assumption is negated by the very set of traits of the potential partner, precisely selected from the viewpoint of utmost usefulness, camouflaged by means of conventional stylistic measures. | ||

| Agata Jakubowska | Mirror, Mirror on the Wall...  | 149 |

The presented reflections concern two current aspects of gazing into a mirror — the negative and (by referring to publications by Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray) the affirmative side of a relation with one's own image. In the visual arts the act of seeing oneself in a mirror is frequently regarded as an allegory of vanitas as well as a motif that permits viewing the naked female body. The process of looking into a mirror, conceived as an act serving man, is regarded by the feminists as proof of subjecting oneself to the terror of beauty obligatory in patriarchal society. Today, the emphasis placed by the woman on her beauty is frequently treated as a certain strategy, which is by no means a symptom of objectifying oneself, but as a game, a pose, and an attempt at regaining that space of the discourse in which the woman is exploited. The author also analyses the problem of narcisstic love. According to Kristeva, there is hope for Narcissus. She has in mind such a self-love of the woman in which the image is not rendered a fetish, nor is the mirror expected to provide confirmation. It does not answer the question concerning one's own nature, but makes it possible to “become oneself” without halting the creation of identity. | ||

| *** | ||

| Włodzimierz Lengauer | Eros, Polis, the Citizen  | 153 |

The approach to homosexuality in the culture and mores of the ancient Greeks was, as a rule, rather one-sided. Emphasis was placed on the educational aspect of the Greek paiderasteia, frequently perceived as behaviour totally different from modern homosexuality. Meanwhile, while writing about aphrodision chresis Aristotle (Historia animalium 581 b 11? 18) treated all symptoms of sexuality nascent during puberty among girls and boys on par, although in the case of young males he mentioned an inclination towards both sexes. Other traces too (the myth recounted by Aristophanes in Plato's Feast and depictions on vases) distinctly indicate familiarity with, and acceptance of sexual inclinations towards representatives of the same sex on the part of both young boys and mature men. Approval was expressed not only for relations between boys and adults who introduced them to social life, but also among peers. The same criteria of assessment were applied to erotic life as a whole, encompassing relations with the opposite or same gender. Bilateral emotional involvement was regarded as an indispensable element of aphrodisia, supported by physical desire (erotike eunoia); at the same time, every form of erotic relationships was required to preserve decency and remain concurrent with the model of a respectable citizen. The erotic domain, therefore, belonged to behaviour important from the viewpoint of the polis and was considered part of public life (ta demosia), and not intimate privacy (ta idia). The morality and decency of a given citizen (sophrosyne) were evidenced equally by his relations with women and members of the same sex. | ||

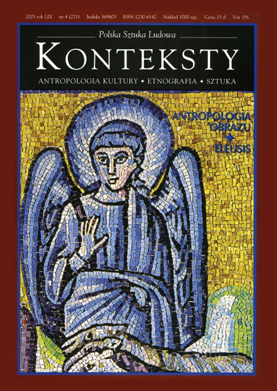

| Filip Taranienko | Wisdom in Eurypides Bacchae: Tragedy as an Initiation  | 162 |

The author of the article analyses notions of wisdom and form in Eurypides' Bacchae. The analysis of the most important appearances of these notions is based firstly on a general vision of the whole play that allows him to recognize its internal coherence and secondly on individual consideration of each analysed character's aspirations. Religious context of the original historical performance is strongly accented. Although a detailed philological analysis of several passages of the play would allow one to view it as a text by itself, the author of the article sees it rather as a historical reality religious and ceremonial in nature. Thus, the play is understood as a series of human attempts to approach the divine and of divine responses to them (as in the famous, frequently criticised, Eurypides' deus ex machina scene). Such an understanding allows the author to argue for a connection between the notions of divinity, form and wisdom, as they appear in the play. | ||

| *** | ||

| Małgorzata Baranowska | The Non-ideal Collection 4. The Postcard and Truth  | 171 |

In these times of mega-scale qualities we never know when we are seeing a copy; art collectors are interested primarily in the original. Since the postcard is copied on a mass scale and inexpensive, the problem of “truth” and “the original” becomes particularly prominent. In a successive installment of her Non-ideal Collection the author writes exclusively about the photographic postcard in an attempt at interpreting it in the categories of the truth of the postcard universe. Not without reason, however, does the postcard belong to those mass media which we may frequently suspect of a rather “casual relation towards historical truth”. | ||

| Agnieszka Kłos | Lomographers Do Not Measure Time  | 179 |

Why the lomographers like to use the lomo (small and old Soviet espionage photo camera)? For some it denotes the registration of fleeting moments, and for others - a cautious attitude towards the world. Lomographers are amateurs of uncontrolled photography. This is the first text on the lomo phenomenon to appear in a Polish periodical. The author analyses not only a group of lomographers, but also presents the new fashion against the background of the history of photography and the world movement. Technical data and facts are entwined with anecdotes and sociological observation. | ||

| Marta Leśniakowska | The Female Modernist in the Kitchen. Barbara Brukalska, Grete Schütte-Lihotzky and ,,Kitchen Themes"  | 189 |

A gender approach to the avant-garde kitchen. The author proposes a new interpretation (deconstruction) of avant-garde architecture and a disclosure of its actual strategies, hidden under the slogans of modernistic universalism. At the same time, the text annuls traditional interpretations of the avant-garde which function as a canon in heretofore literature on the subject, especially in Poland. The presented reflections deal with model kitchens designed by female architects: the German Margarete (Grete) Schütte-Lihotzky (the so-called Frankfurt kitchen, 1927) and the Pole Barbara Brukalska (the so-called Polish kitchen or the WSM /Warsaw Housing Cooperative/ kitchen, 1927). The author discusses the destruction of the traditional space of the home conceived as binary space, indelible in Western culture starting with the modern epoch (the representative zone versus the privacy, domesticity zone). From the anthropological-cultural viewpoint this is a model example of a socio-ethnological orbis interior-orbis exterior division. In a system guaranteeing the retention of the order of the world, based on a Thomist hierarchy of values, the kitchen was “the other”, concealed zone, and as such it is in Western culture a figure of that which is unambiguous, non-ethical, devious and tawdry. When thanks to modernism the kitchen, together with its semantic messages, became a “new stage”, the margin was shifted to the centre, thus relegating the heretofore centre to the periphery and changing traditional spatial/stratification relations. Subsequently, this approach was rendered radical by the art of postmodernism (everyday household activity became the “theme” of a new perception and registration of reality in the form of “dayafterdayism”, a record kept on a “day after day” basis) and feminist art. | ||

| Aleksandra Łukasiewicz | Cloakroom  | 203 |

An attempted examination, conducted from a new perspective, of the cloakroom, a place familiar to all. What does the priest in the sacristy, the ballet dancer in the dressing room, and the actor in the wardrobe share with us, in the act of handing over our coats to the cloakroom attendant? Apparently, this common element consists of a certain suspension between two spheres, the undefined nature of our status. Based on examples taken from daily life and literature the article brings the reader closer to the specificity of this special place. | ||

| Aleksander Jackowski | Budlewo  | 209 |

How are folk culture and tradition to be preserved? Is this task possible? The author describes his visit in the village of Budlewo in the Podlasie region, where an intelligentsia husband and wife team is embarking upon this difficult attempt with love and expertise. | ||

| Agnieszka Tomaszczuk | The Floral Carpet and Its Role in the Life of Parishioners. On the Celebration of Corpus Christi in Spycimierz  | 213 |

In Spycimierz, a small village near Uniejów, Corpus Christi is not only a religious and family holiday, but also an unusual event for the whole parish; its extreme importance lies in the fact that all the parishioners join in a certain task and become involved in a joint endeavour. An important part of the local custom are the preparations for the Corpus Christi Holy Mass and procession, which consist of creating a fantastic carpet composed of the bountiful gifts of Nature. The author presents a detailed description of the creation of the floral carpet, its appearance, and social significance. | ||

| Marta Miskowiec, Monika Kozień-Świca | Homeatmosphere. Between Image and Reality  | 221 |

A description of an art project to take place in Cracow in 2004, involving exhibitions, art campaigns and meetings. The name of the project originates from a popular expression which seems to reflect the balance which the authors wish to maintain between the universal comprehension of the ideal home and the diversity of particular images and experiences. | ||

| *** | ||

| Sławomir Sikora | 229 | |

| Eleonora Tabaczyńska | 232 | |

| Lech Mróz | 233 | |

| Roman Tubaja | 235 | |

| Michał Klinger | Eternal Memory  | 237 |

Reflections on the previous issue of “Konteksty” devoted to Memory and Oblivion, with particular attention paid to poems by Julia Hartwig, which M. Klinger supplements with a theological commentary. | ||